Producing Silk

If asked to name one term that characterizes Chinese civilization, one would have to say ‘SILK.’

Silk is, in fact, older than the political entity of China. It has influenced the life of China’s people since Neolithic times, when the idea of using this fine filament to produce elegant textiles was born.

Chinese philosophers have long associated silk weaving with maintaining proper order in human relationships, society and government. Just as a loom must be “dressed” (set up) with warp and weft threads in precise order so that dis-order will not cause any flaws in the finished fabric, a lack of order in society was believed to invite chaos. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that the Chinese term for warp—jing 經—is also used in the classical writings of Chinese philosophy intended to instruct how to synchronize the human world with cosmic order.

For rulers silk fabric was treasured as a precious gift, an award for loyalty and service, and a currency to appease China’s confrontational neighbors.

China’s aristocracy craved the elegant cloth. Their demand inspired technological innovations and looms that could accommodate the ever-more-complex weaving patterns demanded by fashion. Silk embroidery was celebrated as the finest adornment befitting the most precious ceremonial garments worn by the emperor, nobility, officials and priests.

Sericulture (silk production) and agriculture came to be considered as the two pillars on which China’s well-being relied. The old saying “men plow and women weave” reflects the traditional ideal of a gendered division of labor in which the people were well fed and dressed and the state could expect a steady revenue.

Millenia-long experience in the production of silk (in official workshops operated by the imperial administration as well as in domestic households) resulted in the most refinedweavings imaginable that were used for both clothing and decorative purposes. When Gertrude Bass Warner began to collect silk for her academic art museum, she aspired to present a large variety of silk objects, documenting the range from imperial robes and elite ceremonial hangings to modest sleeve bands (pieces made for an inventory in case a replacement became necessary). Even the most humble pieces became a canvas for the expression of auspicious wishes and messages disguised in poetic scenes. You are invited to explore the examples preserved in the collection here.

The basic weaves of Chinese silk

The arts of kesi tapestry weave and embroidery

Sleeve bands, collars and roundels

The basic weaves of Chinese silk

Tabby weave (pingwen 平紋)

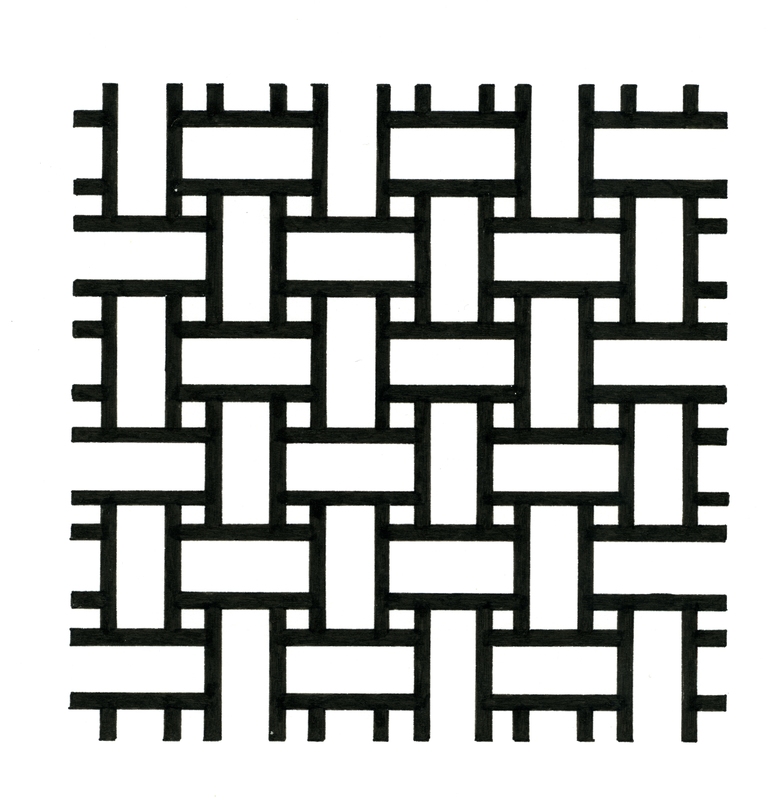

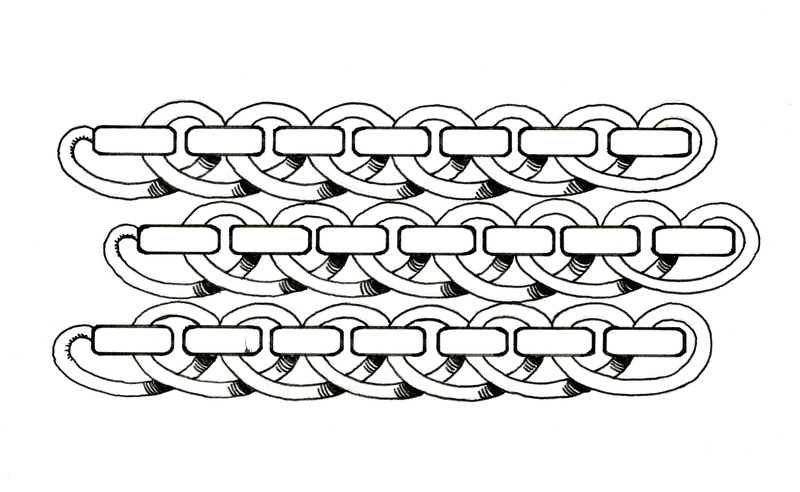

Plain weave or tabby weave is the simplest interlacing of warp and weft in an unvarying alternation: each weft thread passes alternately over and under the warp threads as in this hanging embroidery with scenes from the ‘24 Paragons of Filial Piety’ stories.

