-

Escape from Peking/three Japanese letters, handwritten notes.

Transcript:

Escape from Peking on Nov. 9, 1924

Admiral Oriental Line

Managing Operators U.S. Shipping Board

SS “President McKinley”

Mrs Boyd Carpenter & I have the stateroom. Mrs Scalia [?] & Mrs Potter are in a section in the open car.

9 A.M.

As we sit here in one car on the train, we not only hear the guns that are fired from Tientsin—we feel the explosion.

Mrs Scalia has started off alone on foot to see if she can get a man at the the railway station to [illegible] our baggage & to try to find out if we can go directly onto our steamer. The station is some miles & a half away. If we would leave the trunks behind we could all walk with her but of course I will not leave the Museum things behind with no one to look after them.

10 A.M.

Before leaving Peking we sent a telegram to the Astor House Hotel in Tientsin asking for rooms. They have sent their porter with an automobile & two assistants to look after the baggage. Leaving the train, as one passed the engine I [illegible] to take another picture of it. There were some British soldiers nearby. I asked them to come close that they could be included in the picture. All the British soldiers still guarding the train, came. Having taken the picture & thanks them for their faithfulness & protection we went on our way rejoicing. We had come the 80 miles in 31 ½ hours. No one had been hurt.

In the office of the American Express Co. we found Mrs Scalia. She reached the railway & train just as Marshal Wu [Wu Peifu of the Zhili Clique] with some 600 of his followers were leaving by train for the coast, there to take a ship for Tsingtau [Tsingtao/Qingdao]. His army was left in the lurch, no food, no shelter, no money & and most of them are a long way from home. With everything to lose & nothing to gain how can they be induced to join the army?

And speaking of fighting, one of Marshal Wu’s officers did refuse to fight. He was decapitated there in the station just as Mrs Scalia arrived. His head was placed on a spike for all to gaze upon. It was pandemonium let loose, in that station, and a body blow to my siding with the Wu faction. It reminds me of midaeval [sic] Europe.

Dear old China. This is the 5th revolution in eight years. May it be the last.

----

1

from Peking

Our escape with our treasure for the Univ of Oregon Museum

Indochina S.N. Coy. Ld.

I have written you how difficult it was to reach Peking from Tientsin because Chang So-lin [Chang Tso-lin/Zhang Zuolin of the Fengtian Clique] was moving his army and his supplies—getting ready to attack the government.

We were glad to find room at the Hotel des Wagons Lits because it is in the legation quarter and just across the street is one of the embassies & our American Legation so we could always give the flag just inside the entrance a silent greeting.

While Chang Tso-lin was preparing to attack the government forces, with the object of moving on to Peking, General Feng—the Christian general [Feng Yü-hsiang/Feng Yuxiang]—was given the task of blocking him.

We reached Peking in the midst of the preparations. Automobiles, horses, mules, carts, everything in sight was commandeered, including the men who drove them.

Our rickshaw coolies requested American flags to place on our rickshaws to protect them and us. Every foreigner flew his flag on anything and everything that belonged to him, as a warning to the recruiting officers to keep their hands off.

General Munthe’s guards, the Chinese protection for the Legation Quarter, patrolled the southern [illegible] of the city in groups of five.

When General Feng’s army left, there was a sigh of relief. But about this time the Chinese merchants began to consider what would happen if General Feng’s army should be defeated—and trunks, boxes, baskets—chests of drawers—every conceivable kind of receptacle, was filled with merchandise & taken to the sheltering wings of some foreign friend in the Legation Quarter. Simultaneously the Chinese began to send their women & children to our hotel for refuge.

Our first realization that the supplies were low came when the marmalade—which is a part of every Englishman’s breakfast—gave out, then the butter. Lard was substituted. Also altho the cold weather had set in, our hotel was not heated. We wore our winter coats in our rooms.

Then, two weeks ago, on Nov. 6th, as I sat in the lobby of our hotel waiting for Mrs White—the Princess der Ling—Dr Ferguson came in, “Where are you going” “On an errand outside the city wall with Mrs White” “Don’t you go. The city was capture last night by Feng’s troops. Railroads, telegraph, telephone have been stopped—and the city is guarded in sections so that no one shall get away.” “But General Feng?” I asked. “He has deserted the government and joined forces with Chang-Tso-ling [sic]. Stay in the Legation Quarter.”

He waited until I had promised.

Wem as well as the Chinese—were considering the possibility of Chang-Tso-lin’s soldiers looting the city and were starting to gather in our Museum things to be packed. Mrs. White & I were going to a Chinese tailor in the Chinese city, outside the walls of the Mandarin, or Imperial city, where I had left an imperial coat, brought from collection at home, to be made up. In the case of looting, everything in the shop including that could would be lost.

Mrs White felt that she, a Manchu princess, could go where she liked, & [illegible] into her car. She went a block, as far as the city gate, & was turned back.

We were quite short of funds, & not knowing what might be ahead of us. I went to the International Bank—located in the Legation Quarter—for money.

The Chinese, fearing that the government paper money might become invalid—were making a run on all the banks, demanding silver in the place of their paper money. The Chinese banks promptly closed their doors. In the enclosed section, set-aside for their Chinese depositors in the International Bank, there was a seething mass of people all calling at once to attract the attention of the clerks & get their paper money changed to silver. The young woman who waited on me said they would not have to close their doors, as they had millions in their vaults.

In the meantime, Mrs Scalia & Mrs Potter had taken the bit in their teeth & gone in another direction for the porcelains that I had left with the dealer to be packed. Two [illegible] brought them all back to our hotel. The Legation Quarter is the safest part of the city. It is guarded from the inside by the marines from all the Legations—and from without, so we thought, by Gen. Munthe’s troops. But no, when the city was captured the Chinese guards were incarcerated & only allowed to go out one at a time after swearing allegiance to their captors.

General Feng said he would maintain order & there should be no looting. Two would be looters were promptly decapitated & their heads, each in its box was exposed at the city gate as a warning.

The city was hermetically sealed—no one could go in or out of the city on that day. No [illegible], no telegraphy, no telephone, no mail—it was hermetically sealed except for one means of communication. Our American Legation has a wireless & sent word of our plight to the world.

The President of the Republic was under guard in his palace. One official was locked in the cellar of Gen. Feng’s house, being held for a ransom. The rest of the officials of the old government came into the Legation Quarter, where they were—by treaty—immune. They flocked into the Hotel des Wagons Lits until every available nook & corner was taken. Some of them came down to the dining-room for their meals but most of them, considering discretion the better part of valour, staid in hiding in their rooms. The halls & stairs were crowded with Chinese children, as many girls as boys, I was happy to see.

When, in Tokyo, we talked over the pros and cons of coming to Peking with J. Ballontine [?], our Vice-Consul he said it would be safe to go to Peking, because it would always be possible to get away. According to our treaty the railroad between the Capital & the sea must be kept open.

The diplomatic body was called together. The nationals from each country were carefully [illegible]. There were 1300 Americans who might have to be taken with our Legation if the government side should say to Gen. Feng, “No you don’t,” and there should be a fight in within the city.

After a few days our International train was sent up from Tientsin, with 200 guards, mail & reinforcement of soldiers for the Legations. The train arrived at eight o’clock, started back two hours later. Draped over the front of the engine was “old glory” & on the sides the English, French & Japanese flags.

The train reached Tientsin safely. Once it came up and returned at night, we thought that we would go on the 2nd but Dr Ferguson was opposed. He said “you may get there and again you may be turned back. There is fighting all along the track. If you are turned back you will have lost your places in this hotel in the Legation Quarters. We could take you in, but how about Mrs Scalia & Mrs Potter?”

There is a shortage of fuel and food in Peking. The Fergusons had changed their way of living so that if necessary they could get along with one fire, beside the one in the kitchen. Their coal on hand would only allow that much—(In Peking there are no furnaces, the rooms are heated by little iron stoves.)

