Gertrude Bass Warner (1863-1951)

Collecting Asian Art

Gertrude Bass Warner, the founder of the Art Museum of the University of Oregon (today known as the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art), envisioned the museum as an academic institution that would inspire its audience to learn about Asia through art and stimulate intercultural exchange with the objective of creating a mutual understanding between people and nations. She was convinced that only the mutual respect for cultural values, religious practices, and ethical concerns could eventually rid the world of war. Her motivation was strong because she had seen the devastation left by revolution and war in China, and so she set out on a personal path of improvement: she built an art museum with a mission of educating university students and the public in cultural appreciation and tolerance.

Early life

When Gertrude Bass was born in Chicago in 1863, no one would have guessed that she would become the director and major benefactor of a west-coast university art museum. Her wealthy parents, Clara Foster (1844-1933) and Perkins Bass (1827-1899), doted on their children and thoughtfully exposed them to different cultures through travel and periods of living abroad. Beyond providing a formal education they honed their children’s sensibilities for art, beauty, and different kinds of lifestyles from an early age. And they supported their daughter as much as their sons. Gertrude spent time at a boarding school in Paris, and went on to study art and photography at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. She had taken to photography as a teenager with the support of her family, who set up a darkroom for her in mother’s family estate in Peterborough, New Hampshire.

Gertrude’s philanthropic mind may have received inspiration from her grandmother Nancy Smith Foster, who advocated for women’s education and had financed the construction of the first women’s dormitory at the University of Chicago. In 1920, Gertrude’s mother dedicated a building in her hometown to the Peterborough Historical Society to preserve the history of the area for posterity.[1]

After graduating from Vassar, Gertrude returned to Chicago where she met George F. Fiske, whom she married in 1888. Soon the couple had three children, sons Samuel Perkins Fiske (b. 1889) and George Foster Fiske Jr. (b. 1890), and a daughter, Clara (b. 1893), who died before her first birthday. In 1895 the Fiskes divorced. Gertrude took custody of the elder son, Sam, with whom she remained close for the rest of her life. Sam would be supportive of his mother’s museum project, at times stepping up with cash infusions, when during the Great Depression years Gertrude and the museum had wants of the very basics. She grew estranged from George, who was brought up by his father. After the divorce, Gertrude and Sam left Chicago and moved to the family home in Peterborough, NH.

Gertrude’s further biography reflects her position in the social context of the time. Divorce was not unheard of in Chicago social circles, but a stigma of scandal was attached to the divorcée, and so Gertrude was encouraged by her family to return to the family estate in Peterborough, New Hampshire, until public interest subsided and the scandal faded.

Gertrude Bass turned this situation to her advantage. Her courage and wealth provided the foundation for her later achievements. Her attraction to art and foreign culture—and the inspiration of her brother John Foster Bass (1866-1931),[2] who after building a successful career as a journalist had become a seasoned war correspondent for various prominent U.S. newspapers and journals—motivated her to take her next step. One may speculate that she might never have advanced as she did, had she not gone through the divorce and stepped back from her busy social life in Chicago.

Life in China

In 1904, when Sam was nine years old, Gertrude accompanied her brother to Japan, where he went to cover the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) as a correspondent. In the following year Gertrude left for Shanghai, which John deemed safer for her and her son. He introduced her to his friend Major Murray Warner (1869-1920), an engineer of the American Trading Company, who as a lieutenant of the Shanghai Volunteers had protected American citizens during China’s Boxer Rebellion against the foreign imperial powers in 1900.[3] In the same year, Gertrude and Murray got married. A year later, Gertrude had her household effects sent to Shanghai, where the family lived until 1909.

While in China (and during multiple return trips in the 1910s and 1920s), Gertrude traveled extensively in Asia, exploring China, Korea, Japan, Cambodia, and India—in the company of her husband and, after his untimely death, in the company of American artists Maude Kerns, Elisabeth Keith and Helen Hyde (see interactive map above).