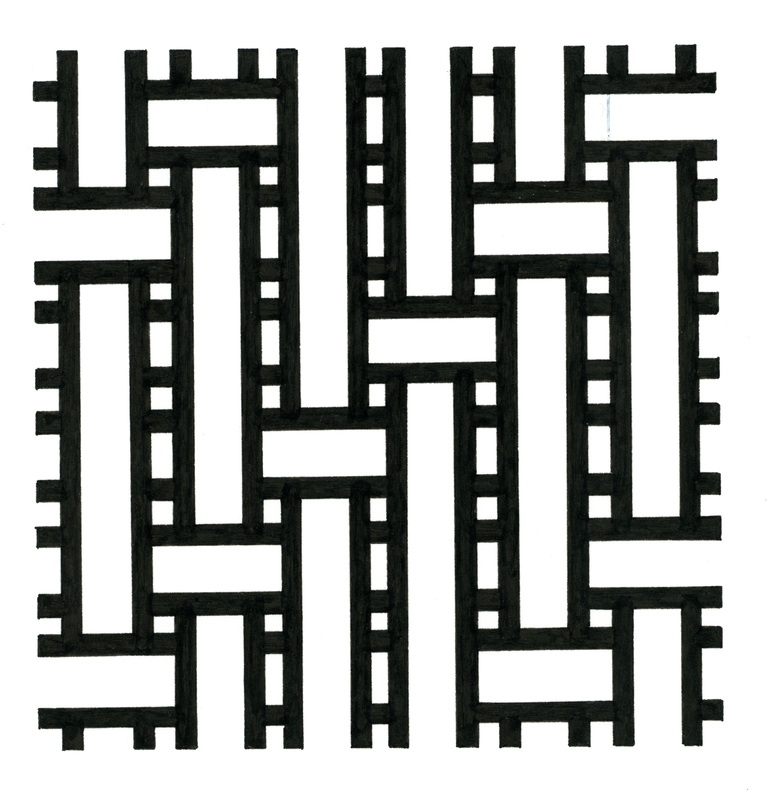

A variant to the tabby weave is the slit tapestry weave (kesi 緙絲) used for weaving pictorial patterns, when areas of solid color appear separated from areas with other colors. The weft is worked only part way across the warp threads and then returned (instead of passing from selvage to selvage). The area between discontinuous wefts where the areas of different colors meet creates a slit (kesi 1). In the detail of the hanging shown below the slits have been stabilized by simple stitches visible in the area where the red background meets the architectural structure (beneath the sleeve of the immortal holding the gourd).

To give the weave more structure the weft can be dovetailed around “scaffold” warps. This creates a “toothed” appearance (kesi 2).

Satin weave (duanwen 緞文)

Satin is a simple “float” weave. When every weft thread “floats over” (i.e., covers) several warp threads the weave is called “weft satin.” When every warp thread “floats over” several weft threads before a binding point, the weave is called “warp satin.” This festive hanging is made of un-patterned tabby weave that has been embroidered with the dramatic scene of a scholar dreaming of a woman and child.

Twill weave (xiewen 斜紋)

In a plain twill the wefts and warps each pass over and under equal numbers of the opposite set.

A twill shows a progressive succession of “floats” in a diagonal alignment, so that adjacent wefts never “float” over or under the same group of warps. The two faces of the fabric look identical, though with a reversed direction of the diagonal alignment, like in the green silk of this Daoist robe.

Regular zigzag, lozenge and herringbone patterns are achieved by reversing the diagonals at repeated intervals.

Selected embroidery stitches

Chinese embroidery has a large variety of stitches. There are at least twenty-two basic stitches, each with variants.

Here are a few stitches selected for their interesting structure and visual appeal.

