Oni

Oni are by far the most common yōkai in senjafuda (as seen in the UO collections), if only because what we’re calling oni comprise such a broad category. These creatures are immediately identifiable (although there are a few visually distinctive varieties), but surprisingly hard to define.

This hard-to-define-ness comes out in the varying translations used for the word oni 鬼. Sometimes it’s translated “demon” and sometimes “ogre.” But for most English speakers, “demon” and “ogre” have very different connotations. We tend to associate demons with hell, the afterlife, sin and its punishment, and evil. By contrast we tend to imagine ogres as earthly creatures: maybe big and lumbering and hostile, but not necessarily evil in a metaphysical way.

The concept of oni encompasses both of these figures. Some oni are this-worldly monsters: big, toothy, and scary, but not denizens of hell. Other oni are not just residents of hell, they’re its staff: jailers and torturers who administer the most macabre of punishments to sinners. But the concept of oni is even broader than that. The word oni (in the character’s alternate reading of ki) is embedded in the traditional name of the night parade of a hundred demons, discussed extensively elsewhere on this site. But any artistic representation of that parade includes many, many monsters that don’t fit either of the above descriptions of oni. In fact, the term oni is traditionally used as a catch-all term for all kinds of monsters; in a sense, it’s almost a synonym for yōkai itself.

The concept gets even more elastic when we take into account the fact that some characters for “spirit” incorporate the character for oni, or even use it outright. In other words, there’s conceptual overlap between oni and ghosts, too. Finally, some gods are represented in the form of demons, which destabilizes any neat opposition we may want to find between good and evil, heaven and hell, high and low, in oni lore.[1]

This page will explore the variety of ways oni manifest themselves in early modern yōkai lore, as seen in senjafuda.

Identifying oni

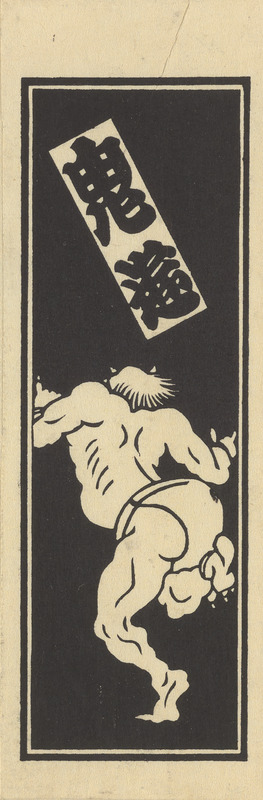

As noted above, oni are generally easy to identify. They have horns and sharp teeth. They’re generally either red or blue/green (ao 青, a color concept that can encompass both blue and green). They’re large and muscular and generally fierce-looking. They often carry weapons; an iron club is a favorite. They’re usually shown dressed in loincloths or skirts made from the skins of tigers or other exotic animals.

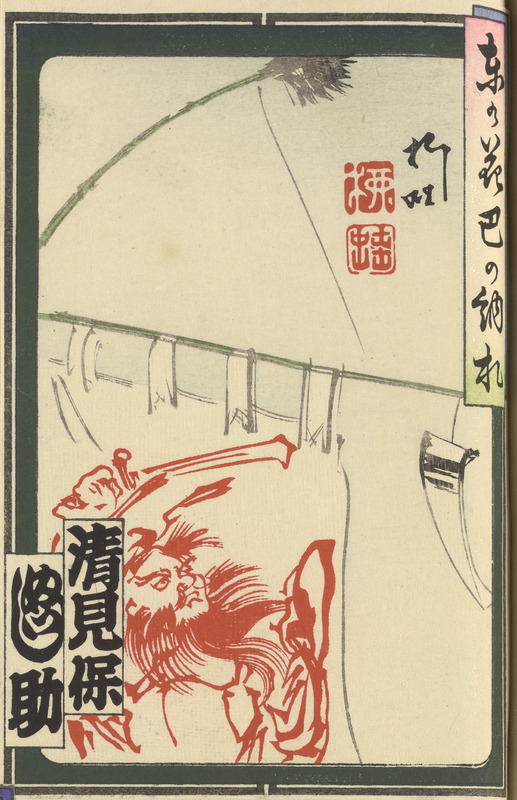

The slip in the center above is in many ways typical. It shows a red-fleshed oni with horns, sharp teeth, sharp claws, and brawny build. It also has wild curly hair. It’s wearing the skin of a lion or similar creature around its waist; it also has shinguards that look to be made of the same material. Its bracelets and flowing scarf-like wrap are also items often seen on oni. The slip on the left shows much the same type of oni: this one is green-skinned and has flamelike eyebrows and facial hair (perhaps they’re actual flames).