Gertrude documented her travels in diaries and photographs, many of which she took herself, though she also bought photos that she later had made into colored lantern slides. In addition, she and her husband collected reference books on local history, religion, customs, and art, enhancing the collection that Murray had begun before they met.[4] “As a wealthy member of the international community, she was active in the social life of Shanghai, and her entries in her copy of the Ladies Social Register note daily gatherings for tiffin and lunch. Upper-class expatriates did not generally mix with lower class Asians, but Murray Warner made a point of commuting in the third-class Chinese coaches, instead of in the first-class transportation reserved for foreigners, in private protest against exclusionist policies.”[5] Gertrude’s photography collection reveals her observant eye, well trained by the study of photography. She was captivated by her surroundings and inspired to learn about “Chinese customs, manners, etiquette, religion and art assiduously.”[6]

While attracted by art, Gertrude also developed a keen interest in the social conditions she encountered in Chinese and Japanese cities and in the work of farmers in the countryside, as well as women’s work in sericulture. Silk fascinated her beyond the admiration of the exquisite textiles she included in her collection. The production of silk from the unassuming, labor intensive (and smelly) rearing of silkworms through the creation of the elegant fabrics inspired her to rear silkworms in her Shanghai home. That sericulture had been conceptualized since time immemorial as a labor practice predominantly performed by women contributed to her fascination. It is therefore not surprising that her photography collection includes images of textile production she observed during her travels and that her textile collection includes precious robes as well as humble sleeve bands (which were often damaged and could be replaced, while the main body of the garment remained intact). She had no respect for many fellow foreign collectors who only craved objects of exotic beauty, but did not give much thought to the reasons that had led to the devastation of the local population surrounding them: “I have no patience with people who set out on their adventures, determined to live as nearly as possible just as they do at home, stopping at hotels that strive to reproduce all the comforts and luxuries they could find in their own countries, and seeing and learning nothing whatsoever of the real life of the people they are among.”[7]

Beginnings of a museum

In December 1909, the Warners returned to the United States, where they took up residence in San Francisco. During World War I, Murray Warner served as consulting engineer and quartermaster at Camp Dix in New Jersey, which was established in 1917 as a training camp for the 78th Division of the National Army. Two years after the end of the war, on October 2, 1920, Murray Warner died of a stroke at the age of 51 in San Francisco. Newly widowed, 57-year-old Gertrude again had to redefine the direction of her life. She left California and moved to Eugene, where her son Sam had become a professor in the Law School at the University of Oregon. As she became familiar with the university, she decided to give the Asian art collection she had created with her husband a new purpose. In the spring of 1922 Gertrude convinced University of Oregon president Prince Lucien Campbell to build a museum for her Asian art collection, which she would donate in her late husband’s name and enhance with further acquisitions to create an educational resource. The mission of the new museum was summarized as follows: “Illustrating the customs, costumes and manners of the Chinese and Japanese people, their literature, philosophy, religion, arts and crafts, the Murray Warner art collection of the University of Oregon was founded for the purpose of aiding as far as possible the prevention of war between the far east and the Occident.”[8] President Campbell supported the plan, and on November 23, 1923, the collection was formally presented to the public in three exhibition halls in the Women’s Building (today known as Gerlinger Hall). In 1925 Gertrude Bass Warner was formally appointed as the museum’s first director, in accordance with the statutes that define in paragraph five: “It is hereby understood and agreed that during my lifetime I, Gertrude Bass Warner, shall have personal supervision and control over this collection, and be director of same, unless I delegate that office to another of my appointing, subject to the approval of the President of the University of Oregon.”[9]

It would take another decade to raise the funds to build the museum in the center of campus. Designed by architect Ellis F. Lawrence, it opened its doors to the public on June 10, 1933. In her opening speech on that day, Gertrude Bass Warner summarized the evolution of the collection and reminisced about the role her father had played in her childhood, five years of which she spent in France and traveling through Europe, “instilling in us the love of the good and the love for the beautiful, the understanding of which makes the whole world kin.”[10] Comparing the focus of her own upbringing with observations of the behavior of the students on campus, she voiced a deep concern in unmistakable words: “I found the students not at all internationally minded, not at all interested in giving the foreign students a happy time, not at all appreciative because these students had chosen to come to the United States, to the State of Oregon, and to the University of Oregon to get their education and to form their friendships. So I went to work to see what could be done to change this situation, and to arouse in our students some understanding of the brotherhood of man, all children of one Father.”[11] Her Christian conviction shines through her words, a faith she shared with many of the adventurers, travelers, missionaries, and others of the community of international expatriates she had encountered in Asia, including two of the collectors who became instrumental in helping her enhance her collection significantly with quality pieces: the missionary-turned-educator and adviser to the Chinese government, John Calvin Ferguson (1866-1945) and the Norwegian Johan Normann Munthe (1864-1935), who had served as a general in the Chinese army and was, like Warner, a member of the Christian Science community.[12]

