<p>This striking embroidery is emblazoned with the images of the Eight Daoist Immortals, from right to left: Han Xiangzi, Cao Gaojiu, Lan Caihe, and Li Tieguai, with Shoulao, the God of Longevity (not one of the Eight Immortals) in the center, then continuing on the left with Zhang Guolao, Zhongli Quan, Lü Dongbin, and He Xian’gu (the only female immortal in the group). Confusingly, the (later) handwritten labels attached to the top of the textile misidentify many of these figures, whose individual stories are provided below.</p>

<p>Han Xiangzi (韓湘子), also called Philosopher Han, is said to have been the nephew of the famous ninth-century poet Han Yü (韓瑜). He is the patron of musicians and carries a flute, which is said to have the magical power of calming wild animals.</p>

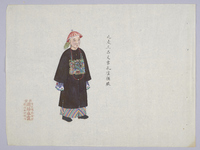

<p>Cao Gaojiu (曹國舅) is shown with castanets, which reference the ‘passport’ that allowed him access to the imperial palace, a privilege that he held in life since he was the brother-in-law of the tenth-century Emperor Renzong. Due to his elevated status, Cao is always depicted wearing court attire. He is revered as the patron of actors.</p>

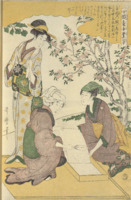

<p>Lan Caihe (藍菜和), the patron of florists and gardeners, carries a basket with flowers reminding people of the brevity of life. Lan’s gender is uncertain since s/he is sometimes depicted as a young girl or boy.</p>

<p>Li Tieguai (李鐵拐) can easily be identified by his iron crutch. He is said to have mastered the magic of temporarily letting his soul leave his body. Once while his soul was away, someone saw Li’s seemingly lifeless body and had it cremated. When Li’s soul returned, his body was gone and so his soul chose instead to reanimate the body of a lame beggar. Li is often shown wearing a double gourd in which he carries medicine. He is the patron of the weak and sick.</p>

<p>Although not technically one of the Eight Immortals, the God of Longevity Shoulao (壽老) is usually depicted as a bearded old gentleman with an elongated bald head surrounded by auspicious motifs such as deer, cranes, bats, peaches, and <em>lingzhi</em> mushrooms. He is featured in the center of this textile in a walled garden wearing a rode emblazoned with stylized <em>shou</em> (longevity) characters and holding a peach of immortality. The deer to his right is shown eating a magic mushroom.</p>

<p>Zhang Guolao (張果老), the patron of painters and calligraphers, is shown carrying a long slender percussion instrument (a “fish-drum”) with two sticks, which is said to cure illness. Often Zhang is shown riding a magical white mule, which he could miraculously shrink and put in his pocket. When needed again, he would take the mule out and sprinkle water on it, whereupon it would grow back to full size.</p>

<p>Zhongli Quan (鐘離權) was a general said to live during the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE). After being defeated by the Tibetan army, he escaped into the mountains. There, he met a hermit who taught him about alchemy before sending him back to the world to do good using a magical fan that could turn stones into gold and bring the dead back to life. Zhongli used the fan to help many people who were in distress. He is usually depicted with a feathered fan and a peach and accompanied by a crane. He is said to have been the teacher of Lü Dongbin.</p>

<p>Lü Dongbin (呂洞賓) was a Tang poet and the patriarch of the Complete Perfection school (Quanzhen 全真) of Daoism. He is said to protect scholars and warriors and is usually depicted with a sword to dispel evil spirits.</p>

<p>He Xian’gu (何仙姑) is the only female in the group of eight immortals. She lived in the seventh century and is said to have become immortal after consuming a peach of immortality. She is often shown holding a lotus flower, a symbol of purity, and a <em>sheng</em> (a wind instrument with vertical pipes) and is sometimes accompanied by a phoenix.</p>

Escape from Peking/three Japanese letters, handwritten notes.

Transcript:

Escape from Peking on Nov. 9, 1924

Admiral Oriental Line

Managing Operators U.S. Shipping Board

SS “President McKinley”

Mrs Boyd Carpenter & I have the stateroom. Mrs Scalia [?] & Mrs Potter are in a section in the open car.

9 A.M.

As we sit here in one car on the train, we not only hear the guns that are fired from Tientsin—we feel the explosion.

Mrs Scalia has started off alone on foot to see if she can get a man at the the railway station to [illegible] our baggage & to try to find out if we can go directly onto our steamer. The station is some miles & a half away. If we would leave the trunks behind we could all walk with her but of course I will not leave the Museum things behind with no one to look after them.