The slip on the right shows one significant variation or subcategory in oni iconography: the hannya. The word hannya ultimately derives from the Japanese name of the Buddhist Prajnaparamita sutras. It comes into oni lore as the name of a type of mask used in noh plays. One theory is that the medieval craftsman who designed the mask went by the name Hannya, and so the mask was named after him. In any case, the mask is often white or light-colored and has long horns, devilish eyes, and a wide, toothy smile. In noh plays it’s used to portray women who have been transformed (usually by jealousy or rage) into monsters or demons; such characters often carry a red and white striped staff known as an uchizue, meant to represent an oni’s weapon. So well known did this mask become that often female demons are drawn with faces identical to it, and many modern people use the term hannya to refer to female demons in general.

Ogre-like oni

The three images below show oni in aspects close to what is conjured up by the English word “ogre.”

The first is a four-chō senjafuda depicting a wooden votive plaque, itself depicting an oni known as Ibaraki Dōji (wooden votive plaques in general are discussed on the “Origins and offerings” page). In the most familiar forms of his tale, Ibaraki Dōji is an oni retainer of an even more powerful oni called Shuten Dōji, who lives on Mount Ōe (Mount Ibuki, in some versions) and kidnaps women to devour them. (Three versions of the main Shuten Dōji story may be viewed on the Hyogo Prefectural History Museum's website.) Shuten Dōji is defeated by a band of warriors led by Minamoto no Raikō; one of Raikō’s retainers, Watanabe no Tsuna, cuts off Ibaraki Dōji’s arm and takes it home as a trophy. To get his arm back, Ibaraki Dōji disguises himself as Tsuna’s aunt and sneaks into his house. In the image, Ibaraki’s arm is oni-red, while the face, while lacking horns, is reminiscent of a hannya mask—appropriate, since he’s in the guise of a woman.

The next two images are prints by Tsukioka Kōgyo depicting the noh play Rashōmon (Kōgyo’s noh prints are also discussed on the tengu page). This play is based on old legends that said an oni lived in the top of the huge, ruined Rashōmon gate at the southern entrance to Kyoto (a medieval story about this demon was adapted into the story “Rashōmon” by modern writer Akutagawa Ryūnosuke; his story provided the framing device for Kurosawa Akira’s classic film of the same name). In the play, Minamoto no Raikō and his men are drinking when they hear rumors of the oni in the gate, so Raikō sends his retainer Tsuna to check on it. Tsuna encounters the demon and defeats it by cutting off its arm. The parallels between this story and that of Ibaraki Dōji are curiously close; Noriko Reider explores them in Chapter 2 of Japanese Demon Lore.[1]

In the first print, the viewer is placed behind the actor playing Tsuna, so that we, like Tsuna, are facing the oni head on. In the play, the oni attacks Tsuna from behind, tearing off his helmet; in the print, the oni holds the helmet to its chest—it’s covered with black hair and has two metal ornaments protruding from the top. In the second print, the helmet is shown in an inset. The contrast in composition between these two prints is striking, one showing the oni towering over the warrior, the other perhaps suggesting a more even match.

Demon-like oni

The senjafuda series above is an example of oni appearing in a capacity that fits the English term demon. The series, also discussed on the page “Collectors and oni,” depicts in senjafuda form a hell scroll, a popular medieval way to depict the horrors of hell in an effort to convince mortals not to sin. Medieval and early modern Japan had an amazingly detailed iconography of hell (discussed further by Caroline Hirasawa),[2] and this “scroll” shows many of the best-loved (or most-feared) features of it. After a dedicatory inscription we see a milepost for the River of Three Ways (Sanzu no kawa 三途の川), the border of hell, and then we encounter datsueba 奪衣婆, the “robe-stripping crone,” a figure who relieves the newly dead of their clothes. The next panel is missing from the Starr Collection version of this series, but from the desk and mirror on the next panel we know it features Enma, King of Hell, who sits at his bureaucrat’s desk and judges the dead before sending them off to the appropriate punishment. A pale dead man kneels before the desk pleading, while another behind him is being dragged off by a blue-skinned oni.