General Feng is in league with Soviet Russia. The Soviet government has established itself not in a Legation like the other foreign powers, but in an Embassy, in the Legation Quarter. An ambassador takes precedence over a minister, and the situation is full of possibilities.

The government party did say “No you don’t” to General Feng, & Marshal Wu’s army was started for Peking.

Once General Feng left the city, this time to fight his old chief. We watched the soldiers as they marched out through the city gate. They were singing our hymns.

At this juncture the Belgian Minister was ordered transferred to another post. The International train was again sent from Tientsin to fetch him his wife and their belongings as far as Tientsin.

We decided that presence would be brought to bear to get that [illegible] [illegible] and we would go. It arrived Saturday night at 7:30 and left at 4 A.M. Sunday morning.

To go on the International train it was necessary to go to our Legation, armed with passports, each personally making the request. There should be no question as to who went aboard. We were each given a permit to go on the train. The new government was very much on the alert to see that no members of the old government should get away in disguise.

In order to make sure of our places, we went aboard the night before. Shortly after the train came in.

There was a car for the Belgian Minister, one American car, two British cars, a dining car, a baggage car, and four cars for the guards. The French Capt. Bertrand in command. The cars were not heated. The temperature was considerably below freezing—we could see our breath.

Our trunks being safely in the baggage car, we found Mrs Boyd-Carpenter in the American car. Her husband professor of International law teaches in one of the Universities in Peking. She and I occupied a compartment while Mrs Scalia and Mrs Potter had a section in the open car. It was a 2nd class car. The seats covered with leather, without padding or springs—no sleeping accommodations.

French soldiers both from France and [illegible], Tommie guns in hand, kept going back and forth all the night.

It had been expected that Marshall Wu’s forces would push Gen. Feng’s closer & closer to the city until he would be forced to take refuge inside the city walls. Then when coal & food gave out, the city would surrender.

We went very slowly—a detached engine ahead, with English marines aboard, looking for bombs and derailed tracks.

At 9 A.M. we came to the first trenches. Three long zigzag trenches, some distance apart, running at right angles with our track. There was no sign of life in any of them. That meant that Feng’s forces, that left Peking to fight Marshall Wu, were advancing, not retreating. We crept along. The country was absolutely deserted. At the little stations, a few soldiers and a few camels carrying supplies. Suddenly clack clack clack clack—the advance engine was being fired upon as a notice to stop. A long wait, then a slow advance until fired upon again. The International train was not expected, and the soldiers did not know what to make of the foreign flags flying so independently over the engines.

After a couple of these unpleasant experiences, our engineer, Chinese, refused to get up from his prostrate position & man the engine, but one of our American officers took his place. A fusillade, a long stop. We were informed that there were sand bags on the track ahead. A request from us that they should be removed met the response that if we wished to go forward, we could go with the firing line and remove them ourselves—which our soldiers eventually did.

Feng’s soldiers had red badges with a white disk on the left arm. Long lines of them marching with an encircling movement, in the same direction that we were going, made us think that they were encircling Wu’s forces.

There was a sudden stop. A detached rail ahead. All hands got out to “look see”. The Jonnies pushed it back into place very quickly.

Finally we came to the outposts of Feng’s forces—instead of trenches, round holes with a man or two in each, just their heads and guns showing.

The danger seemed over. The reconnoitering engine was switched off, and we went on a little faster, much relieved.

Not having slept the night before, I was indulging in a nap when suddenly roused by Mrs Potter. “Gertrude they are firing on us with a machine gun.” Bum bum bum bum—it seemed to last a long time, but perhaps it was not more than a couple of minutes. We were ordered onto the floor by the French Commandant. It was Wu’s men. There being no reconnoitering engine ahead of us, the gun was aimed at our engine from the machine gun on the track ahead. The glass in the engine now was broken. The bullets whizzed past our coaches. We were near Tientsin. Marshall Wu’s men had made a quick retreat, Of course they took us for the enemy. They apologized.

Our train was unable to reach the city because of congested tracks. So we spent a second night on the train. Captain Bertrand, with a couple of aids [sic] went for help. He feared that Gen. Feng’s men would follow on the heels of Marshall Wu’s retreating forces & as one of our boys expressed it—“clean us up.”

Many of the soldiers left the train.

The men passengers put their hand baggage on the seats, and walked the mile or so to the station.

We would not leave our baggage—those precious Museum treasures—so the little group of six women and such of the guards as had stood by, spent the night in watchful waiting.

The next morning Mrs Scalia started on foot for the station in search of a [illegible] to carry our baggage.

Mrs Potter & I staid on the train to be with it—I was going to say—to guard it.

Before leaving Peking we had telegraphed to the Astor House Hotel at Tientsin for rooms. About an hour after Mrs Scalia left, who should come asking but the hotel porter & his assistants. The assistants got into the baggage car to stay with the trunks until they could be taken out, while the porter took us to the automobile.

Passing our engine on the way, I stopped to take another picture of it. Nearby were some British soldiers. I asked them to come close so that they would be included in the picture. All the British soldiers still guarding the train came. Having taken the picture & thanked them for their faithfulness & protection we went on our way rejoicing. We had come the 80 miles in 31 ½ hours. Altho shells had passed above & beneath us, no one had been hurt.

At the office of the American Express Co. we found Mrs Scalia. She had reached the railway station just as Marshal Wu with some 600 of his followers were leaving by train for the coast there to take a ship for Tsingtau. His army was left in the lurch—no food—no shelter—no money & most of them a long way from home. With everything to lose & nothing to gain how can they be induced to join the army.

And speaking of fighting—one of Marshal Wu’s officers did refuse to fight. He was decapitated there in the station just as Mrs Scalia arrived. His head was placed on a spike for all to behold. It was pandemonium let loose in that station. And Marshal Wu’s last-act was a body blow to my siding with the Wu faction. It makes me think of the conditions in Medeaval [sic] Europe.

Dear old China. This is her fifth revolution in eight years. Somehow she will find a solution to her problem and settle down in peace. We all hope soon.

Gertrude Bass Warner

Correspondence/diary

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Mrs. Warner's speech at the opening of the Murray Warner Collection of the Museum of Art on June 10th, 1933 (Museum copy)

Transcript:

Museum copy

Mrs Warner’s Speech at the opening of the Murray Warner Collection of the Museum of Art on June 10th,1933.

Members of the Board of Higher Education, Mr Chancellor and Friend, All.

This a very happy occasion for me. We are assembled here today in order that I may present this collection to the University of Oregon as a memorial to my husband, Murray Warner. It is also a tribute to my father, Perkins Bass, who had a wide interest in art and his love for humanity took in everyone who came within his reach, both at home and abroad.

During my childhood we were in Europe for five years and hew was with us much of that time, instilling in us the love of the good and the love for the beautiful, the understanding of which makes the whole world kin. My husband’s interest in art and his love for his fellow man were as deep as that of my father.

In the summer of 1906 I had an experience in Japan which interested me very much. In those days I was doing a great deal of photography and wanted to take pictures of everything. I went with my guide to the famous art museum a Nara and after carefully through the Museum I asked the Director I could take pictures of the status. He looked at me doubtfully and then asked what I wanted to photograph. Due my early training I was able to point out to him the museum’s greatest treasures, making no mistakes and consequently permission to take these pictures was graciously granted, even a step-ladder was provided upon which to place my camera. As I finished, I discovered a beautiful statue twice life size, in a dark corner at my request the Director had it moved to the verando [sic] so that I could photograph it. The pictures taken at this time have been made into colored lantern slides which I greatly prize. When I went to the Director’s office to thank him for his kindness, without any request on my part, he gave me a letter of introduction to the Director of the Museum at Kyoto. Similar courtesies were shown me there, for instance, a large screen as taken into the courtyard, so that I could have sufficient light to photograph it.