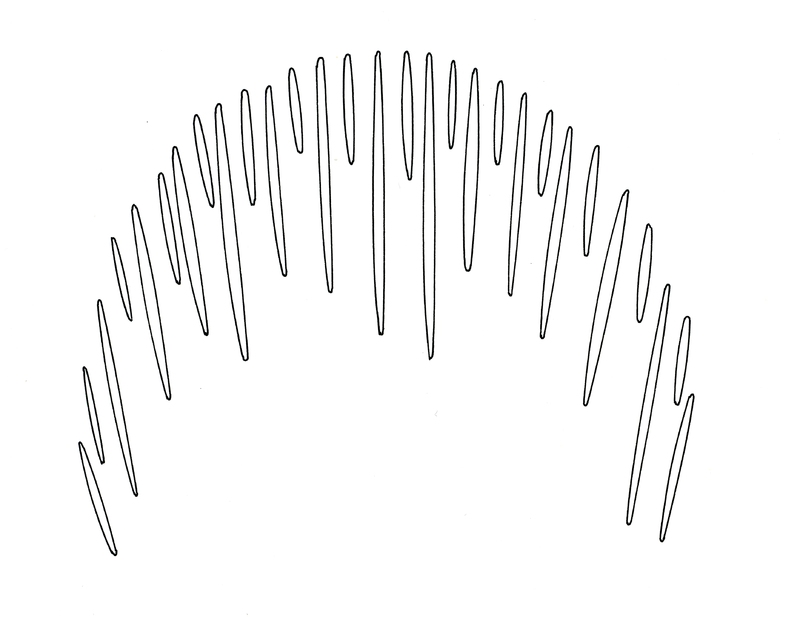

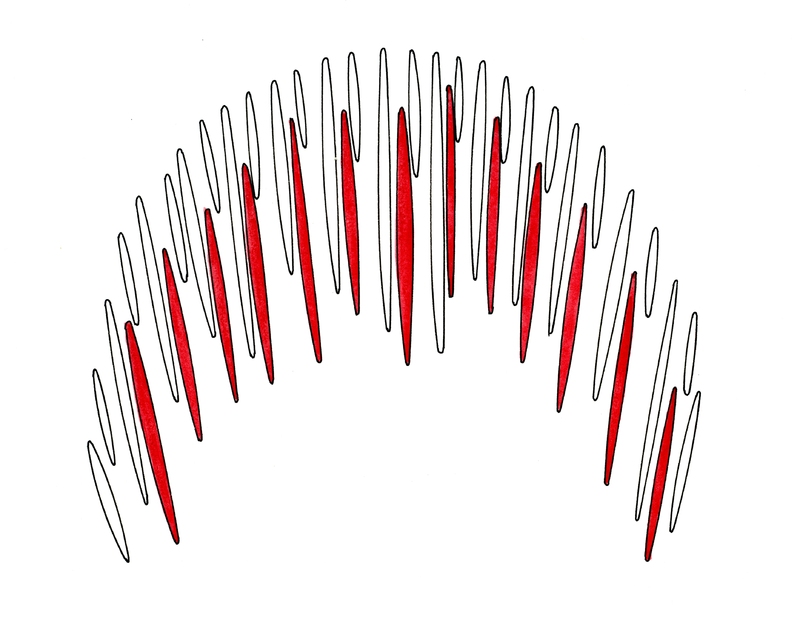

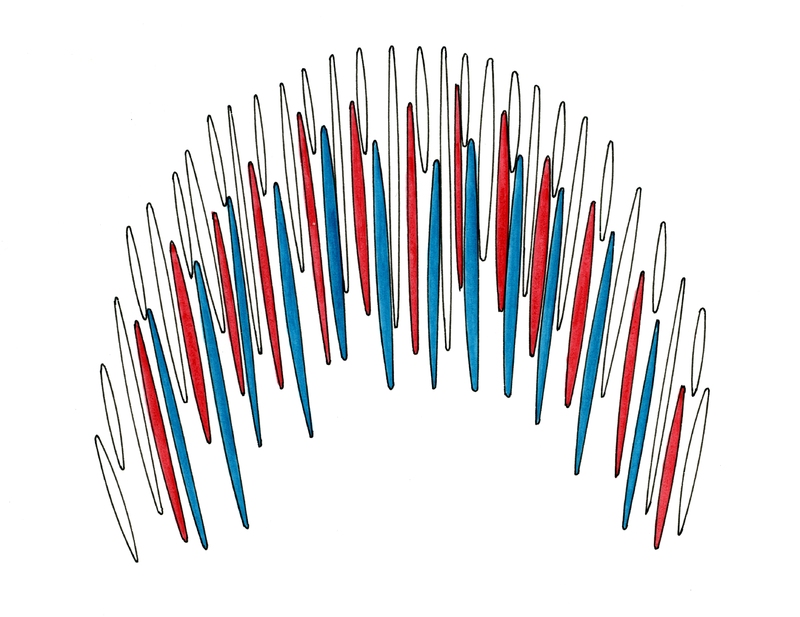

Satin stitch (taozhen 套針) shading is used in double-faced embroidery and when imitating the blending of colors in painting. This shading effect can be achieved by alternating long and short stitches or by staggering stitches to embroider flower petals or the wings of birds with minute color changes.

The shading stitches can be applied in multiple subsequent rows of stitches in variable length (santaozhen 散套針), building up layers of stitches as can be seen on the rocks in the illustration.