10 A.M.

Before leaving Peking we sent a telegram to the Astor House Hotel in Tientsin asking for rooms. They have sent their porter with an automobile & two assistants to look after the baggage. Leaving the train, as one passed the engine I [illegible] to take another picture of it. There were some British soldiers nearby. I asked them to come close that they could be included in the picture. All the British soldiers still guarding the train, came. Having taken the picture & thanks them for their faithfulness & protection we went on our way rejoicing. We had come the 80 miles in 31 ½ hours. No one had been hurt.

In the office of the American Express Co. we found Mrs Scalia. She reached the railway & train just as Marshal Wu [Wu Peifu of the Zhili Clique] with some 600 of his followers were leaving by train for the coast, there to take a ship for Tsingtau [Tsingtao/Qingdao]. His army was left in the lurch, no food, no shelter, no money & and most of them are a long way from home. With everything to lose & nothing to gain how can they be induced to join the army?

And speaking of fighting, one of Marshal Wu’s officers did refuse to fight. He was decapitated there in the station just as Mrs Scalia arrived. His head was placed on a spike for all to gaze upon. It was pandemonium let loose, in that station, and a body blow to my siding with the Wu faction. It reminds me of midaeval [sic] Europe.

Dear old China. This is the 5th revolution in eight years. May it be the last.

----

1

from Peking

Our escape with our treasure for the Univ of Oregon Museum

Indochina S.N. Coy. Ld.

I have written you how difficult it was to reach Peking from Tientsin because Chang So-lin [Chang Tso-lin/Zhang Zuolin of the Fengtian Clique] was moving his army and his supplies—getting ready to attack the government.

We were glad to find room at the Hotel des Wagons Lits because it is in the legation quarter and just across the street is one of the embassies & our American Legation so we could always give the flag just inside the entrance a silent greeting.

While Chang Tso-lin was preparing to attack the government forces, with the object of moving on to Peking, General Feng—the Christian general [Feng Yü-hsiang/Feng Yuxiang]—was given the task of blocking him.

We reached Peking in the midst of the preparations. Automobiles, horses, mules, carts, everything in sight was commandeered, including the men who drove them.

Our rickshaw coolies requested American flags to place on our rickshaws to protect them and us. Every foreigner flew his flag on anything and everything that belonged to him, as a warning to the recruiting officers to keep their hands off.

General Munthe’s guards, the Chinese protection for the Legation Quarter, patrolled the southern [illegible] of the city in groups of five.

When General Feng’s army left, there was a sigh of relief. But about this time the Chinese merchants began to consider what would happen if General Feng’s army should be defeated—and trunks, boxes, baskets—chests of drawers—every conceivable kind of receptacle, was filled with merchandise & taken to the sheltering wings of some foreign friend in the Legation Quarter. Simultaneously the Chinese began to send their women & children to our hotel for refuge.

Our first realization that the supplies were low came when the marmalade—which is a part of every Englishman’s breakfast—gave out, then the butter. Lard was substituted. Also altho the cold weather had set in, our hotel was not heated. We wore our winter coats in our rooms.

Then, two weeks ago, on Nov. 6th, as I sat in the lobby of our hotel waiting for Mrs White—the Princess der Ling—Dr Ferguson came in, “Where are you going” “On an errand outside the city wall with Mrs White” “Don’t you go. The city was capture last night by Feng’s troops. Railroads, telegraph, telephone have been stopped—and the city is guarded in sections so that no one shall get away.” “But General Feng?” I asked. “He has deserted the government and joined forces with Chang-Tso-ling [sic]. Stay in the Legation Quarter.”

He waited until I had promised.

Wem as well as the Chinese—were considering the possibility of Chang-Tso-lin’s soldiers looting the city and were starting to gather in our Museum things to be packed. Mrs. White & I were going to a Chinese tailor in the Chinese city, outside the walls of the Mandarin, or Imperial city, where I had left an imperial coat, brought from collection at home, to be made up. In the case of looting, everything in the shop including that could would be lost.

Mrs White felt that she, a Manchu princess, could go where she liked, & [illegible] into her car. She went a block, as far as the city gate, & was turned back.

We were quite short of funds, & not knowing what might be ahead of us. I went to the International Bank—located in the Legation Quarter—for money.