In 1929 following the Pacific Relations Conference at Kyoto, I went to see the Imperial Treasure House called the Sho-so-in at Nara. I told the Director about the kindness extended to me years ago at the museums at Kyoto and Nara and from what he said I judged that these earlier courtesies had been extended to me by friends of his, who were grateful for my appreciation of oriental art. He also showed me special courtesies. These experiences taught me that the way to the heart of Japan, which is also the way to the heart of China, is through an understanding and appreciation of their art which they love and treasure.

After my husband passed away I came to Eugene to live, because my son Sam Bass Warner, was teaching here in the University Law School. I found the students not at all internationally minded not at all interested in giving the foreign students a happy time, not at all appreciative because these students had been chosen to come to the United States, to the State of Oregon, and to the University of Oregon, to get their education and form their friendships. So I went to work to see what could be done to change this situation, and to arouse in our students some understanding of the brotherhood of man, all the children of one Father. My mother, Clara Foster Bass, showed me the way. Some years she provided a building in which she established a museum of Colonial art, a museum library for books on New Hampshire, and an auditorium. This is known as the “Historical Building” at Peterborough, New Hampshire, and was established for the purpose of instilling in the hearts of the people of New Hampshire, a love for all that is good in the history of the state.

My first step was to give the University my then small collection of Oriental art, and since then I have made six trips to the Orient to improve and add to the collection. My friend Mrs Seaton, Mrs Potter, and Mrs Perkins have gone with me to the Orient, facing the dangers of a war-ridden country and the siege of Peking, in order that this museum collection might be built up. And above all my son Sam’s deep interest and cooperation, financial and otherwise, have encouraged me every step of the way, and had this not been his attitude, this museum work would never have been undertaken and carried out by me.

It was thru the untiring efforts of Mrs Gerlinger of Portland, President Hall, and Vice-president Barker that the funds were collected for this building which was built to house the Murray Warner Collection. I am most grateful to them, and to those who responded so generously to their appeal, and especially am I grateful to the people of the city of Eugene for their share, and to Dean Lawrence for having the vision to plan such a beautiful building, and to Dr Kerr for his cordial cooperation and encouragement which made the installation of the collection in this building possible, and to the Board of Higher Education for their kindness and generosity.

And now, I hereby present to the University of Oregon, in the State of Oregon, subject to my Deed of Gift, this collection of Oriental art…my hope and prayer is that it will be a great blessing to the University and to the State of Oregon…that it will always be a channel for International friendship and understanding between our students and those of the Orient and that this friendship and understanding will continue unabated throughout their lives.

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Transcript:

Vol. III-22 of the American Council, Institute of Pacific Relations

American Council Institute of Pacific Relations129 East 52nd Street • New York City

Vol. II-22

November 17, 1933

Issued fortnightly

Annual Subscription $2.00

Memorandum on Silver

This memorandum is taken from a manuscript prepared for the Economic Hand Book of the Pacific Area, to be published by the Institute of Pacific Relations in March, 1934

COUNTRIES of the Pacific play a predominant part in both the supply and demand for silver. Mexico, the United States, Canada, Peru and Australia account for nearly %90 of the total world production, while China and India have long been the most important consumers of silver. The sharp fall in silver prices; its greatly curtailed use as a monetary metal; the numerous proposals for raising and stabilizing the price, which culminated in the silver agreement reached in London, July 1933, are thus of tremendous importance in the Pacific Area.

The Supply of Silver—Mexico is the leading silver mining country of the world with the United States, Canada and Peru following in importance. In recent years the world supply of silver has been greatly augmented by the sale of demonetized coins by various governments following the debasement of the silver coinage or the adoption of the gold standard.

The following tables show the production of silver and the supplies other than production, during the post-war period:

SILVER PRODUCTION IN PRINCIPAL COUNTRIES, 1920-1932

(million fine ounces)

1920

1921

1922

1923

1924

1925

1926

1927

1928

1929

1930

1931

1932

United States

55.4

53.1

56.2

73.3

65.4

66.2

62.7

60.4

50.4

61.2

58.4

32.0

24.7

Mexico

66.7

64.5

81.1

90.9

91.5

92.9

98.3

104.3

108.5

108.7

105.7

109.0

69.3

Canada

12.8

13.1

18.6

17.8

19.7

20.2

22.4

22.7

21.9

23.1

26.2

26.1

18.3

Peru

9.2

10.0

13.2

18.7

18.7

19.9

21.5

18.3

21.6

21.5

--

9.3

6.3

Australasia

2.7

5.4

11.5

13.8

10.8

10.8

11.2

10.3

10.3

10.4

--

9.2

9.7

World

173.3

171.3

207.8

246.0

239.5

245.2

253.8

254.0

257.9

261.7

243.7

196.0

168.7

SUPPLIES OTHER THAN PRODUCTION—ESTIMATES

1920

1921

1922

1923

1924

1925

1926

1927

1928

1929

1930

1931

1932

Debasement of British Coinage

--

--

24.0

25.0

2.0

7.0

0.7

1.2

5.5

10.0

--

--

--

Demonitized European Coins

18.0

31.0

19.0

20.0

18.0

23.0

7.0

8.0

32.0

10.0

22.0

--

--

Sales by Indian Gvt.

--

--

--

--

--

--

--

9.2

22.5

35.0

29.5

47

69

Total Other Supplies

18.0

13.0

43.0

45.0

20.0

7.0

0.7

18.4

60.0

67.0*

71.5†

--

--

New Production

173.3

171.3

207.8

246.0

239.5

245.2

253.8

254.0

257.9

261.7

243.7

196

168

Total Supply

191.3

202.3

252.8

291.0

259.5

252.1

254.5

272.4

317.3

327.9

315.2

251

230

Price, N. Y. (cents per 1 lb. average)

100

2.6

67.5

64.8

66.7

69.0

62.1

56.3

58.1

52.9

38.1

28.7

28.1

*Includes 12,000,000 sound by French Indo-China

†Includes 20,000,000 ounces sold by French Indo-China

Control of Silver Production—The control of silver production is highly concentrated, mainly in the hands of American and British interests. American interests control all the domestic output, amounting to 23% of the world’s total; about 75% of the Mexican output;33% of the Canadian production, and 90% of the production in Peru. British capital controls about 22% of the world’s mine production, located in Mexico, Canada, and Australasia. As regards refinery production, American interests control approximately 73% of the world total, 52% being located in the United States and the remainder in Mexico. British capital controls about 11%, in Canada, Australia and Burma. Japanese interests control 10%, located entirely in Japan.

Silver as a by-product—Silver is invariably found amalgamated to a greater or less degree with other metals, chiefly with lead, zinc, copper and gold. As a result, a large proportion of the world’s silver supply is independent of the silver price of its continued production, as long as the amalgamated metals continue in demand. The United States Bureau of Mines estimates that only about a quarter of the world’s silver production is produced from ores depending on silver for over 80% of the recoverable value. This factor is of great significance in any plan for restricting or regulating silver production and also in estimating the importance of the decline in silver prices to producers in general.

Demand for Silver—In the consumption of silver, purchases by China and British India are by far the most important items. Indian imports are in the form of bullion and jewelry and are intended entirely for the Indian people; the Indian Government having been, since the adoption of the gold standard in 1926, an important seller of silver derived from demonetized coins. Chinese consumption is of a different type. China is on the silver standard and the Chinese Government therefore buys silver regularly for coinage purposes. In 1931 the net imports of these two countries accounted for 45.5.% of the total sold that year.