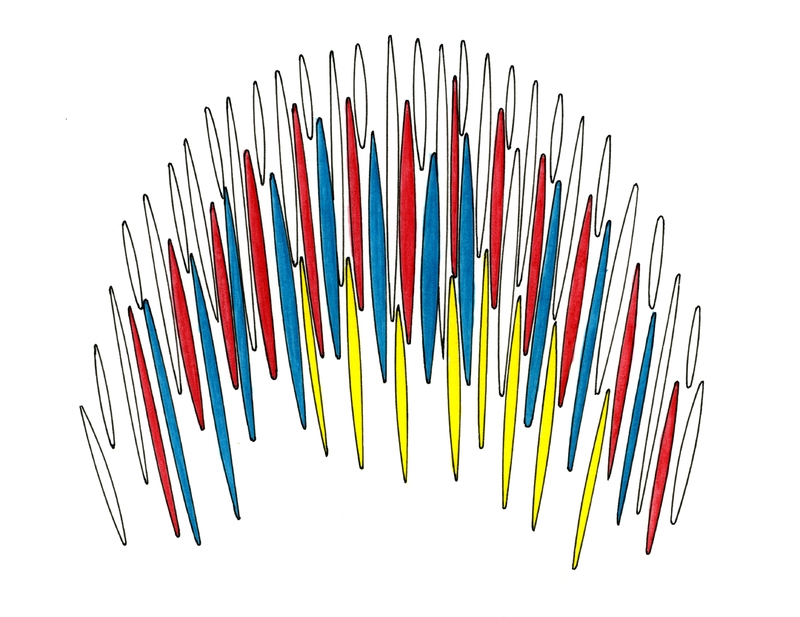

Seed stitch (dazixiu 打籽秀) or Peking knot (also known as the “forbidden stitch” or “blind stitch”)

The seed stitch is somewhat time consuming to create but gives the embroidered area a three-dimensional relief appearance in which the individual stitch is hardly detectable. The seed stitch was used for the bodies of the dragon and phoenix among other areas in this pair of sleeve bands.

Peking stitch (Beijing zhen北京針)

The Peking stitch is used to outline or fill an area. It is produced in two steps, when using one needle: First a row back stitches (also commonly used for plain outlines) is worked, then a thread is woven through the individual running stitches with looping either above (as shown here) or below the back-stitch row. The stitch can be worked with two threading needles, the first for the back-stitch, and the second one for the loops.

The arts of kesi tapestry weave and embroidery

The splendor of the Chinese textiles in Gertrude Bass Warner’s collection is greatly enhanced by two techniques that we find at times combined in a textile. The first technique is the marvelous complex silk-slit (kesi 緙絲; in older texts and Gertrude Bass Warner's correspondence, transcribed as k'o-szu) tapestry weave that their makers employed to represent pictorial content and even calligraphy. The second technique is the masterly execution of embroidery, which was less expensive in the production process but no less complex.

Kesi, which is also called “silk tapestry weaving” (as opposed to Central Asian wool tapestry weaving), “incised silk” or “carved silk,” because the colored weft threads form the pattern and its outline, appears as if the weft was cut off although it is returned, instead of passing through the entire shed to the selvage.

Kesi is a pictorial weave emulating painting or embroidery. Regular tapestry weaving had been in use in China since the Tang dynasty (618-907), but it was in the Song dynasty (960-1279) that Chinese weavers adopted the kesi technique from Uyghur and other weavers who worked for the Liao (907-1125) and Jin (1115-1234) dynasties, then China’s political adversaries to the north.

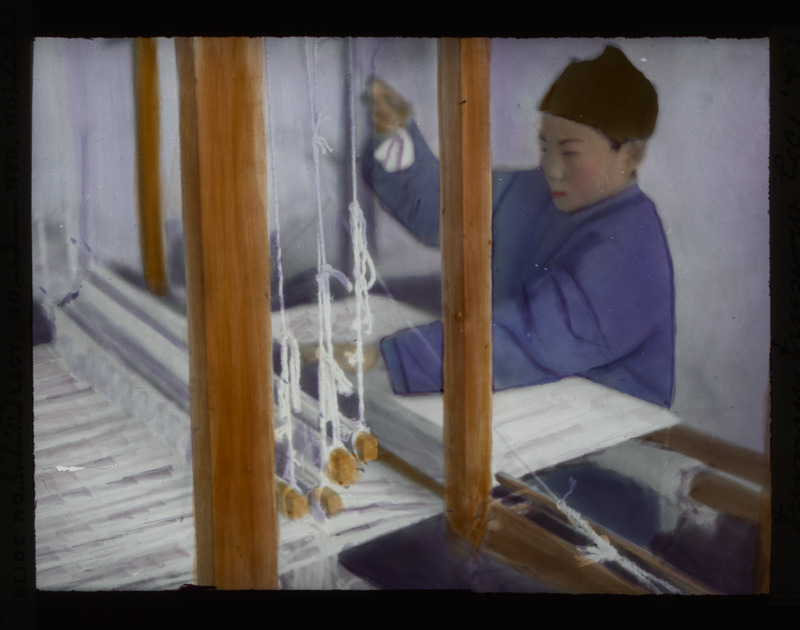

The Song artisans began to imitate painted imagery in their refined silk fabrics that—when viewed from a distance—appeared like paintings of ink and color on silk. To achieve this marvelous result, the pattern was sketched on paper and placed beneath the warp threads. While looking through the warp threads the weaver traced the pattern with a brush and thus transferred it onto the warp. It could then be executed with shuttles in the desired color.[1] The decision made by Song Emperor Huizong (1082-1135; r. 1100-1126) to establish the Elegant Embroidery Workshop (wenxiu yuan 文繡院) at court and to include examples of kesi weaving and masterpieces of embroidery in the imperial art collection, elevated the status of both techniques from crafts to works of art. And this status was never questioned again.

The Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) which conquered the Song, made ample use of gold thread in court attire as well as in fabrics for domestic furnishings. The predilection of using gold to decorate fabric may also be linked to the influence of Uyghur weavers who had learned to weave with gold and silver threads in the fashion of Persian nasij brocades.

