Collectors and tengu

If foxes are a nod to senjafuda’s historical roots in Inari worship, tengu are a nod toward a more legendary aspect of senjafuda history. In fact, tengu are probably the yōkai most intimately related to the history and self-conception of senjafuda practice, athough just how this is true is not always obvious to the untrained eye. It has to do with one of the most significant figures in senjafuda history, a man named Hagino Kinai Nobutoshi, but known in senjafuda circles as Tengu Kōhei.

Tengu Kōhei was an 18th century samurai, and was said to have been born in either 1707 or 1717, which would put him at either 90 or 100 years of age at his death in 1817. A number of early accounts of senjafuda credit him with popularizing the practice beginning in the 1750s, when his lord sent him on a pilgrimage on behalf of his younger brother, who had smallpox. Historians such as Takiguchi Masaya suggest that, based on contemporary records, there were others who were more active than Tengu Kōhei was in this period, but it’s he who got celebrated later as the key figure in 18th century senjafuda. This might have been due to his social class: as a samurai, acting at first in an official capacity, he would have lent an air of official respectability to a pastime that ran afoul of officialdom on more than one occasion.

Tengu Kōhei came to be of such talismanic significance to later practitioners that the anniversary of his death, April 1, came to be observed with special rites at the temple where he was buried. He is depicted in numerous later senjafuda, such as this large, handsome 8-slip composition. We see Tengu Kōhei depicted as a dignified old man, his white hair and beard more than a little reminiscent of the okina mask used in noh to represent an old man and a god. He is dressed for travel, suggesting we’re seeing him on one of his numerous pilgrimages, and he holds a box for his senjafuda and the distinctive pole-mounted brushes used for pasting. The sword at his waist reminds us he’s a samurai, if his regal bearing hasn’t already tipped us off.

There is no hint of the tengu in this portrait of Tengu Kōhei. Should there be? His daimei sounds like there should, but in fact his name is usually written not with the standard characters for the yōkai tengu 天狗, but with characters meaning “heaven’s fool” 天愚. But that hardly negates the sound association with yōkai tengu—in fact, it turns his name into precisely the kind of pun that early modern people relished. In other words, despite the fact that his name is written differently, we may expect that he was inviting us to see him as a tengu.

And that is precisely what some other senjafuda that refer to him do.

The first slip above features a partial reproduction of one of Tengu Kōhei’s own harifuda on the right (it gives the full version of his daimei, Kyūkoku Tengu Kōhei). On the top left it gives us a caricature meant to represent Kōhei himself. Two jokes are embedded in the caricature. First, the lines that constitute it are, in fact, the characters for “Kyūkoku” and “Kōhei,” radically deformed. Second, the face is drawn in the shape of a tengu mask, with the giveaway protruding nose. This mask forms the missing “tengu” element of the name, and also tells us that senjafuda practitioners clearly associated Tengu Kōhei with the yōkai.

The second slip associates a later practitioner with Tengu Kōhei. The characters running down the right edge say “Past—Tengu Kōhei,” while those running down the left edge say “Present—Ōma Heikō.” The large characters in the center say “Heikō,” the name of a present-day senjafuda aficionado (and of course phonetically “Heikō” is “Kōhei” in reverse). Above Heikō’s name is a similar character-based caricature of a tengu mask, labeled “the original paster.”

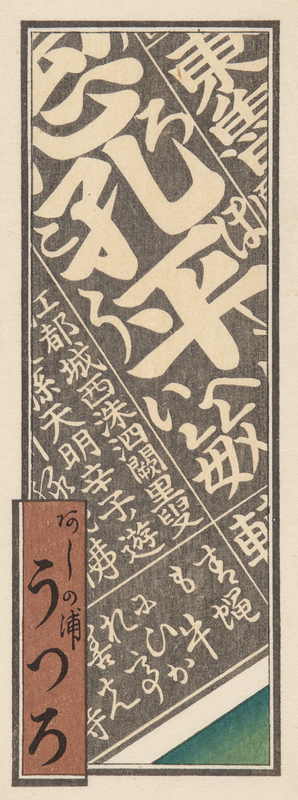

The third slip features a partial closeup of a well-known harifuda belonging to Tengu Kōhei himself. In large characters we see “Kyūkoku” and “Ten” with “gu” cut off by the orange daimei label. The daimei cleverly associates the sponsor with Tengu Kōhei, however, because the daimei reads “Tenman Ōnaka,” with the “ten” of the daimei picking up where the “ten” of Kōhei leaves off—a graphic illustration of how closely later practitioners identified with their famous predecessor.