The second item in the demand for silver is it use in arts and industries, chiefly in the United States, Canada, Great Britain and Germany, and the third is its coinage as a subsidiary metal in Western countries. The following table shows the world movements of silver in 1930 and 1931:

SILVER, THE MARKET, 1930-1931

SUPPLY

1930--Millions of fine ounces

1930--% of total

1931--Millions of fine ounces

1931--% of total

New Production

246.8

77.5

196.1

76.2

Sales by Indian Gvt.

29.5

9.3

35.0

14.1

Other Gvt. Sales of demonetized silver

42.0

13.2

24.5

9.6

TOTAL

318.3

100.0

255.6

100.0

DEMAND

Net Indian Consumption

94.5

29.7

57.0

22.3

Net Chinese Consumption

123.0

38.9

59.0

23.1

TOTAL

217.5

68.6

116.0

45.5

German Consumption

8.0

2.5

28.2

11.0

Arts and Industries, U. S. A. and Canada

29.5

9.3

30.5

11.9

Arts and Industries, Great Britain

6.0

1.9

10.0

3.9

Arts and Industries, Mexico

1.0

.3

1.0

.4

TOTAL ARTS AND INDUSTRIES

36.5

11.5

41.5

16.2

COINAGE

U. S. only

6.1

1.9

2.4

1.0

Hongkong

14.0

4.4

--

--

Otherwise unaccounted for

36.2

11.4

67.5

26.4

TOTAL

318.3

100.0

255.6

100.0

Silver Markets—The silver market is a wide one, including not only trade in bullion, but also the silver-currencies foreign exchange market. The four principal silver markets are Shanghai, Bombay, New York, and London. Most of the world’s mine production passes through New York and San Francisco, a large volume going to London for sale and transshipment to the Orient. Shanghai is the chief receiving port for silver, Bombay being the next in importance. The silver markets are closely interrelated. Chinese buy and sell in New York, London and Bombay. Americans and Mexicans sell in London, Bombay and Shanghai. British Indians trade both way in London, New York and Shanghai. The following table shows the silver shipments from important ports, 1928-1932:

SILVER SHIPMENTS FROM IMPORTANT POINTS

1928

1929

1930

1931

1932

San Francisco

To China

62,637

57,111

45,340

15,719

13,642

To Japan

11

--

--

50

--

To India

--

--

757

577

--

To others

--

--

--

4,491

674

New York

To England

892

151

5,292

11,648

1,574

To Germany

4,269

2,774

2,637

7,719

2,404

To China

36,903

64,102

51,573

20,695

21,479

To India

35,599

16,819

24,554

20,610

652

To others

2,686

248

89

609

440

London to the East

To India

£4,012

£3,948

£5,648

£3,137

£639

To China

2,314

1,160

1,363

872

1,370

To Straits

198

--

12

64

67

Silver Prices—The history of silver in the post-war period has been one of the record prices in 1919 and 1920; a subsequent sharp and continued decline; and a long series of proposals for stabilization of production and raising of prices, mainly sponsored by the silver-producing interests in the United States. The boom in silver during and immediately after the war resulted from the heavy purchases of war materials by European countries in the Orient, necessitating payment in silver; from the constant rising level of commodity prices and industrial activity, and from the pitman Act of 1918 whereby the United States government undertook to purchase, at not less than $1.00 per fine ounce, sufficient American silver to replace that sold to Great Britain and exported to India.

The collapse of silver prices in 1920 was brought about primarily by the financial policies of various governments. In March, 1920, the British government, to prevent illegal melting of silver coins whose intrinsic value had exceeded their face value by 33%, reduced the silver content of subsidiary coins from an original fineness of 0.925 to 0.500. Between 1920 and 1938 thirty-two countries followed suited, eight of which abolished silver coins altogether. The sales from this demonetized silver from 1920 to 1930 amounted to 225,000,000 fine ounces.

In 1926 India adopted the gold standard, and upon the recommendation of the Royal Commission of Indian currency, the government began the sale of a large percentage of its stock of silver. In 1930, French Indo-China also abandoned the silver standard and unloaded heavy supplies of demonitized coins. In February 1931, silver prices reaches an all-time low of 25 ¾ cents per fine ounce. Production was greatly curtailed, but the decline in purchasing power of India and China, resulting from the general economic depression kept consumption far in arrears of supply:—

PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION OF SILVER

1929-1932

(millions of fine ounces)

New Production

Other Supplies

Total World Supplies

1929

261

67

328

1930

244

72

316

1931

194

47

251

1932

161

69

230

CONSUMPTION

India

China

Germany

Arts & Manufactures

Coinage

Unaccounted For

1929

82

137

12

44

25

29

1930

95

123

8

36

20

34

1931

57

59

28

42

21

56

1932

12

40

23

31

48

54

AVERAGE PRICE—PER FINE OUNCE

London Spot

New York official

1929

24.5d

52.9 cents

1930

17.6

38.2 “

1931

14.6

28.7 “

1932

17.8

27.9 “

Efforts at Regulation of Silver Prices—There are two schools of thought regarding the desirability, means and results of raising silver prices. The silver producing interests hold that the decreased use of silver has brought about the collapse in price which in turn has caused an unprecedented shrinkage in international trade, and is an important factor in the under-consumption of commodities since it has reduced the purchasing power of virtually the entire Orient. A notable exponent of this school is Senator Key Pitman of Nevada who has been indefatigable in introducing silver into wider use as currency, and in stressing the importance of higher prices for silver as a stimulus to United States trade with the Far East and Mexico.

On the other hand, many economists hold that the decline in the price of silver is the direct consequence of the general economic depression and of its effect upon the gold value of the exports from Oriental countries. The amount of silver which India and China can buy depends on the buying power of their exports and the decline in silver prices is a result, rather than a cause of the decreased volume of Oriental trade. According to this line of thought, a rise in the gold price of silver, without a corresponding rise in the prices of Oriental export goods, would encourage imports into the silver-using countries, diminish their exports, and necessitate an increased export of silver to balance their international payments, causing a further upsetting of the silver market. An economically sound advance in the world price of silver, therefore, is contingent solely upon an increased demand for silver on the part of Far Eastern countries, which can only arise when China and India can sell their products in greater volume and at higher prices in the world markets.

Repeated demands on the part of silver producing countries for international action to raise silver prices led to the forming of a sub-committee on silver to report to Committee on Monetary Stabilization of the World Economic Conference in London. A provisional agreement was drawn up and signed on July 22nd by delegates from India, China, and Spain as the most important holders of silver, and from Australia, Canada, the United States, Mexico and Peru as the principal producers.

The main provisions are as follows:

For a four year period beginning in January, 1934:

1. The Indian Government will not sell more than 140 million ounces—an average of 35 million per year.

2. The Spanish government will not sell more than 20 million ounces.

3. The Chinese government will not sell silver from demonetized coins.

4. The government of the producing countries agree to buy or otherwise withdraw from the market a total of 35 million ounces per year. This amount has been apportioned as follows:

United States

24,421,410 ounces

69.78%

Mexico

7,159,108 “

20.45%

Canada

1,671,802 “

4.78%

Peru

1,095,325 “

3.13%

Australia

652,355 “

1.86%

The chief beneficiary of the agreement, apparently, will be the British Empire. Canada and Australia have agreed to absorb less than 7% of the 35 million ounces, although British capital controls nearly 22% of the world output. The government of India, while agreeing not to increase its sales beyond the previous maximum in any one year, retains its right to continue sales to governments desiring to pay their American war debts with silver. Under the Agricultural Adjustment act of May 12, 1933, the President of the United States was authorized to receive payment of these debts up to $200,000,000 at an arbitrary value of 50 cents an ounce. In making its war debt payment, June 15, 1933, the British government purchased 20 million ounces of silver in India at a cost of a little more than $7,000,000, and with this obtained a credit of $10,000,000 at the United States Treasury.