In the late Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasty, women’s garments began to be decorated not just with auspicious symbols but also with figures in landscapes. These scenes were usually derived from the rich theatrical repertory that had become popular since illustrated printed novels started to reach large literate audiences. This figural imagery was integrated into the visual sphere of auspicious symbols and ultimately became the preferred decoration for Chinese women’s clothing, as well as for domestic furnishings such as celebratory hangings, curtains, and furniture covers.

Popular scenes from novels and theatrical performances were published in pattern compendia creating an inventory from which Qing weavers and embroiderers could choose. These printed pattern books circulated widely among textile workers and the repetition of motifs in various media increased the recognition of specific scenes among their customers.

Like weaving, embroidery was perceived as gender-specific work, involving women of all ages, every social class and every ethnicity.[2] But while weaving constituted a household duty and economic necessity, women’s self-representation in poetry and embroidery manuals reflects their aesthetic pleasures, their personal authority derived from experience and artistic skill, their spiritual dedication, as well as their social enjoyment of the Inner Chambers—or their lonely occupation performed while lost in thought or longing for loved ones. Through embroidery and poetry (at times with embroidery as the topic), Grace Fong observes “women define and claim a specifically feminine but multivalent space in which is located the meaning of work, virtue, talent, aesthetics, and sociality.”[3] Embroidery allowed women to compete with the male literati practices of painting and composing poetry, and so they did.[4] Often the embroiderers who created fine works as a pastime (for their own wedding trousseau, as decoration for clothing or household furniture, or as gifts) remained anonymous, leaving the objects themselves as the only evidence of their meticulous training to master the eighteen common stitches required before they could apply their patience and ingenuity to their own designs.

Textile ornamentation through embroidery was not only perceived as "painting with needle and thread." Skillful drawing was the foundation, and that work was remunerated more generously than the embroidery itself. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, workshops employed professional drafters to provide outline underdrawings for embroidery patterns. Domestic embroidery designs were copied from pattern books and transferred onto fabric by embroiderers, who then chose the thread colors and preferred stiches for the various designs and textures. Thus, when rendering popular illustrations from novels and dramas into wearable “paintings,” the execution of narrative details in a single pattern could vary greatly due to the different hands at work—as seen in roundels and sleeve bands from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[5]

Even though the emerging putting-out textile production system assigned important steps to male craftsmen and relegated the garment parts and accessories that were produced in series (such as sleeve bands, collars, borders, and decorative roundels) to women, embroidery was cultivated as an art beyond the fall of the Qing dynasty. Several artists influenced embroidery to such an extent that 190 years after the invention of embroidery machines[6], which commodified the art and devalued handstitched embroidery, we still remember their names and legacy. Dorothy Ko has shown how Shen Shou (沈壽, 1874-1921), perhaps most famous among these artists, created life-like embroidered imagery (fangzhen xiu 仿真绣) and signed many works. She single-handedly “reformed traditional Suzhou style embroidery by introducing Western techniques of light and shadows borrowed from photography and oil painting”.[7] Shen was especially inspired by techniques she had studied during a two-month journey to Japan initiated and financed by Chinese Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) to foster the establishment of an up-to-date “officially sponsored embroidery school for girls…”[8]. Cixi became aware of Shen’s talent when she received embroidered screens of the Eight Immortals (Baxian shangshou 八仙上壽) and a hanging of the Buddha of Endless Life (Wuliang shoufo 無量壽佛) as a birthday gift in 1904. Because of the superb quality of her work, Shen was also supported by Zhang Jian (張謇, 1853-1926), a distinguished collector and one of the founders of the first private museum in China, the Nantong Museum, which held embroideries from Shen’s hand.[9] On her deathbed, Shen, who was illiterate, dictated her knowledge to Zhang, who recorded and published her seminal work in 1927 using her sobriquet Xuehuan (雪宦) in the title, Xuehuan’s Embroidery Treatise (Xuehuan xiupu 雪宦繡譜).[10]

At the height of Shen’s active time, embroidery had already ceased to be an exclusively female art. Ko reports that “By the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, half of the embroiderers in the Shanghai workshops were male… Suzhou boasted over 70 embroidery workshops in the 1880s, which later grew to about 150. They were subdivided into three streams: the 'workshop' (xiuzhuang 繡 or jinzhuang ), specializing in the official robes and banners for court ceremonial use; the theatrical costume workshops (xiyi hengtouye 戲衣橫頭業), which also made religious paraphernalia and garments for burial; and the 'scissor trade' (jianye 剪業), supplying such everyday goods as pillow ends, table frontals, fan cases and bed valances.”[11] Just like the weaving industry at this time, embroidery workshops subcontracted quotas to skilled local women, who were able to support their families through the resulting income and thus gained a certain level of independence.[12]

Steps of silk production

- Each silk moth lays 300 to 500 eggs, which are collected for the production of the following year.

- Silk moth eggs hatch to form larvae or caterpillars, known as silkworms.

- The larvae are fed with finely chopped mulberry leaves.

- After growing and molting several times, the silkworm extrudes a silk fiber from a gland below its breathing openings and forms a net to hold itself, attaching the fiber to straw.

- The silkworm performs movements in a ‘figure 8' shape, winding the fiber it releases around itself.

- The silk fibers solidify when exposed to air.