Building a collection

The affiliations of expatriates in China had as many facets as faces. Some sought adventure in turmoil, others represented their governments, companies, and/or religious communities in search of a role in the New China that would emerge after the demise of imperial rule. Yet others hunted only for economic profit. Their entrepreneurial spirit was often matched by their conviction of the superiority of their Christian faith and their race, which led many expatriates to display arrogant ignorance about their host countries’ culture while actively exploiting the precarious conditions of the local population.

Times were difficult in China in the 1920s, when warlords competed for territorial supremacy and social and political order were fragile and volatile. Under these circumstances the market for high-quality antiquities and works of art was fed by the despair of many who sold their heirlooms in order to survive or to move out of contested areas. Gertrude Bass Warner was aware that her idea of building a museum with Asian objects to educate her countrymen benefited from the despair and uncertainty that motivated Chinese collectors to sell their precious possessions. Palace objects were sold by eunuchs who no longer had a professional function and whose services would never again be in demand. Since they commonly did not have a family to turn to, to secure their survival they tried to maximize their profit by selling objects stolen from the imperial household or palace storage. Warner recognized that the political turmoil in China made possible art acquisitions that under peaceful circumstances would have been out of the question: “The chaotic condition brought curios onto the market that would otherwise not have been disposed of, and there being very little competition, the price was considerably lower than [if they] would have been obtained in a time of peace.”[13]

Once she had made acquisitions for the museum, she tried to make sure to the extent of her possibilities that the pieces reached their destination. In one particular case this took special courage. During a visit to Beijing in November 1924, Warner left the city on the International Train, that connected the capital with the port city Tianjin. The battle for Beijing between the armies of competing warlords, attacking General Zhang Zuolin (1875-1928) and capital defender, General Feng Yuxiang (1882-1948) made staying in Beijing dangerous. While the train crossed contested territory, the locomotive was destroyed. The train stopped for hours until a new locomotive could be attached. Most passengers left the train to seek refuge in a nearby town, yet Gertrude Bass Warner stayed on the train protecting the art work that was to be shipped to Eugene from Tianjin. She recorded her experience while waiting for help in a letter (below) that reflects the danger of the situation.

Guided by both her admiration for the refinement of Asian arts and cultures and a compassionate and philanthropic mind, she contributed in her own way to the visual accessibility of Asia—for students at the University of Oregon and the public in the Pacific Northwest. Her collection intended to teach about the history, material culture, and aesthetic principles of Asian cultures whose members the American public so far had either observed in the role of hardworking foreigners performing menial tasks with whom the average white Americans did not socialize, or as participants and victims of revolutions and devastating wars fought across the Pacific. Warner’s sojourn in (and multiple return trips to) Asia shaped her subsequent life in the United States. After the early death of her second husband, Warner’s Asian experiences gave her a mission and social respect she would otherwise would not have enjoyed as a widow without professional purpose.

As much as Gertrude Bass Warner had shaped the plans for the museum, the museum now came to shape her life. She studied best practices for a well-maintained museum and considered every aspect of operations. She traveled to museums with Asian art in Seattle, San Francisco, Boston, New York and Washington, D.C., to learn from established models: the correct storage of artworks in accordance with the requirements of their respective materials, the writing of labels for display in exhibitions, the organizational structure of the museum, the handling of art, from packing, transportation and filing customs declarations to accession practices, and the optimal, safe installation of objects to make them visible to visitors. Light-sensitive materials like textiles and works on paper demanded minimal light exposure, and therefore the large windows with which Ellis Lawrence had planned to adorn the museum façade to let in natural light were removed in favor of indirect lighting.[14]