The time limit for ratification of the silver agreement is April 1, 1934; it is being stipulated that if any of the silver-producing countries withhold their consent, it will still become effective if those which ratify it make arrangements to buy or withdraw from the market a full allotment of 35,00,00 ounces.

Sources:

H.M. Bratter, The Silver Market, U. S. Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, 1932. And also

Silver—Some Fundamentals, Journal of Political Economy, June, 1931.

The Congressional Record.

The Economist, London; and Finance and Commerce, Shanghai.

News Items in the British, Chinese and American Press.

The American Bureau of Metal Statistics, Year Book, 1932.

W. P. Rawles, The Nationality of Commercial Control of the World Minerals, New York, 1933.

I. P. R. MEMORANDA

VOLUME II—1933

Coal in Japan and Manchuria

Import Trade with the Philippine Islands

Chinese Government Finances

Japanese Mandated islands in the Pacific

The Chinese Boycott

The Far East on the America Screen

Construction in China

Chinese Eastern Turkestan

International Cooperation in China’s Public Health

Basic English as an Aid to Language in the Pacific

Effects on Japan of Depreciation of the Yen

Depreciation of the Yen: Effect on Japan’s Foreign Trade

United States Investments in Japan

Sugar

Railway Construction in Manchuria

Tin

Anglo-Indian-Japanese Textile Competition

Japanese Rice Control

Wheat

Government Subsidies in Pacific Shipping

Some Notes on the Study of China and Japan in American Schools

10 CENTS A COPY

$2.00 A YEAR

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

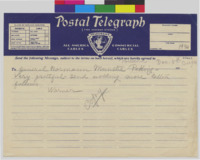

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Transcript:

Peking, 12 June, 1933.

My dear Friend,

Thank you for your letter of May 7th, posted May 11th, that came here on the 9th. Of course, all that you say about God being all Goodness and Perfection, hence cannot and does not send his His children any evil in any shape or form, is quite true, and knowing this, we also know that whatever appears to us as evil has no mandate or right of existence and forever, and we therefore know that it must—in God’s own good time—disappear. What love does come to us comes in various forms, for various reasons. In the first place, I think, and our wrong thoughts, words, and deed call down punishment on us, and this, I think does not only apply to our present life, but, as we take our vulnerability with all its shortcomings with us into the next life, so we, when we came into this life brought with us, the faults and failings of our previous existence or existences, and we are paying up—in the shape of sorrow and suffering—not only for this life, but also for the many previous ones. This is the only reasonable explanation that I can find, when I see so many good and worthy people suffer more than their apparently less good and worthy neighbors. That is one reason for suffering, another may also be that suffering hideous tribulations may be a link in and mental, spiritual development forward and upward. This, I also believe is a reason why we have to go through so much.

Now, take the present depression that affects the whole world; what is is the reason? I should say that the so-called “Great War”, and all the hate and wrong thinking in that direction that it created and which has not, as yet, been eradicated from the minds of man-kind. When we all have good-will and only kind, helpful thoughts for our fellow-beings, we shall have no more depression. This depression is the image and likeness of egotism and selfishness—every person, every nation, only thinking of itself, and its own seeming interests. Importantly, it is easier to abort a wrong that than to stop it, regret it, and eradicate it. It takes effort, good-will, and time and these things have first to be provided before one can reasonably look for any improvement.

There was a ray of sunshine in your letter that gave me great pleasure. You say you will pick the thing you want when you come to Peking. Hoorah—hurry up and come, please. You cannot come soon enough, and as I sitting here love writing to you, I am writing to you and telling you that that is the best news I have had for many a day. You have said so, my dear Friend, so that is a promise, and I am surely only too keen to you to your word. There has been no regular service in Peking since I gave it up to the other some 3 years ago. I am looking forward with the greatest pleasure to having services again with you—and you say Mrs. Perkins.

I am grateful and thank you for all your kind thoughts for me, and I thank God for sending you my way, and for our mutual friendship, and so I send you the best of all good wishes; ay God be with you and bless you.

All kind and helpful thoughts and wishes to you, my good Friend,

Your old friend,

Normann Munthe

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Transcript:

Peking, 10 May, 1933.

My dear, good Friend,

Yesterday I went to the Bank to receive the money that you so kindly had sent me. I sent you a telegram, in order to thank you and to show you that I fully understand the situation, and deeply appreciate your willingness and readiness to help me. I again sincerely thank you.

As I explained to you in my letter, the situation is a peculiar one. I have plenty of valuable assets, but it is impossible to turn them into ready cash at present or in the immediate future, as there are no buyers—all are sellers. The Government owes me plenty, admits it, promises to pay and then simply declares it has no money. I had tried before I wrote to you to get them to pay me at least enough to live upon, month for month, but they could not manage it. All the money they can lay their hands on goes to and for the war. The Banks (foreign) will only advance limited loans on property, and as foreigners, outside of missionary bodies, cannot boy or hold property in Peking, the Banks cannot legally hold or loan anything on Chinese title-deeds/ As you can readily imagine, it has not bee, is not a pleasant position in which I find myself placed., and added to my other worries, I should like to look [] cheerfully upon the immediate future than what I do. On the other hand, I do not wish you to think for a moment that I feel demoralized or do not thank for all His Goodness to me, for I do. I know, that come what may, He will, in the future, as in the past, find a way out for me, however dark the outlook my appear to human senses. But you know how it is, and [] morbid, human self, likes to look ahead a little, and to feel that there is enough for daily needs. I am so glad for Chri. Sc. and for the blessed understanding of God, that it has brought into my life. But for this knowledge, where should I have been by this time? We are all so apt to feel worried at times, instead of contenting and friendship, and go over our past life with its many experiences, and then see and realize how God time and again, all the time, has kept His hand over us. When I think of all that He has done for me, and how little, if anything, that I have done in return for His Goodness, then I feel ashamed, and I can only say: God be merciful to me, a sinner!

This winter I passed 2 months in my bedroom, but this last week, I have been able to go down in the Garden, and to-day I went to the office; yesterday was the first day outside my gate when I went to the Bank.

I am so grateful for your friendship, I feel I can speak to you as to nobody else. I always feel you are such a fine, loyal friend. All kind and true thoughts and wishes to you, my good friend,

Ever your friend,

Normann Munthe

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Transcript:

Kuo Hsi Landscape

MWCh32:K9

Peking, 11 April, 1931.

My dear Friend,

Thank you ever so much for your welcome and interesting letter of March 8th, for your telegram with money for the roll, and for your kind and thoughtful telegram about class-instruction. All right, dear Friend, I note all you say, and quite agree with you. I had a good laugh to myself and smiled to you, when I read aout the kind donors who sent rubbish—a not unusual thing in America, I have been told. Your idea of getting rid of these gifts by declaring they must given to you is an excellent one. When I wrote to your President, I told him in my letter that my gifts were not prescribed to the University of Museum, as I knew no-one there, but that they should thank you and not one, as my gifts were there on a/c of you. In selection of gifts, it will not always be possible for you to avoid offending somebody’s susceptibilities—that, of course, may be awkward, but cannot be helped. You say it takes time and work to get things in order—my good Friend, think of what I have had to do in the first instance, in finding out all and everything I can about each object and then proceed to put it down and get the things ready—and off! When I now think of it, I feel mighty thankful that I have got off what I have. The Chinese Government has prohibited the export of art books and manuscripts, all sculptures, and bronzes. It is but a time when paintings and porcelains also will be forbidden. All imperial things are forbidden, if they can catch you.

I am welshing here with a newspaper-cutting in French, from which you will see the spirit of the Chinese on this subject: I am sorry that your bronze has not been forwarded to you. It was clearly [] out to Mr. Furman, and the container was marked for M>W. and he was requested to forward it at once to you. There may be some red tape at the bottom, but I shall attend to it surely, when I get out.