The fourth slip shows a closeup of a different section of Tengu Kōhei’s harifuda. It almost, but doesn’t quite, link up with the one on the left.

Why would Tengu Kōhei choose to associate himself with a yōkai? Since, on the surface, he didn’t, we can’t know for sure. But for anyone aware of the tengu’s complicated relationship to Buddhism in medieval legend, there couldn’t be a more appropriate choice. Tengu are both enemies of Buddhism and protectors of it, monstrous parodies of monks and embodiments of priestly transcendence. Like tengu, senjafuda practitioners had a love/hate relationship with temples: practitioners saw (or pretended to see) pasting as a devotional act, but temples tended to see it as anything but. Senjafuda practitioners could see themselves as, like tengu, simultaneously heroic in their faith and outlaws in their expression of it.

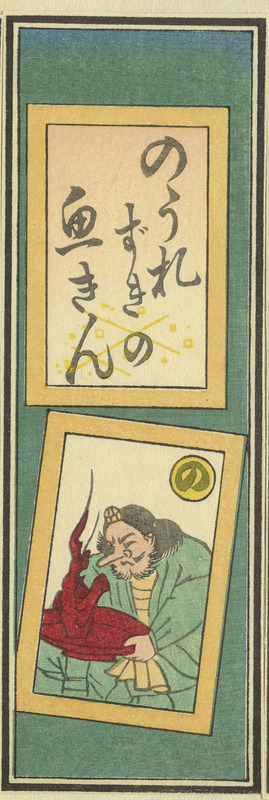

The first slip above is part of a series based on iroha karuta, a card-matching game linked to the Japanese syllabary. In its orthodox form, one set of cards would each have a poem on it beginning with a different syllable. Another set of cards would have that syllable accompanied by an illustration. The picture-cards would be scattered on the floor, and one person would read the poem while other players scrambled to find the matching card. In this case, instead of poems the upper card contains a phrase having to do with senjafuda or one of the members of the ren. This one says “Uokin, a nōsatsu lover.” The bottom card has the corresponding syllable “no” plus an illustration of a tengu examining a piece of wood (or coral?) mounted in an ikebana dish. This is an example of a tengu being used to represent a senjafuda participant.

The second slip provides another example of tengu as part of a participant’s self-representation. The linked circled design at the top (actually a stylized 中 or “naka”), plus the smaller slip-within-a-slip, identify this as part of a series for the Nakabashi ren. The larger slip-within-a-slip has thumbnail sketches of an arrow, a crow tengu, and a butterfly. This is a rebus for the name of the participant.

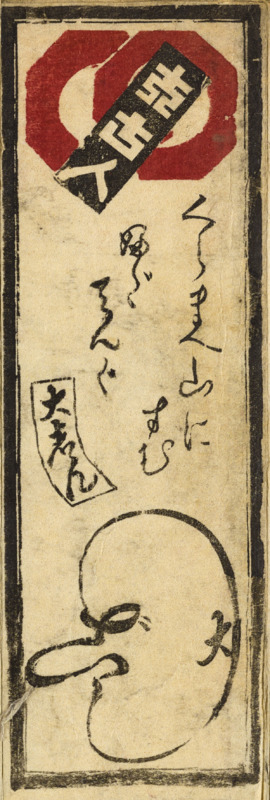

The third slip, for Daichin (or Ōchin) of the Hakkaku-ren, features the familiar tengu caricature with the phrase, “The fuda tengu who lives on Mount Kuramae.” This is a pun on Mount Kurama, the peak near Kyoto where Minamoto no Yoshitsune, according to legend, was trained in martial arts by the Great Tengu. Kuramae, meanwhile, is a neighborhood in Edo.

The fourth slip is a different copy of the Starr slip discussed on a previous page. The Starr collection understandably contains several copies of this slip.