On June 27, 1929, Warner reported to her friend John Ferguson about her the previous months’ activities to advance the museum project. She had traveled to Los Angeles, Chicago and Philadelphia, where she attended a museum conference. She ranked the building of the Philadelphia Museum higher than that of the Metropolitan Museum: “They have a wonderful new museum here, the Philadelphia Museum, and I think the building is better adapted to the modern idea of a museum than the Metropolitan which has had addition put on it from time to time, which, in my opinion is never so good as the larger idea to start with. They are going to have rooms for the different countries, one after another, starting from the Mediterranean going along down the line from country to country till they reached China and Japan.”[15] In her description we see her witness the development of the ideal of chronologically narrated, usually geography-based installations, which today seems to have reached the limits of its original purpose.[16]

In the same letter, Warner mentions that she received an honorary Master of Arts degree in Public Service during the Commencement ceremony of June 1929 and acknowledges the role that Ferguson’s support for her museum had played in this achievement: “Returning to New York I received an invitation from President Hall of the University of Oregon to return to the University in time for Commencement to receive an honorary degree—Master of Arts in Public Service. To you who have received all kinds of honors from all over the world, this will not seem to be much, but to me it is the first recognition of my public service and in receiving it I did not forget the kind, true friend who has done so much towards bringing it about.”[17] The honorary degree was given "in recognition of her scholarly contribution to a better understanding of the art and civilization of Oriental peoples through her discriminating selection and organization of material contained in the Murray Warner Collection, and her tireless efforts in the promotion of international goodwill.”

Until the end of her life Gertrude Bass Warner managed and expanded the art collection at the museum. She also supported the establishment of an Asian Studies Program at the University of Oregon and established a state-wide essay contest for students on topics concerning Asian culture. After her son Sam Bass Warner eventually left the University of Oregon, first to teach at Syracuse, then at Harvard, his mother continued her support for the art museum and alternatingly lived in Peterborough, NH, and taking residence in hotels in Eugene, Chicago, and in Arizona where she cared for her mother, Clara Foster Bass, until she passed away in 1933. In multiple ways this must not have been easy: as we learn from a letter Normann Munthe wrote to Warner on June 25, 1930, she had been ill with pneumonia, which he took to heart, commenting: “Is it, I wonder that we are paying up for our sins in former existences? I can find no other explanation.” In addition, Clara Foster must not have been a patient person to care for. Munthe responds to a remark Gertrude must have made in a letter to him, bemoaning the fact that she failed her mother’s expectations with the following comment, that once again references their shared faith in God: “I make what you say about your mother; yes, dear Friend, it is very, very hard to be found fault with, when one tries one’s best to please, but bear in mind that she is nearly blind, as you say, and also bear in mind that we are never sorry for having been too kind and confiding, even if we are taken in from time to time. It is better to be too kind than the reverse. God is Love, and we must try to reflect it as much as we can, and I know no person who is keener alone to kindness than what you are, nor do I know of anyone, who shows in her acts that she is kind and thoughtful than what you do. I take my hat off for you and consider your friendship a gift from God—all sunshine and now shadows.”[18]