Your telegram for Mex1600 paid for the roll. In looking up you’re a/c I foud that there were Mex1098 to your credit, for which I have bought a Chien Lung Jasper Jade Vase and a very good crystal, both originally from the palace. Mr. Abert requests me to tell you that your port of entry is no longer Portland but Seattle, and that you will have to attend accordingly. I have forewarded you the 3 things, and enclose herewith the Consular Invoice. We hear that the shipment, []drum orders from Washington have been issued as regards antiques that pay no import duty. For useless red-tape recommend me to your free America. The old saying about: “God’s own country and the devil’s own Custom House,” is evidently but only too true.

The details of the roll are as follows:

Sung: Kuo-Hsi—Landscape Roll

On opening the roll: [names less than clear]

1 seal of Wan Pin Chiang

1 “” Prince You (Shan Chih)

1 seal of Wang Tao-heng (Sung)

1 “” Chao Kuai Pan (Yuan)

2 seals of Teng Chi-chang (Ming)

The roll comes from the Imperial collection, as also shown by its brocade-wrapper. You can be mighty glad that you got the things you did when you were here before—there have been no more forthcoming.

I have had my hands more than full these last 3 month—and am not through just yet—intrying to have my big imperial things by getting them out of the country before it is too late. It has takena tremendous lot of work, and cost a lot of money in dues and transport.

I sent another collection of sculptures to Los Angeles last September, but they were stopped in Tientsin and have been confiscated, without any previous articfication to the effect that export was forbidden. They do just as the please, and duties are about 6 times as much as they need to be. But all this, we can [] when we must.

I am trying my best to get away about the end of this month, April. Yes, it is time, as soon as I know, I shall write write to the C. P. Sanatorium of San Francisco. O.K. I note all you say about [] and teachers. Re the 9 collections of Chinese Art on exhibition in Los Angeles; I have heard about them, but there is nothing either singly or combined in the [] to emperors in any way with some many things. Sure, I shall look into Mrs. Richardson when I get here. I have always heard her well spoken of.

My wife is busy on her continuous [] of the history of China, from the end of Chien Lung to the Revolution and it suits her to stay on here. Godfrey is doing very well indeed, and had his first exhibition not long ago; he has certainly got talent, and zeal and application. I shall let you know first of all, as soon as I know myself when I shall be there. My—won’t we have a talk, no, talks together! I am just writing to you as I write this, and saying: another fortnight and I [] to be out of this and bound for better conditions and surroundings in every way.

All loving and kind thoughts and wishes to you, my dear Friend,

Your true friend,

Normann Munthe

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Peking, 2 June, 1932.

My dear, good Friend,

I am just back again in Peking, and my first letter to America goes to you. When I got on-board the steamer in Los Angeles, I found your thoughtful gifts to me, and I was amazed at the [] and work you had gone to to send me these letters, partially written by yourself, partially type-written. My dear, dear Friend, how could you do it all? Well, of course, it is no new thing to me, to find how big and good and warm your heart is, but for all that, when I realized the work done, I also realized that it was a work of love on your part. I am very grateful to you and thankful to God that he has given me such a friend./

The passage across from Los Angeles to Manila direct was good; I was the only passenger, and had the ship all to myself; the Captian, officers, and crew were so nice and kind to me; I did not need my trunk once, but still had to stand up, or sit up, or lay down on the [] which was hardier than the trunk. From Manila, we we went to Hong Kong—Shanghai. My wife had hoped to meet me in Hong Kong on her way home, but her steamer was delayed, and I could not wait. She and Godfrey had gone to Hong Kong to see her son and daughter in law; they were then later to go to Harbin and by rail through Manchuria and on by the Siberian Railway to Berlin, where they are to stay for Godfrey’s studies.

I went to Nanking, where the government kept me 10 days, and wanted to keep in order that I might help them with some reorganization work for which they think me the most suitable person, as I know Chinese conditions so swell. It is the biggest thing that has now come my way, as it is for all China, and if only my health was all right, I should be so pleased but you see, as I do not sleep at not I cannot do any work in the morning or forenoon, but shall have to do all my work from 12 noon till evening, an arrangement that may suit me, but not the others. However, God has arranged all so [] and well before that I firmly believe that also this time, He will keep his hand over me. As my Lady says: Step by step step shall those who trust in Him that God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble.

When I think of my time in America, it seems a horrible nightmare; and I should not live it over again for all the money all the world, and mind you, for all that, if I had not stayed as long as I did, I could not have put my house in order as I did.

God moves in a mysterious way, His wonder to perform, we do not always see His ways, but we may at all times be sure that if we do our little best, He will never fail us, but works out His plans for us—guides us and leads us. What a [] and help it is that this is actually so./ And so, enough for to-day, I am somewhat tired, but wanted to write first to you.

All loving and kind and true thoughts and wishes to you, and may God be ever with you, to guide you and lead you.

Ever your true friend,

Normann Munthe

P.S. You know much I wish to know you well and happy!

NM

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Transcript:

Pasadena, 3 April 1932.

My dear Friend,

Thank you ever so much for your 2 letters, of 17 & 24 March. Well, this is my last letter to you, this time, in this country. For I am leaving here on the Norwegian freighter “N[]”, on the 9th, and your letter to me, will be addressed to Peking. Needless to say that all my good and kind and loving thoughts go to you, wishing you all that is good. My stay in this country has been a trial and a tribulation, but even so, it must have been good for something. As I see it, I could not have put my affairs into legal, safe shape if I had been well and able to proceed. Granting this, we have granted and accepted what was most important, perhaps. Personally, individually, my stay has been more or less of a nightmare. Frankly, it has tried my faith and trust in God hard, to see both of us suffer suffer. You, who are the best and most loyal friend whom I know, and who at all times are true, loving, and kind and helpful to your fellow beings, and trying to please God in the best way you know how. And there you are, going on suffering all the time. I certainly cannot see my way clearly in all this, for I also have had to face a hard fate, it seems to me. And this, no doubt, we are both wrong. For it has been said that those who suffer most on this side shall have it easier on the other side. Well, I hope it may be so.

We like to grumble and think we are hardly [], and indeed it does seem hard at times, and hard and difficult to understand, still in our deeper-down [] understanding and knowledge, we should think and feel that whatever comes to us is best, just so, only we cannot see it; but it is just the same.

Everything in connection with my affairs has been satisfactorily arranged. My art collection in the museum in the hands of a committee, considering of [names less than clear]: president Rufus von Kleinbaurd, Hector Bryan, Professor Dr. Van Koeular, H. Comestock (Museum), and Rev. House. This committee will canvas for subscriptions to buy the rest of the collection, and feel confident they can do so, as soon as better times set in, which they expect in the course of the year; but they are starting canvassing at once, as far as that goes. My auxiliary collection is in the hands of the Rev. K. House, a good, reliable and capable man. Mr. Furman is evidently out of it. I am telling you all this somewhat circumstantially, as you have so often referred to it./

I thank you for each an all loving thoughts that you have sent my way while in this contry, and can assure you they have found a ready response in my heart.

All loving and kind and true thoughts and wishes to you, and may God ever [] you, my good and loyal Friend.

Ever your friend,

Normann Munthe

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Transcript:

Porcelain Jar

See file Albert, G. E. Peking, China

Pasadena, Tuesday, Dec 1. 31.