The Chinese, fearing that the government paper money might become invalid—were making a run on all the banks, demanding silver in the place of their paper money. The Chinese banks promptly closed their doors. In the enclosed section, set-aside for their Chinese depositors in the International Bank, there was a seething mass of people all calling at once to attract the attention of the clerks & get their paper money changed to silver. The young woman who waited on me said they would not have to close their doors, as they had millions in their vaults.

In the meantime, Mrs Scalia & Mrs Potter had taken the bit in their teeth & gone in another direction for the porcelains that I had left with the dealer to be packed. Two [illegible] brought them all back to our hotel. The Legation Quarter is the safest part of the city. It is guarded from the inside by the marines from all the Legations—and from without, so we thought, by Gen. Munthe’s troops. But no, when the city was captured the Chinese guards were incarcerated & only allowed to go out one at a time after swearing allegiance to their captors.

General Feng said he would maintain order & there should be no looting. Two would be looters were promptly decapitated & their heads, each in its box was exposed at the city gate as a warning.

The city was hermetically sealed—no one could go in or out of the city on that day. No [illegible], no telegraphy, no telephone, no mail—it was hermetically sealed except for one means of communication. Our American Legation has a wireless & sent word of our plight to the world.

The President of the Republic was under guard in his palace. One official was locked in the cellar of Gen. Feng’s house, being held for a ransom. The rest of the officials of the old government came into the Legation Quarter, where they were—by treaty—immune. They flocked into the Hotel des Wagons Lits until every available nook & corner was taken. Some of them came down to the dining-room for their meals but most of them, considering discretion the better part of valour, staid in hiding in their rooms. The halls & stairs were crowded with Chinese children, as many girls as boys, I was happy to see.

When, in Tokyo, we talked over the pros and cons of coming to Peking with J. Ballontine [?], our Vice-Consul he said it would be safe to go to Peking, because it would always be possible to get away. According to our treaty the railroad between the Capital & the sea must be kept open.

The diplomatic body was called together. The nationals from each country were carefully [illegible]. There were 1300 Americans who might have to be taken with our Legation if the government side should say to Gen. Feng, “No you don’t,” and there should be a fight in within the city.

After a few days our International train was sent up from Tientsin, with 200 guards, mail & reinforcement of soldiers for the Legations. The train arrived at eight o’clock, started back two hours later. Draped over the front of the engine was “old glory” & on the sides the English, French & Japanese flags.

The train reached Tientsin safely. Once it came up and returned at night, we thought that we would go on the 2nd but Dr Ferguson was opposed. He said “you may get there and again you may be turned back. There is fighting all along the track. If you are turned back you will have lost your places in this hotel in the Legation Quarters. We could take you in, but how about Mrs Scalia & Mrs Potter?”

There is a shortage of fuel and food in Peking. The Fergusons had changed their way of living so that if necessary they could get along with one fire, beside the one in the kitchen. Their coal on hand would only allow that much—(In Peking there are no furnaces, the rooms are heated by little iron stoves.)

General Feng is in league with Soviet Russia. The Soviet government has established itself not in a Legation like the other foreign powers, but in an Embassy, in the Legation Quarter. An ambassador takes precedence over a minister, and the situation is full of possibilities.

The government party did say “No you don’t” to General Feng, & Marshal Wu’s army was started for Peking.

Once General Feng left the city, this time to fight his old chief. We watched the soldiers as they marched out through the city gate. They were singing our hymns.

At this juncture the Belgian Minister was ordered transferred to another post. The International train was again sent from Tientsin to fetch him his wife and their belongings as far as Tientsin.

We decided that presence would be brought to bear to get that [illegible] [illegible] and we would go. It arrived Saturday night at 7:30 and left at 4 A.M. Sunday morning.

To go on the International train it was necessary to go to our Legation, armed with passports, each personally making the request. There should be no question as to who went aboard. We were each given a permit to go on the train. The new government was very much on the alert to see that no members of the old government should get away in disguise.

In order to make sure of our places, we went aboard the night before. Shortly after the train came in.

There was a car for the Belgian Minister, one American car, two British cars, a dining car, a baggage car, and four cars for the guards. The French Capt. Bertrand in command. The cars were not heated. The temperature was considerably below freezing—we could see our breath.

Our trunks being safely in the baggage car, we found Mrs Boyd-Carpenter in the American car. Her husband professor of International law teaches in one of the Universities in Peking. She and I occupied a compartment while Mrs Scalia and Mrs Potter had a section in the open car. It was a 2nd class car. The seats covered with leather, without padding or springs—no sleeping accommodations.

French soldiers both from France and [illegible], Tommie guns in hand, kept going back and forth all the night.