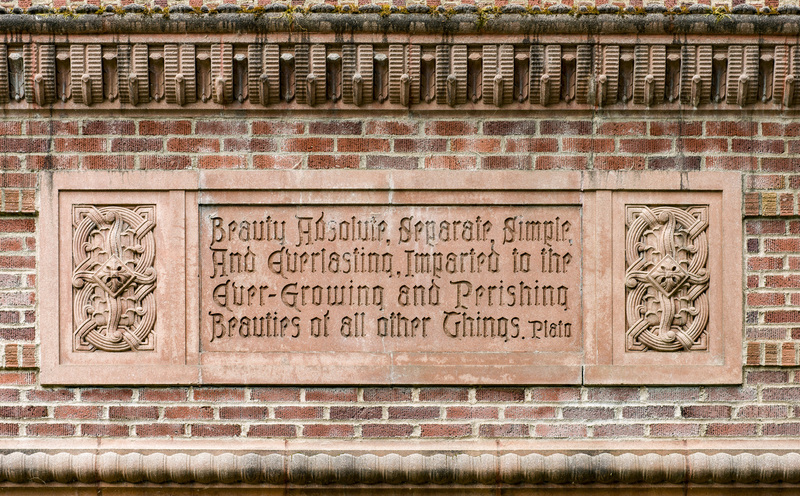

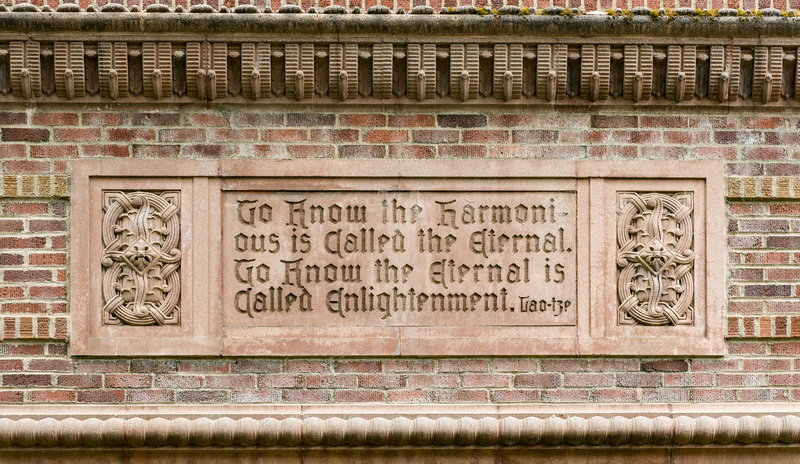

Gertrude Bass Warner remained dedicated to the idea that art connected people and nations beyond borders. In this spirit she supported the United Nations, and held memberships in several organizations that furthered her involvement in networks that supported her educational museum, among them the Institute of Pacific Relations, the Meiji Japan Society, the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Association of Museums, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the American Federation of Arts. She saw herself as a facilitator for an improved understanding between West and East, a vision that is reflected in the short quotes from Plato[19] and the Chinese classic Daodejing (attributed to Laozi)[20] that can be seen on the south facade right and left of the museum entrance.

A lasting legacy

In addition to her work at the University of Oregon, Gertrude Bass Warner also established museums at St. Mary's Hall[21] and at the International Institute,[22] both located in Shanghai. She provided scholarship assistance to students from Asia, including funding for the University of Oregon’s first female full-time student from Japan, Nakajima Takako, from 1935 to 1937.[23] The museum that Warner created and that to this day remains a multi-faceted laboratory of learning continues to surprise, challenge and inspire its visitors, although it has not received the funding and public support it deserves as the largest and most active academic art museum in the state of Oregon. It seems that few among the university’s many presidents over the years understood the significance of the museum as an incubator of thought. Until her death in the family home in Peterborough, NH, in 1951, Warner, who had invested a fortune into the art collection, had to beg the university administration for basic supplies: “The museum needs a type writer. —We also need a vacuum cleaner and a slide projector.”[24]

While its focus on Asian art and art of the Pacific Northwest is still at the core, the museum has expanded beyond the encyclopedic survey evolved from eighteenth-century royal collections and institutions that shaped the definition of culture in the modern nation state. It supports the university’s mission as “a cosmopolitan institution that transcends national identities, promotes tolerance, and a shared sense of history among diverse cultures of the world.”[25] In an age of mass culture and attempts to objectify it as an instrument of market capitalism, the teaching museum envisioned by Gertrude Bass Warner still stands its ground.

As such, it deserves respect and support.

References

[1] According to Gertrude Bass Warner, the building contained “a museum of Colonial art [and] a museum library for books on New Hampshire.” (Speech given by Gertrude Bass Warner at the Opening of the Murray Warner Collection of Oriental Art on June 10, 1933. Oregana 1934, 161). A plaque at the entrance remembers Clara Foster: “A resident of Peterborough, a lover of her neighbor and her State, she dedicated this building to house records of The History of this town and of The Monadnock Region To preserve memorials to the sons and daughters of Peterborough and to provide a meeting place for The intellectual and social advancement of future generations”. The building is used by the Peterborough Women’s Club. https://peterborough.oncell.com/en/clara-foster-bass-plaque-53248.html, accessed 5/29/2019.