12/1/31

My dear Friend,

Thank you so much for your letter of No. 28th, which came yesterday. Yes, to be sure, evil does try to estrange us from God, and from the kindess of Him that Christian Science has brought to us. The way, wherefor[e] our seeming existence and power of these many shapes and forms that evil takes, [], I frankly admit I cannot understand it all, and find it hard to overcome its consequences. I [] up and honestly know the un-reality of all these evils and their claims on human nature, and these I suffer [] them, and their impositions. I have not asked any practitioner here to help me, so far, though I have suffered, and do suffer a great deal. I have tried to bear it, so as to see exactly what the practitioners actually can an and does do for me. I have the intention of taking your advice, and all Mrs Richardson to work for me, in fact I rang her up yesterday evening about 7:30, but did not find her at home; shall try again. When I look at my arm case, I am also thinking of your case; without in any way being [], surely I am justified in saying least we [] try our best to be loving and kind and helpful towards our friendship, and why, or why, is it that we are not better? Well, it is always difficult to talk about yourself, but when I am doing it for once, I do it, because these thoughts come and came again and again, and I cannot find a satisfactory answer for them. All I can find to counter these questions with is what Mrs. Eddy says about human existence []: ‘human existence is an enigma”—perfectly true, of course, but it does not answer the question: why is it so?/

But the same kind of thoughts must have presented themselves to you from time to time, and I dare say, you think pretty much the same?/

You ask me about the Sung jar that I sent you. I shall tell you what I know, and what I do not know about this ware. The Chinese call this ware, like so many others, merely Sung ware: the reason being that the objects being thus designated are to name that the original names—if they originally had any special name, have in the course of time, got lost: Tzu Chan is as far as I know, a piece of manufacture of different kinds of ware, in Honan province and for the slect times down to the present day. Hebson in Hui Fook or [] many wares as Tzu Chan-ware, with what justice I cannot say. I fancy this certification of so many different kinds as Tzu Chan-ware, will only stand till we, though systematic and scientific excavation in China—and this is but a matter of time—shall be in a position to certify these objects more concretely. Of course, a rose by any other name smells just as sweet, so any new certification will in no away interfere with our appreciation of these objects. To look back then: Hobson calls this ware Tzu Chan ware, and so we do likewise, for the time being: It is very nice—the genuine ones, and I had not seen any, till I got these from the Emperor. They had been paired to some of the banks, and I got them by redeeming them and by paying [] to the E. Anything imperial is in a better condition than anything that you can get on the market, because only the very best things were sent to and kept in the Palace; as you will also observe in your picture rolls. I should [] [] I had to to a museum [] from America, when I was in Peking, and asked him if he had seen of this kind in America, and he said, yes, he had seem one piece at a dealer’s in San Francisco; it was not as large nor so good as mine—which again was not as grand as the jar that you have got and the price was $3.000. I reckoned the price of the jar would be about 10.000 at a dealer’s, and therefore [] the price of $6.000 for the pair on my invoice here as you will see from [] prices—which kindly refer to me for the [] here. When you asked me to get you something for $800, I had first in mind to give you 2 smaller ones, but when I came to look over the [] collection of what I had sent over this time, I concluded I wanted to give you something of the very best, and something that you did not have. Mr. House told me that Professor Emmonds [?] (Parnes?) had taken a great liking to this pair, and he thought [] want them, so finally I made up my mind to let you have one. The price to you is neither more nor less than $800 that you wanted to invest, for the one sent you. I shall when I go back to China, try to pick up whatever information I can on this subject and in due course of time, let you know./

Re Mr. F I am [] Mr. House and another friend in full chance of all the things that I have sent over this time.

As regards the original collection, I am trying to force a committee of trustees of lading museum-men here to take charge of it for the future. Mr. F. will be eliminated.

Enough for to-day. All loving and true thoughts and wishes to you, my dear Friend,

Ever your friend,

Normann Munthe

Air Mail

1931

Porcelain jar

Mrs. G. B. Warner,

Osburn Hotel,

Eugene, Oregon

L. P. A.

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Transcript:

Loaned—Wine-jar-bronze

C-1055 Porcelain $800=*

Pasadena, 19 November ’31.

11/19/31

My dear Friend,

You have no idea what a pleasure it was to me to have you here; though I much regretted to see you suffering from your accident. Why, why is there sickness and why are there all these trials and tribulations that seem part and parcel of this existence of ours? It is a question that so often comes up in my “question-box”! And to which I can find no satisfactory reply!? So often those, who seem to try the hardest to please god, seem to suffer the most, and again y question-box queries: why? To be sure, I knew, all we have go to do is to do God’s will, and all is well with us, but this does not answer the question to my satisfaction. So many explanations may be advanced, especially by the non-sufferers, and still, being as we are, we bear comparisons and we are not satisfied that we have not got more than our fair share. Still, let us be thankful that matter are not worse—they surely might be, you know; and let us be thankful for the good God sends us, though it is not always easy to rejoice.

Sorry, my good and loyal and dear Friend that I am not in a more cheerful mood to-day when writing to you, but this constant sleeplessness takes it out of me. Still I know all will be well, in God’s own good time and way and in thinking thus I am not thinking of myself alone, but perhaps more of you; I feel so sorry to see you suffer and to know it had [] to [], but patience, patience, it will surely come all right! I liked your friend, Mrs. Richardson, but I have not asked her or or anybody else for that matter, as I wanted to find out first what the effects of my new surroundings would be, so as to be able to know and to feel what was due to so-called nature, and what was due to the practitioner’s efforts, but I must tell someone, for it is getting too much for me again. I am not going to ask Mrs. Richardson or anyone else till I hear from you in reply to this, so here goes my “question-box”! Are you satisfied that she actually helped you, or are you only wishing to do her a good turn? In other words, do you consider her an efficient, successful practitioner? If you really feel she is, well and good, I shall ask her, and in that case, please send me a note. If you do not feel sure and confident, I shall try someone else. Now my dear Friend, think the matter over and act accordingly.

Mr. Hanes is kindness itself, and comes in every night from time to time, when he [] and [], the attacks are too much for me. Nobody could be more truly kind and authentic than what he is in every way. (C-1054) He is in this moment packing the Sung Tzu Chan wine jar with cover that I am sending you. We are sending the jar in one box and the cover in another and sending them in plenty-big boxes, securely and well packed. It is one of the finest specimen of this kind of Tzu Chan ware, and with the exception of one [] pair that I have, the biggest and finest I know of in this country. I got it from the Emp. [?] the antique stand was [], and there was no time to get a new one made. It was, or rather is, one of a pair, but someone has had particularly reworked this pair, and as I [] you to have the best one. I have divided the pair. I had originally originally included to give you 2 small ones of the same family, but as I looked all over my auxiliary collection, I came to the conclusion that I wanted to give you what I considered the best. I can only that it will be appeal to you as it does to us who have seen it and appreciate its quality and value.

And so, enough for to-day, I am getting tired, and I want them to go by to-day’s mail. The parcels are going also, and are being sent y the American Railway Express, Mr. House tells me.

All loving and kind and true thoughts and wishes to you, my dear Friend,

Ever your good friend,

Normann Munthe

(*Mrs Warner told me in 1933 that she paid Gen Munthe 800.00)

1931

Wine Jar loan

Jar

Mrs Murray Warner,

University of Oregon,

Eugene,

Oregon.

From

General J. N. Munthe

923 E. California Rd

Pasadena,

Calif.

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Transcript:

Noble, [Harold]—letter

Peking, 22 December, 1930.

(Please give my kind wishes to Mrs. Perkins: NM)

My dear Friend,

Your business-letter, as you call it came, and I at once sent for Mr. Albert, gave him the fee to pay for the university, and here you are. I thought it best to make it as official as possible. Your telegram: “Very grateful. Sent nothing more. Letter following. Warner.” came a little while ago, and I am going to wait in answering it till your letter comes, also as regards the remittance of Mex$4.287 that has come to hand.