- Within two to three days the silkworm produces approximately 800 to 1,200 m of filament and completely encloses itself in a cocoon in about two or three days. The amount of usable quality silk in each cocoon is smaller, at each end of the fiber ca. 60 cm have to be discarded. As a result, about 2,500 silkworms are required to produce 500 g of raw silk.

- The intact cocoons are boiled, which kills the silkworm pupa.

- The outer end of the silk fiber loosens in the hot water. Several filaments (up to 48 depending on the desired thread thickness) are twisted together and reeled off the cocoons to make a silk thread of the intended weight.

- The thread, which depending on the quality of the cocoons can be up to 1,200 m long, is wound onto a bobbin which can be used to dress the loom with raw silk or can be unwound in to hanks of silk for dyeing.

Fashion

Since time immemorial garments have been the most obvious visible identifier of status. Emulating status through dress at times to the limit of affordability often became an obsession between social classes. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that intact pieces of clothing as well as fragments of fabric found during the archaeological excavations of a plethora of Chinese tombs reveal that fashionable attire was essential to members of the upper classes throughout history. Although sartorial regulations limited the use of certain fabrics, colors, and cuts, subtle—and at times significant—modifications in dress inspired by regional differences, foreign influences, and the clothing of higher social strata continuously made their way into the attire of wealthy Chinese men and women. Aside from the textiles recovered from tombs, such variations in fabric designs and clothing styles are reflected in paintings dating back hundreds of years to the beginning of the Common Era.

Since the late Ming dynasty (1368-1644), when wealthy members of the middle class and those who imitated the style of the well-to-do enjoyed investing in fashionable attire, compliance with sartorial regulations became increasingly difficult to enforce and clothing habits became quite ephemeral, while new details in dress developed into fashionable trends. The complaints by conservative officials that both, the wealthy and those less affluent—and especially the women—overstepped the boundaries of the traditional canon of clothing cut and ornamentation, indicate that the obsession with fashion could not be contained.

Illustrated woodblock-printed novels that were widely consumed by the literate, and public and private theatrical performances enjoyed by both literate and illiterate audiences, inspired the decoration of women’s outer garments from the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) with a great variety of theatrical performance scenes on the front and back as well as on collars, sleeves, sleeve bands, and borders. Urban courtesans acted simultaneously as models, advertising agents, and arbiters of fashion when their stylish attire helped to distribute this new kind of décor. Whether genteel ladies, wealthy women from merchant families, or even women of the lower classes commissioned or bought and wore such outer garments in public probably depended upon where on the scale they fell between observing sartorial regulations and strict Confucian morals at one extreme and eagerness for social advancement on the other. Strict families who followed probity regulations for the instruction of clan members (jiaxun 家訓) probably preferred more simple and restrained patterns, while women who aimed to present themselves as ‘modern’ and ‘fashionable’ were more likely to wear attire inspired by stylish courtesans, despite the risk of being criticized for profligate consumption. The same level of strict family culture probably determined whether women traveled (possibly in the company of male family members) to scenic spots, such as famous gardens, religious ceremonies and temple fairs, where one could see and be seen, or whether they received their inspiration from ‘proxy travel’ by reading books and viewing paintings or illustrations in local gazetteers of popular destinations and their fashionable visitors. Either way, if they could afford it, Qing women had the opportunity to wear their memories or their dreams of travel embroidered onto a jacket.[13]

Professional weavers and embroiderers working in commercial or domestic workshops emulated semi-formal products made in the imperial workshops as well as garments made for the theater.[14] They translated these textiles into fashionable secular clothing for women and children and decorated them with the familiar auspicious symbols as well as the new fashionable narrative imagery.

Examples of such textiles from the collection of Gertrude Bass Warner show how the canon of weaves, color combinations, and decorative trimmings enhanced the choices women made when they invested in new outfits for themselves and their offspring. They could choose between key theatrical scenes of a drama (zhezi xi 折子戲) or “just an assemblage of vignettes”[15] derived from popular contemporary plays (chuanqi 傳奇), storytelling (tanci 彈詞-), or non-operatic arias (sanqu 散曲).[16]

Manchu Woman's Nonofficial Formal Coat with Lantern Roundel and Wave Design

Full-length garment, front overlap closing to right, fastened with five loop and gilt-metal toggle buttons, wide sleeves ending with flared cuffs.

Chinese Woman's Nonofficial Semiformal Paired Skirts (Qunzi) with Floral and Butterfly Design

Green silk tabby embroidered with multicolored silk floss; each apron section has straight end panels and twelve gores, attached to band.

Sleeve bands, collars and roundels

Decorative elements in Chinese fashionable textiles were produced in modules: sleeve bands, collars, and roundels were adorned with embroidered decor and could be individually commissioned or selected from finished pieces in commercial embroidery workshops when a jacket was ordered. These workshops had embroiderers working in house, but often sub-contracted work to embroiderers who worked in their own homes and contributed their income to the household or created personal savings.[17] Embroidered roundels were produced as appliqué patches. Collars and sleeves were the parts of a garment most commonly exposed to wear and tear. Sleeve cuffs were therefore protected with exchangeable sleeve bands of various designs as requested by the patron, ‘dictated’ by latest fashion, or left to the embroiderer’s imagination. Sleeve bands could carry auspicious symbols, present visual puns or scenes from popular stories, or show simple geometric patterns. Some show identical decor on the right and left sleeves, some have complementary designs, while others are arranged as mirror-images with symmetrical patterns.

