Matchbox label series

Frederick Starr had good academic reasons for getting interested in senjafuda, but he also seems to have been a collector by nature. The UO’s Starr holdings include a wide variety of printed and handwritten ephemera in addition to senjafuda, ranging from printed shrine and temple charms to handwritten price tags from purchases of rice. Some of these items demonstrate the overlap between collectors’ and hobbyists’ circles in early 20th century Japan.

One particularly interesting overlap seen in the Starr collection is between senjafuda collecting and matchbox label collecting. In an era when smoking was much more common than it is today, and before handheld lighters became widely available, many people carried boxes of matches in their pockets. The labels attached to these boxes were opportunities for bold experiments in graphic design (not to mention advertising), and so it’s not hard to understand why they attracted collectors. As miniature examples of graphic design and high-quality printing they have many of the same charms as senjafuda.

In the case of Japan, matchbox labels had an added significance. Matches were an important export industry in late 19th and early 20th century Japan, so while many early designs display somewhat traditional-looking motifs, others make bold use of modern design concepts. As a result, matchbox label collecting seems to have been associated more with a rapidly modernizing, eagerly forward-looking Japan than with the nostalgia that characterizes senjafuda collecting.[1]

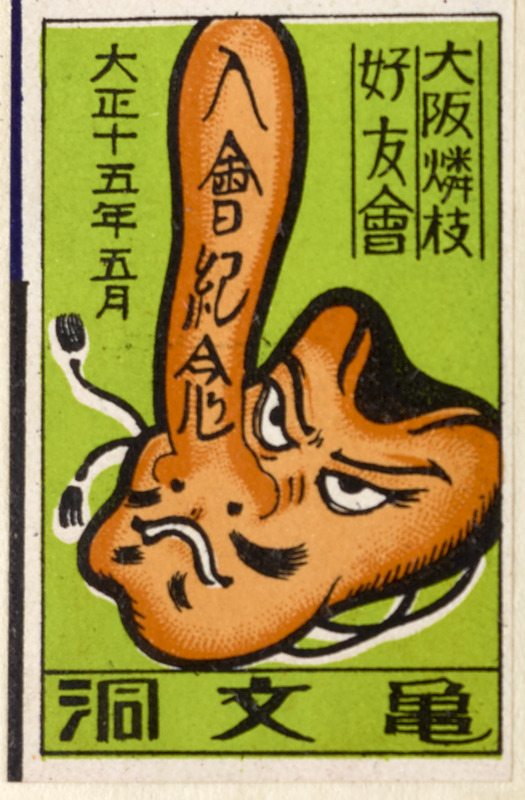

The Starr collection contains a few dozen matchbox labels. Many of them contain the names of collectors’ organizations and other indications that they were specially commissioned as commemorative items. One example is the tengu mask label below, which says, “Osaka Match Aficionados Association, May 1926.” On the tengu’s nose is written “commemorating entry into the association,” presumably referring to Kibundō, the pseudonym written at the bottom of the label.