Now—yes—I agree with you. I also can hardly wait till I come across to see you. I am not delineating in anyway and God knows that I leave everything in His hands, but if God does not show me that He does not want me to go, I have every intention of coming, leaving here sometime in April. From a mental point of view, I seem to feel that I cannot stand another year here—I must get away. These last 10 years, I have been improving as regards the violence of the attacks, but I find that I cannot stand [] that I used to stand. God has been, and is, wonderfully kind to me, and but for Him and His Omnipotent Love, I should not be here, and my dear Friend, I do not want to go till I have received my plan in giving the mony that I make to charity. In this, as in everything else, I have been and am constantly constantly asking God to lead me and to guide me in the way He wants me to go, and somehow I seem to feel that He will hold His hand over me and my work till it is n accomplished fact; and when it is, I shall feel that I have not lived my life in vain.

There is so much to contend with here, and I feel that I must get away in order to breathe a kinder atmosphere. A year ago, you two were here, and what a loving, harmonious time we had together; the happiest time that I had spent for many years, as I told you.

Of course, I am looking forward to seeing you again, and I hope we shall both together see as much of Christian Science as what we can, also visit some of the museums together. Well, well, my dear Friend, we, all of us, and the [] universes are all in God’s hand, it is for him to say what shall be or shall not be, but as I have said above: I seem to feel that I have His blessing in my undertaking. No news from Los Angeles; I fancy Mr. Furman has is difficulties, on account of the tightness of the money [], but all this does not worry me, for it is all in His hands and it is not a question of this or that, but all the Time of God and of what He decides, and whatever He decided is sure to be for the best. All loving and true thoughts and wishes to you, my dear Friend,

Ever your friend,

Normann Munthe

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Transcript:

Hotel Osburn

Eugene, Oregon

Copy of letter to Gen. Munthe

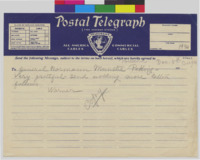

Wednesday, Nov. 19th 1930.

My dear Friend,

Here I am, back at Eugene ready to go to work—the new building is nearly ready, all but its front door & some varnish on the floors. As soon as these are finished, we expect to starting moving our things. It is a fine building—the rooms are lighted by electricity, instead of by the day light in order to keep our textiles, upon which the lovely paintings are all painted from fading—I am sure you will admire it when you come to see us.

As the gift of the collection to the university has to be carried out according to law, I am collecting all the receipts of the things I have purchased. I find that it is necessary to have a receipt—from Mr. Albert—for the things shipped in his name.

I am enclosing a typed statement for him to sign & I am asking you, my dear friend, to see that he signs it, dates it, and you, or some other adult foreigner also sign it as a witness—because the University requires receipts for everything—and quite properly. When it is finished, please return it to me as quickly as possible—as my report will be waiting for it.

This is only a business letter, I will write again soon and then we will talk about our beloved Christian Science. With all good wishes, for all good to you, dear Friend.

Faithfully yours

G.B.W.

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Transcript:

Oct-19-1930

(All loving and true thoughts and wishes to you, my dear Friend, your good Friend, Normann Munthe)

Peking 19 October, 1930.

My dear Friend,

Your good and kind letter of Aug 23rd. has been before some time, but I have been working for you all along and did not want to write till I had got off what I was after. First of all, here’s my hand and a good handshake for your letter, I see the logic and sense in what you say, no doubt. I should [] by the [] for some time and in that time think of nothing else and a pride healthy would no doubt come. There is no reason, [] or otherwise why it should not come, but the [] daily-ceremony claims of [] seem to ground me here, and the only solution I can see is to get away from it entirely. God willing and approving, it is my idea to get away from here in April next year. That God will keep His hand over me till that time, I firmly believe, as He will not leave His work half-done. He has shown that he approves of my idea to take what I have with money and give it to charity. I made my testament to this effect early this year, so it must [] came true in Good and [] and every/ As I have told you before, once in America, I shall communicate with you a once and we shall do all we can in Christian Science together, and after that the Museum. Just as it pleases and suits you as I shall be my own master as regards the disposal of my time. I have numerous invitations invitations to come and stay with people, but I am not fond of staying with others in contradiction to my wife, who adores it. It suits my wife best to remain here while I go on leave, as she is writing the continuations of he history of China, and can do that best here./

Begin here

As I told you in my last letter, I enclosed your bronze, well-packed and addressed to you, in the lot of bronzes that I sent by freight to Los Angeles. I can now report that your Imperial Capital together with the other things that I have got for you have been safely sent, and I enclose documents and photographs herewith.

Your crystal was mortgaged for $1200 and with interest he came to $1600. The bronze you paid for while here. I mean the important one. You asked me to be on the look-out for a painting, a roll, black-and-white on paper, well-attended []. I commissioned with my good man man, but so far nothing has turned up. If you have cash to spend, now is the time, for you get Mex 3.50 about for 1 gold. Of course, Chinese things are going up, but not so rapidly.

Not long ago, the crystal man told me he could get 3 fine pieces of crystal for $2400. I told him to buy them []. It was one vase, as tall as yours, one tripod with [], and one of Emperor Chien Lung’s official seals that he used when residing at the summer palace—all my [] things with inscriptions. I brought them at once for you and I am sure you will like them. There are inscriptions on all these and the translations will be sent you in due course of time, when the man who used to help me can find the time, he is too busy at present.

I have sent off almost another collection to Los Angeles, and have told them I intend to make them a gift of this and if they will [] at once—which I doubt they will, as money is scarce. Well, which getting things moody one of my good men brought along a pair of Yong-Cheng enamel [] []. The [] [] that I have come across and a splendid specimen of Yong-Cheng enamel-ware. I could not resist the temptation so bought them and having done so, came to the conclusion that one would be enough for Los Angeles, and that I would present the other to your museum, my dear Friend, so I have sent it with the crystals.

As I said above, these are all imperial things. While I remember it, there are in most crystals veins in the [], that others look like beaks As far as I understand it, a vein is generally feet, if on the surface, on one side only. A beak would be feet on feet on both sides. What you see on your crystals are veins, not breaks.

You sent me Mex $1702, if I remember rightly. I have paid out as follows:

One bronze bell $600

One crystal vase 1600

One crystal vase \

One “” tripod ----- 2400

“” Seal--------------/

I do not know exactly what Mr. Albert charges one, as he is in Tientsin, but we can say,

300

=

Mex 4.900

Pair -1702

=

Balance to me 3.198

I can correct it later, if wrong.

I shall send you the translations, as soon as the translator finds time.

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.

-

Correspondence between Gertrude Bass Warner and General Normann Munthe

Transcript:

Peking, 25 June 1930.

My dear, good Friend,

Thank you ever so much for your welcome, long-looked-for letters (3) written and sent during May. How I wish I could talk contents over with you instead of having to do so in writing! First of all, I feel very very sorry to hear you had had a claim of pneumonia [][][], I know what it means and I can only say: is it not believed to know that God has all pains and that it is always there, willing and ready help us? I rejoice to think that you had a quick and successful healing. I can honestly say that I am not self-righteous or think of myself as more or better than what I ought to, nor that I do not feel that God rewards me far beyond my deserts, but my dear Friend, at times, when I look around and see so many who do not try at all to please Him, being healthy and prosperous, I cannot see how it works out that both you and myself, who, without flattering ourselves unduly, surely can say that we try to please Him, how these [] from time to time. Is it, I wonder that we are paying up for our sins in former existences? I can find no other explanation.

I make what you say about your mother; yes, dear Friend, it is is very, very hard to be found fault with, when one tries one’s best to please, but bear in mind that she is nearly blind, as you as you say, and also bear in mind that we are never sorry for having been too kind and confiding, even if we are taken in from time to time. It is better to be too kind than the reverse. God is Love, and we must try to reflect it as much as we can, and I know no person who is keener alone to kindness than what you are, nor do I know of anyone, who shows in her acts that she is kind and thoughtful than what you do. I take my hat off for you and consider your friendship a gift from God—all sunshine and now shadows./