Pair of Sleeve Bands with Squirrels and Grape Vine Design

Squirrels (songshu 松鼠), which reproduce quickly, and grapes (putao 葡萄), which hang from the vines in clusters, represent the wish for many generations of sons and grandsons. The designs on this pair of sleeve bands are symmetrical mirror-images.

Rebus: Songshu putao 松鼠葡萄 May you have many sons and grandsons!

Pair of Sleeve Bands with Monkeys in Landscape Design

This pair of sleeve bands conveys the jacket wearer’s wish for an auspicious future. The designs are symmetrical mirror-images.

A monkey, pronounced hou 猴is a homonym for hou 侯, the noble rank of a marquis. While sitting on the branch of a pine tree (a symbol of longevity and friendship), the monkey catches a butterfly. Beneath it hangs a bag (dai 袋) for an official seal. A second monkey sits beneath a peach tree, holding a peach (shoutao 壽桃), a symbol of immortality, while bats (fu 蝠) fly in the sky. Together this can be read as a wish for longevity (shou 壽), blessings (fu 福) and for a husband’s (or son’s) successful career as an official.

Rebuses:

Fenghou guayin 封侯掛印 May you receive the rank of Marquis and be given the seal of office!

Fushou shuangquan 福壽雙全 May you be blessed with a long life and wealth!

Pair of Sleeve Bands with Patterned Gourd, Butterfly and Insect Design

Butterflies (hudie 蝴蝶) are homophonous with fu 富, wealth, and die 疊 means to pile up, while the gourd gua 瓜 is a plant that produces many fruits from a single vine, and crickets survive long dormant periods before they re-emerge from the soil, symbolizing long life. Dragonflies (qingting 蜻蜓) stand for purity qing 清and celebration qing 慶, praying mantises are seen as being patient and agile fighters.

The embroidery of this pair of sleeve bands is exceptional for the great variation in the abstract patterning of the gourds.

Rebus: Guadie mianmian 瓜瓞綿綿 May you be blessed with many generations of descendants!

May you experience wealth, many descendants, and a long joyful life!

Pair of Sleeve Bands with Women in Garden Design

This pair of sleeve bands shows each two scenes of women’s entertainments in a garden setting. In the upper section of the left sleeve band one woman has dropped her fan, possibly while waving to greet someone, while another is shown fishing in the water below. The right sleeve band shows a woman at the top playing a pipa (lute), while another listens to the music while leaning on a rock and observing two rabbits at play. These two sleeve bands show different landscape features: on the left is a garden landscape dominated by water, with a gate as an architectural element, and a palm tree and butterflies; while the right sleeve band shows a pagoda next to a pine tree in a more distant landscape. The embroidery of this pair is extremely rich in terms of patterns and color variation and was excuted with attention to fine details: all four women have elaborate coiffeurs, wear delicate jewelry and beguiling smiles.

Theater robe

The right lapel and the front and back lower borders of this theatrical performer’s jacket show thirteen scenes from the folktale The White Snake (Baishe zhuan 白蛇傳) framing the colorful embroidery of the main sections. The front and back panels as well as the shoulders and backs of the sleeves are decorated with kesi-tapestry roundels with scenes from a dramatic adaptation of the eighteenth-century novel Dream of the Red Chamber (Hongloumeng 紅樓夢). Each carefully composed scene features two of the protagonists in a garden landscape replete with plants, trees, and architectural structures. This kind of popular imagery taken from prints and plays made its way into fashionable attire commissioned by women of means in the nineteenth century and inspired the creation of ever more elaborate embroidered roundels[18] and borders.[19]

Manchu ceremonial attire

The dragon robes in the collection of Gertrude Bass Warner were produced for members of the Qing court. The Manchu emperors and their officials followed the traditional Han-Chinese distinction between official and non-officials clothing, in which official garments were reserved for court attire and outfits worn for government functions, and non-official clothing was to be worn during family celebrations and seasonal festivals that included public appearances.

The Manchu emperors also followed their Chinese predecessors in the categorization of the level of formality for Manchu ceremonial garments, distinguishing three levels of formal (chaofu 朝服), semi-formal (jifu 祭服) and informal (changfu 常服) costumes.[20]

Formal costumes included all garments designed for ritual ceremonies, semi-formal attire was worn by the court officials for all official court functions and government related events, and informal costume was quotidian clothing.

Han-Chinese weavers in the imperial workshops had been trained to weave the individual parts of a garment within the length and width of a bolt of silk such that they achieved an optimal distribution that avoided any waste of the precious fabric during tailoring, a technique called ‘weaving into shape,’ while Manchu garments derived their shape from animal hides, a holdover from the semi-nomadic life in the forests and steppe of their landscape of origin.[21] The trapezoidal form of the Manchu robes with their wide base left more fabric waste.

References

[1] Kuhn, Dieter (ed.), Chinese Silks. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012, 524; Gao Hanyu, Chinese Textile Designs. London: Viking Press 1992, 21.