It had been expected that Marshall Wu’s forces would push Gen. Feng’s closer & closer to the city until he would be forced to take refuge inside the city walls. Then when coal & food gave out, the city would surrender.

We went very slowly—a detached engine ahead, with English marines aboard, looking for bombs and derailed tracks.

At 9 A.M. we came to the first trenches. Three long zigzag trenches, some distance apart, running at right angles with our track. There was no sign of life in any of them. That meant that Feng’s forces, that left Peking to fight Marshall Wu, were advancing, not retreating. We crept along. The country was absolutely deserted. At the little stations, a few soldiers and a few camels carrying supplies. Suddenly clack clack clack clack—the advance engine was being fired upon as a notice to stop. A long wait, then a slow advance until fired upon again. The International train was not expected, and the soldiers did not know what to make of the foreign flags flying so independently over the engines.

After a couple of these unpleasant experiences, our engineer, Chinese, refused to get up from his prostrate position & man the engine, but one of our American officers took his place. A fusillade, a long stop. We were informed that there were sand bags on the track ahead. A request from us that they should be removed met the response that if we wished to go forward, we could go with the firing line and remove them ourselves—which our soldiers eventually did.

Feng’s soldiers had red badges with a white disk on the left arm. Long lines of them marching with an encircling movement, in the same direction that we were going, made us think that they were encircling Wu’s forces.

There was a sudden stop. A detached rail ahead. All hands got out to “look see”. The Jonnies pushed it back into place very quickly.

Finally we came to the outposts of Feng’s forces—instead of trenches, round holes with a man or two in each, just their heads and guns showing.

The danger seemed over. The reconnoitering engine was switched off, and we went on a little faster, much relieved.

Not having slept the night before, I was indulging in a nap when suddenly roused by Mrs Potter. “Gertrude they are firing on us with a machine gun.” Bum bum bum bum—it seemed to last a long time, but perhaps it was not more than a couple of minutes. We were ordered onto the floor by the French Commandant. It was Wu’s men. There being no reconnoitering engine ahead of us, the gun was aimed at our engine from the machine gun on the track ahead. The glass in the engine now was broken. The bullets whizzed past our coaches. We were near Tientsin. Marshall Wu’s men had made a quick retreat, Of course they took us for the enemy. They apologized.

Our train was unable to reach the city because of congested tracks. So we spent a second night on the train. Captain Bertrand, with a couple of aids [sic] went for help. He feared that Gen. Feng’s men would follow on the heels of Marshall Wu’s retreating forces & as one of our boys expressed it—“clean us up.”

Many of the soldiers left the train.

The men passengers put their hand baggage on the seats, and walked the mile or so to the station.

We would not leave our baggage—those precious Museum treasures—so the little group of six women and such of the guards as had stood by, spent the night in watchful waiting.

The next morning Mrs Scalia started on foot for the station in search of a [illegible] to carry our baggage.

Mrs Potter & I staid on the train to be with it—I was going to say—to guard it.

Before leaving Peking we had telegraphed to the Astor House Hotel at Tientsin for rooms. About an hour after Mrs Scalia left, who should come asking but the hotel porter & his assistants. The assistants got into the baggage car to stay with the trunks until they could be taken out, while the porter took us to the automobile.

Passing our engine on the way, I stopped to take another picture of it. Nearby were some British soldiers. I asked them to come close so that they would be included in the picture. All the British soldiers still guarding the train came. Having taken the picture & thanked them for their faithfulness & protection we went on our way rejoicing. We had come the 80 miles in 31 ½ hours. Altho shells had passed above & beneath us, no one had been hurt.

At the office of the American Express Co. we found Mrs Scalia. She had reached the railway station just as Marshal Wu with some 600 of his followers were leaving by train for the coast there to take a ship for Tsingtau. His army was left in the lurch—no food—no shelter—no money & most of them a long way from home. With everything to lose & nothing to gain how can they be induced to join the army.

And speaking of fighting—one of Marshal Wu’s officers did refuse to fight. He was decapitated there in the station just as Mrs Scalia arrived. His head was placed on a spike for all to behold. It was pandemonium let loose in that station. And Marshal Wu’s last-act was a body blow to my siding with the Wu faction. It makes me think of the conditions in Medeaval [sic] Europe.

Dear old China. This is her fifth revolution in eight years. Somehow she will find a solution to her problem and settle down in peace. We all hope soon.

Gertrude Bass Warner

Correspondence/diary

End of transcript.

Transcribed by Tom Fischer.