Frederick Starr and the 1904 World's Fair

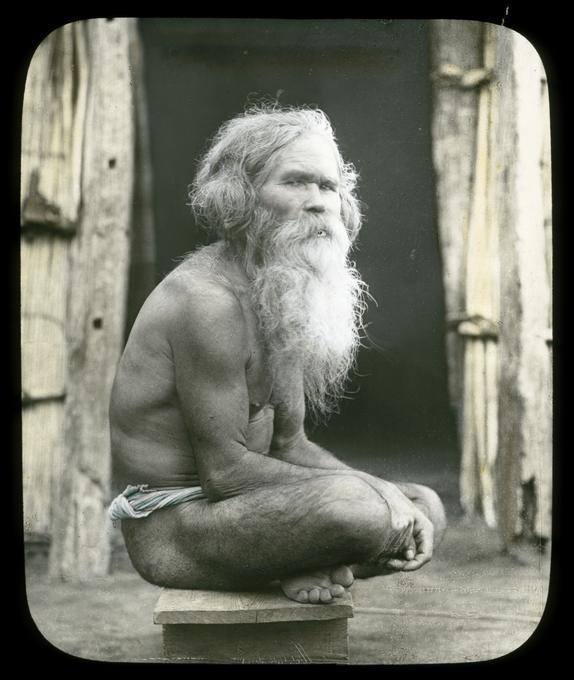

In 1903, Frederick Starr, an American anthropologist working at the University of Chicago, was asked by his friend W. J. McGee (1853-1912) to curate an exhibition for the upcoming 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. At the turn of the last century, many American and European anthropologists had a keen interest in the Ainu, who they (incorrectly) believed to be an ancient Caucasian people now colonized by Japan. Despite this intense academic interest, however, few Westerners actually had the opportunity to study and engage with Ainu communities firsthand, and feeling an Ainu exhibition would make an excellent addition to the World’s Fair, Starr eagerly agreed and quickly departed for Japan.

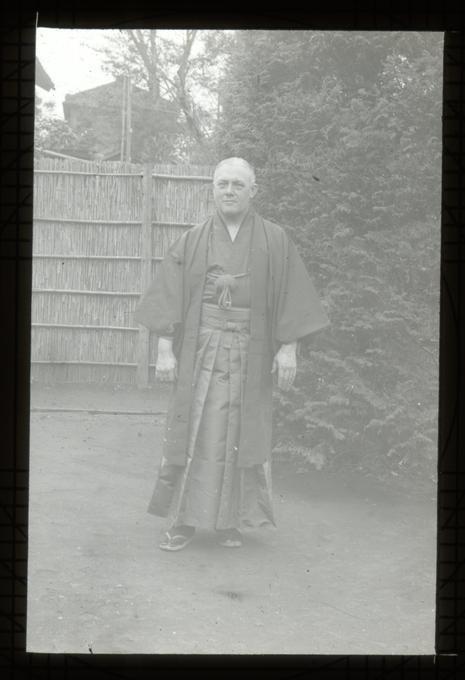

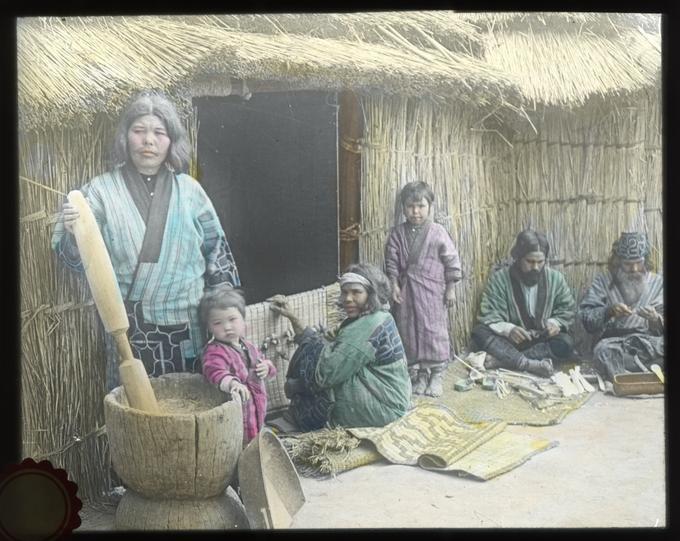

When Starr arrived in Japan in early 1904, he found the country was deeply entrenched in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), making his journey northward extremely difficult. Nevertheless, with the help of Rev. John Batchelor (1855-1944)—a British missionary living in Hokkaido who not only wrote numerous books on Ainu culture but also served as a key contact for other writers, like Isabella Bird (1831-1904), Arnold Landor (1865-1924), and Elizabeth Keith—Starr traveled to Biratori, where he took copious notes on Ainu customs, traditions, and life. After canvasing many villages in the area, Starr procured a traditional Ainu house (cise), storage shed, and many other cultural objects and artifacts, and even met nine volunteers who agreed to travel to St. Louis and participate in the exposition.1

The 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair proved extremely popular, generating even greater interest in the Ainu among American and international audiences. However, despite the great fanfare of the Ainu exhibition, today the legacy of Starr's involvement at the World’s Fair remains complicated. On the one hand, during his travels Starr amassed an extensive collection of art, photographs, and other objects which have been integral to Ainu scholarship in the United States. Even today, Starr’s original acquisitions make up a significant part of the Ainu-related materials in the U.S., and his collection has since been dispersed among many American museums and universities—including the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Logan Museum of Anthropology at Beloit College, and the University of Oregon’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art.2 On the other hand, however, much of Starr’s behavior in Hokkaido would be considered extremely offensive by contemporary standards, and the anthropological exhibitions at the World’s Fair, which have been described by many as “human zoos,” have been justly criticized. The handling of the entire affair ignores the humanity, agency, and voices of the indigenous participants, whose experiences are rarely, if ever, discussed. While not much is known about what happened to Sangyea, Santukno, Kin, Kutoroge, Shutratek, Kiko, Yaso, Shirake, and Bete Goro (the nine Ainu individuals who took part in the 1904 World’s Fair) after the event, it is important to recognize and remember them.3

1.) Donald McVicker, Donald. Frederick Starr: Popularizer of Anthropology, Public Intellectual, and Genuine Eccentric (Lanham, M.D.: AltaMira, 2012): 89.

2.) Yoshinobu Kotani “Ainu Collections in North America: Documentation Projects and the Frederick Starr Collections,” in Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People, 143.

3.) Frederick Starr, The Ainu Group at the Saint Louis Exposition (Chicago, I.L.: Open Court Publishing, 1904): 77.