[2] Grace Fong has contextualized poetry on weaving and embroidery as well as manuals and illustrated treatises on embroidery by women in her seminal article “Female Hands: Embroidery as a Knowledge Field in Women’s Everyday Life in Late Imperial and Early Republican China”, Late Imperial China, Vol. 25, Number 1, June 2004, 12. DOI: https://doi.org./10.1353/late.2004.0007; accessed 12/14/2018.

[3] Fong (2004), 13.

[4] One early female master of the art, Han Ximeng (韓希孟, fl. 1634), created an album of eight embroideries in which she ‘traced and copied’ masterworks of Song and Yuan painting – a process undertaken by male students when learning how to paint – gained recognition from the eminent art critic Dong Qichang (董其昌, 1555-1636) for the resemblance of her works to master literati paintings. Dorothy Ko, “Between the Boudoir and the Global Market: Shen Shou, Embroidery, and Modernity at the Turn of the Twentieth Century”, in: Jennifer Purtle and Hans Bjarne Thomson (eds.), Looking Modern. East Asian Visual Culture from Treaty Ports to World War II. Chicago: Center for the Art of East Asia. Art Media Resources, Chicago: 2009, 41.

[5] Rachel Silberstein has described the “democratization” of dress at this time, when “celebratory and ceremonial styles that had once been confined to imperial or noble circles, became more accessible to wider audiences.” (Rachel Silberstein, “Fashionable Figures: Narrative Roundels and Narrative Borders in Nineteenth-Century Han Chinese Women’s Dress,” in: Costume, 01/2016, Vol.50 (1), 65.)

[6] http://www.ahey-embroidery.com/A-Brief-History-of-Machine-Embroidery.htm; accessed 04/26/2019. The first embroidery machine was created in 1828 by Joshua Heilmann of Mulhouse, France. This hand-embroidery machine could utilize up to four hand-embroiderers. The next step towards fully mechanized embroidery was the ’Schiffli-Machine’of 1863. Its shuttle resembles a sailboat, a little ship or ‘Schiffli’ in Swiss German. It was created in Switzerland by Isaac Groebli, who used a continuously threaded needle and a shuttle containing a bobbin of thread to create the embroidery design in backstitch. Groebli’s oldest son later refined the machine and built the first automatic Schiffli machine, which was transformed into the first embroidery sewing machine that used six heads and revolutionized the embroidery process in 1911 – the very year that the Qing empire fell and with it the imperial textile workshops.

[7] Ko (2009), 38.

[8] Ko (2009), 45.

[9] On the first museum of China see the seminal article by Lisa Claypool, “Zhang Jian and China’s First Museum”, in: The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 64, No.3 (Aug. 2005), 567-604.

[10] Chen Juanjuan and Huang Nengfu, “Textile Art of the Qing Dynasty”, in Kuhn, Dieter (ed.), Chinese Silks. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012, 477.

[11] Ko (2009), 42. Ko quotes Xu Weinan, Guxiu kao 顧繡考 (Examining Gu-style Embroidery), Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju 1936; and Lin Xidan 林 ,Suzhou cixiu 蘇州刺繡 (Suzhou Embroidery). Suzhou: Suzhou daxue chubanshe, 2004), two works that were not accessible to me at this time. Ko (2009), 56, fn. 14.

[12] Before the Great Depression of the 1930s Suzhou workshops employed over 24,000 embroiderers (Ko, 2009, 53). This production system declined as factories with mechanized looms and embroidery machines increasingly took over in the 1930s.

[13] Rachel Silberstein, “Eight Scenes of Suzhou: Landscape Embroidery, Urban Courtesans, and Nineteenth-Century Chinese Women’s Fashions”, in: Late Imperial China, 2015, Vol. 36 (1), 1-52.

[14] Sarah Dauncey describes how competitiveness among women spurred sartorial transgressions in the Late Ming. Sarah Dauncey, “Illusions of Grandeur: Perceptions of Status and Wealth in Late Ming Female Clothing and Ornamentation”, in: East Asian History, Number 25/26, June/December 2003, 43-68.

[15] Li Yuhang, “Representing Theatricality on Textiles”, in: Zeitlin, Judith and Yuhang Li, Performing Images. Opera in Chinese Visual Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2014, 76.

[16] Li (2014), 77.

[17] Dorothy Ko, “Between the Boudoir and the Global Market: Shen Shou and Suzhou Embroidery at the Turn of the Twentieth century”, in: Jennifer Purtle and Hans Bjarn Thomsen (eds.), Looking Modern: East Asian visual culture from treaty ports to World War II. Chicago: Chicago Center for the Art of East Asia. University of Chicago, 2009, 53.

[18] This robe has been documented in great detail in the catalogue edited by Judith T. Zeitlin and Yuhuang Li, Performing Images. Opera in Chinese Visual Culture. Smart Museum of Art. The University of Chicago 2014, 76-77, 162-166 (Cat. no. 28).

[19] For more about the changes in fashion at the end of the Qing see Silberstein, Rachel, “Fashionable Figures: Narrative Roundels and Narrative Borders in Nineteenth-Century Han Chinese Women’s Dress”, in: Costume, 01/2016, Vol.50(1), 63-89.

[20] John E. Vollmer, Decoding Dragons: Status Garments in Ch’ing Dynasty China. Eugene: Museum of Art. University of Oregon 1983, 24-32.

[19] Vollmer (1983), 18-19.