Origins and offerings

The practice of pasting senjafuda can be thought of as a specialized variant of the practice of giving offerings to seek blessings or accrue spiritual merit. An offering can be as simple as a few coins tossed into the offertory box found at the threshold of a shrine before praying to the god worshipped there. Or it can be as complicated as copying out an entire Buddhist sutra by hand and presenting it to a temple (a common form of devotion in premodern times). Buildings, icons, and furnishings are commonly presented or funded as offerings, often with the donor or donors identified by name in recognition of their devotion.

One common form of offering is the ema 絵馬, a kind of devotional plaque. Ema literally means “picture horse,” a name that nods to the legendary history of the practice. Anciently, horses were given as gifts to shrines, but then pictures of horses came to be substituted for the real thing; eventually these pictorial offerings came to depict other themes than horses. Ema can take the form of large paintings on wood of religious or historical themes, commissioned by devotees and presented to temples or shrines for display in special buildings. They can also take the form of small wooden plaques with a simple pictorial design unique to each temple or shrine; devotees can buy the ema at the temple or shrine, write a prayer on the back, and hang it at a designated spot on the temple or shrine grounds (or keep the plaque as a souvenir). Ema are a common motif in pictorial senjafuda, perhaps to remind collectors of the larger tradition of votive offerings of which senjafuda are a part. The Starr collection contains senjafuda reproducing large painted ema and many, many slips depicting the smaller ema sold at temples and shrines.

The two senjafuda above depict large painted ema. The one on the left shows the medieval legend of the slaying of the nue. The nue was a chimerical creature (part monkey, part snake, part other animals, depending on the source) that, according to early stories, menaced the Imperial palace until the warrior Minamoto no Yorimasa shot it down with an arrow; his retainer I no Hayata administered the coup de grace with a blade. The next senjafuda shows another medieval legend, that of Ibaraki Dōji, an oni who tangled with warrior hero Watanabe no Tsuna. In their first encounter, Tsuna cut off Ibaraki Dōji’s arm; later the demon visited Tsuna’s house disguised as his aunt and stole back his arm. Both of these senjafuda take the form of large painted ema made for presentation to a temple or shrine, with black lacquer frames with metal ornaments completing the illusion.

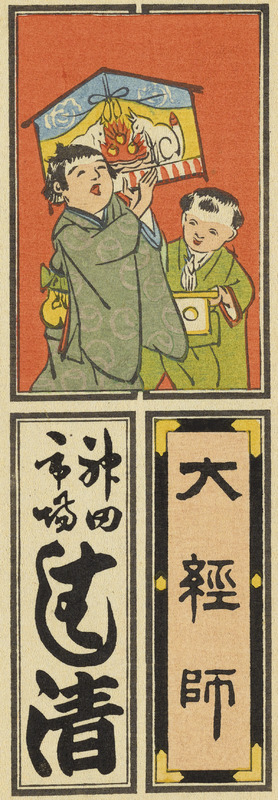

The next three all depict the smaller ema sold at temples and shrines. The first one shows two children, presumably on their way back from a visit to an Inari shrine; the one on the right holds a small fox figurine on a stand, while the one on the left shoulders a wooden plaque with two foxes drawn on it. Incidentally, this is a one-chō senjafuda divided into four quarter-size slips; the top two are occupied by the picture of the children, while the bottom two are devoted to separate daimei, and the one on the bottom right is framed as a large presentational ema would be. The next slip shows an ema belonging to the Kijin Shrine; ema produced by the shrine sport this distinctively sketchy pair of oni. The final slip shows another Kijin ema along with one depicting a sumo match (sumo wrestling also has historical connections with Shintō worship), against a background design of ema shapes.