[2] John Foster Bass was a war correspondent who had—as the only U.S. war correspondent—covered the Egyptian-Sudan campaign of 1894. He later reported about the Spanish-American War for the New York Evening Post and about the subsequent U.S. campaigns in the Philippines for the New York Journal. He covered the Boxer Rebellion in Shanghai in 1900 and one year later went to St. Petersburg for the Chicago Daily News, where he stayed until 1915. He covered World War I at different locations in Europe and was wounded in 1916 while reporting from the Russian front. He also reported about the proceedings at the 1919 Peace Conference in Versailles. (Mitchel P. Roth, James Stuart Olson, Historical Dictionary of War Journalism. Greenwood Publ. Group 1997, 24. https://books.google.com/books?id=Og85_oqumYC&pg=PA24&lpg=PA24&dq=Historical+Dictionary+of+War+Journalism+john+bass&hl=en#v=onepage&q=Historical%20Dictionary%20of%20War%20Journalism%20john%20bass&f=false, accessed 5/25/2019.

[3] At the time John had covered the rebellion as a reporter, but Murray and John may have first met earlier, during the Spanish-American War in the Philippines.

[4] These materials are now at the University of Oregon Libraries, Special Collections and University Archives (SCUA), and at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum or Art (formerly the University of Oregon Art Museum).

[6] Gertrude Bass Warner, “Friendly Relations,” address given by Warner in 1924. https://oregondigital.org/catalog/oregondigital:df71jp11k#page/3/mode/1up accessed 06/02/2019.

[7] Gertrude Bass Warner, “Foreword,” in When West Meets East. 1921. Unpublished manuscript. Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries.

[8] Preface of Oregana 1924. The yearbook was dedicated to Gertrude Bass Warner in honor of the donation of her collection: “To a Woman of Large Heart, Farsighted Purposes, and Abounding Generosity” (Eugene: The Associated Students).

[9] Oregana 1934, 166.

[10] Oregana 1934, 161.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Christian Science is a religious movement that originated in the 19th century in New England based on the writings by Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910). The sect quickly attracted members all over the world. It is probably best known for its globally available newspaper, the Christian Science Monitor, which received seven Pulitzer Prizes between 1950 and 2002. Public Reading Rooms of the Christian Science Monitor can be found in many countries.

[13] Gertrude Bass Warner speech given in 1924, titled ‘Friendly Relations’, 2. https://oregondigital.org/catalog/oregondigital:df71jp11k#page/3/mode/1up accessed 06/02/2019.

[14] The windows were the built into the University Library building, also designed by Ellis Lawrence.

[16] Sonya S. Lee, “Introduction: Ideas of Asia in the Museum,” Journal of the History of Collections, vol. 28 no. 3 (2016), 359-366.

[19] “Beauty—Absolute, Separate, Simple and Everlasting, Imparted to the Ever-Growing and Perishing Beauties of all Other Things.” Plato

[20] “To Know the Harmonious is Called the Eternal. To Know the Eternal is Called Enlightenment.” Laozi

[21] Between 1881 and 1951, St. Mary's Girls' Middle School was one of the top institutes of education for young girls from wealthy, predominantly Christian families. http://app1.chinadaily.com.cn/star/2001/0426/cu18-2.html accessed 5/25/2019.

[22] The International Institute had been founded in 1894 by Gilbert H. Reid (1857-) a Presbyterian missionary, as “a perpetual Congress of Religions.” http://www.studiesincomparativereligion.com/public/articles/The_International_Institute_of_Shanghai_an_Eastern_Parliament_of_Religions.aspx accessed 5/25/2019.

[23] Larry Fong, “The Collector”, in David A. Robertson (ed.), Precious Cargo: The Legacy of Gertrude Bass Warner. Eugene: University of Oregon Museum of Art, 1997, 21.

[24] Haakestad (2018), 164.

[25] Lee (2016), 361, refers to the contribution by James Cuno in the same volume.