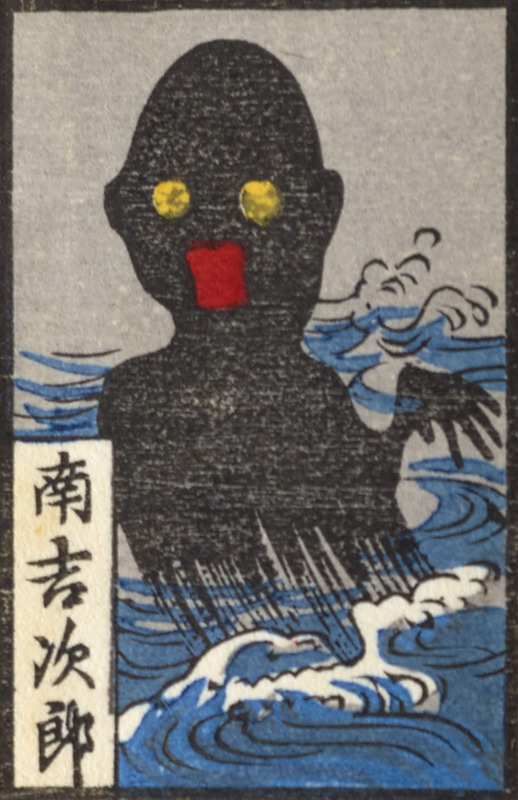

While most matchbox labels were made by modern printing processes, some were woodblock printed, and this appears to be the case with most in the Starr collection. Among them are the ten yōkai labels below. All contain the name Minami Kichijirō, a name that appears in many of the Starr labels, often with late-1920s dates. The presence of Minami’s name and no company or other information suggests that these, too, were privately commissioned.

The ghosts and monsters depicted on these labels are not identified, but they’re clearly influenced by Edo period depictions of yōkai such as the sugoroku board discussed elsewhere. Their format is reminiscent both of senjafuda and of another variety of woodblock-printed toy popular in the Edo period, iroha karuta. Karuta are discussed elsewhere on this site; here we’ll note that one variety of karuta, produced as late as the early 20th century, used yōkai as the visual motif. Karuta’s dimensions and proportions weren’t so different from those of matchbox labels, which may have played a part in the design of this series of labels.

Discussion of individual yōkai in the matchbook labels

From left to right:

A one-eyed boy holding a covered teacup. Visually quite similar to the “One-Eye of Liar’s Moor” on the sugoroku board, complete with lolling tongue. Since he holds a teacup instead of a tray of tofu we’d probably consider this a hitotsume kozō or one-eyed boy.

A woman with an elongated neck. Plainly a rokurokubi, and a much more orthodox depiction of one than the “Latheneck in the Old Chest” on the sugoroku board.

A woman dressed in white and a wisp of flame or red smoke. White robes, unkempt hair, and a body that trails off into nothingness where feet should be are all standard features of traditional depictions of yūrei or ghosts, and depictions of female ghosts were far more popular than those of male ghosts in late Edo and Meiji Japan. The flame, too, suggests a disembodied spirit (as in the “Jealous Grudge” on the sugoroku board).

A paper lantern with a human face appearing on it; a tear near the bottom of the lantern doubles as a mouth, and the flame inside is roaring forth like a tongue. This is a clear reference to the famous scene in Yotsuya kaidan where the ghost of Oiwa appears in a paper lantern that bursts into flames, a scene also depicted on the sugoroku board.

From left to right:

This looks like a closeup of a ghostly face, but the way the head dominates the frame suggests the artist is thinking of the ōkubi or “huge head,” an apparition depicted in Konjaku gazu zoku hyakki (Illustrations of a Hundred Demons Past and Present, Continued), Toriyama Sekien’s second bestiary. Sekien describes it as appearing on dark and rainy nights, and notes that “anything huge is scary.”

A hairy man with a fierce expression and hands held in a menacing pose. This yōkai is too generic to allow for sure identification, but it is somewhat reminiscent of depictions of the mikoshi nyūdō (including that on the sugoroku board); usually this yōkai is shown with neck extended, but not always.

The ghost of Kasane, almost as popular in 19th century theater as Oiwa; of particular note was the extended horror rakugo Shinkei Kasane-ga-fuchi (A True View of Kasane Pool) of 1859 by San’yūtei Enchō, in which a sickle is used as a murder weapon.

A three-eyed monster. Like the “Great Three-Eyed Priest of Asahina Pass,” this is an example of a mitsume. Interestingly, this specimen is probably also being presented as a priest: the item in its hand is probably the end of a conch shell (actually a "Triton’s trumpet"), used as a ritual musical instrument in some Buddhist sects.

From left to right:

Another female ghost, too generic to be identified with any particular story. The wooden posts in the background (also visible in the label depicting Oiwa as a lantern) are stupas marking graves.

An umibōzu very similar in appearance to the “Sea-Monk of the Genkai Sea” on the sugoroku board.

References

[1] For more about Japanese matchbox labels in the early 20th century, see Maggie Kinser Hohle, Matchibako: Japanese Matchbox Art of the 20s and 30s (Mark Batty Publisher, 2004).