The next several panels show oni in their element, tormenting sinners. We see red, blue, and green skinned oni wielding clubs and swords. We see them tossing sinners into a boiling cauldron (which in some tellings contains human urine and feces), pulling them around in a flaming cart, beating them, dragging them by the hair, consigning them to a pool of blood, tearing them limb from limb. We also see the dead partially transformed into beasts. It’s a truly terrifying litany of tortures, and to be fair, this early 20th century rendition is tame compared to many medieval versions. But at the end there’s hope, as a bodhisattva appears in hell to deliver sinners into Buddha’s paradise. It’s a tour de force of senjafuda design, as well as a vivid example of the demon torturer aspect of oni.

Above are two more images of oni in hell. The first (also discussed on the “Collectors and oni” page) focuses on King Enma at his desk. Next to the desk stands Seeing Eye and Sniffing Nose, which help Enma discern people’s misdeeds, and a giant mirror that shows sinners what they’re to be punished for. Datsueba can be seen in the background, along with a pool of blood, a boiling cauldron, and other standard features of hell scenes. Of note are the two great bluish oni on the left. One is staring at the mirror, while the other is seems to be looking out of the picture at us. The second image (also discussed on the “Yōkai, collectively” page) is an ukiyo-e diptych that features a comic reversal of the standard hell scene. Here a band of legendary heroes has come to hell and taken over, giving Enma and various oni a taste of their own medicine.

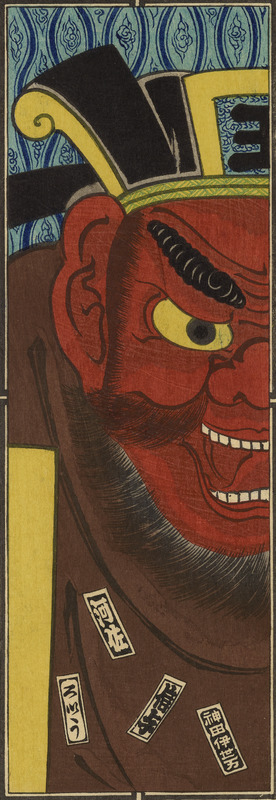

King Enma

King Enma is not himself an oni. An Indian deity absorbed into Buddhism, he was originally conceived of as a heavenly being before assuming his now familiar role as king of hell. Similarly, as Buddhism moved across East Asia the conception of what a king of hell would look like and do merged with Chinese beliefs about post-death judgments until Enma came to be called a king but sit as a judge. In Japan, he is invariably depicted wearing Chinese style clothing and surrounded by Chinese style furnishings and trappings of officialdom. (See Hirasawa [2] for more details about Enma.) He is also often depicted as red-faced, at least in senjafuda, suggesting a visual association with the oni that usually surround him.

Depictions of Enma are almost as popular in senjafuda as depictions of oni proper; several examples are seen above. Many of these are also discussed on the “Collectors and oni” page.

The first slip depicts Enma seated on his throne, staring off into the distance. The incense burner on the table in front of him tips the viewer off that this isn’t a picture of the “real” Enma, but rather an icon of him. Such icons are common in Buddhist temples in Japan, and the series title of this slip (“Annual Observances in Edo”) suggests that this is the icon found in the no-longer-extant Enma Hall in Asakusa. The second slip is doing the same thing, commemorating a “Famous Spot in Naniwa,” i.e., Osaka, the Enma Hall at Gappōgatsuji. The rest of the slips depict Enma (or Enma statues) interacting with senjafuda culture in various ways: holding up a votive slip in lieu of his standard flat wooden scepter, or maintaining his famous scowl in spite of slips being festooned on his shoulders, knees, or even nose.

Thunder gods

The four images below show not oni per se, but thunder gods, or raijin 雷神. But thunder gods, along with the wind gods or fūjin 風神 with which they’re sometimes paired (as in these famous 17th century screen paintings by Tawaraya Sōtatsu), are always depicted in ways that are hardly if at all distinguishable from oni. This may seem strange at first, given the strong association of oni with hell that we’ve just been exploring, but we should note that even in their capacity as hell’s guards, oni aren’t evil in the way Western culture envisions demons to be. Oni aren’t tempters, trying to entice people to hell; rather, they’re simply carrying out the necessary task of punishing sinners. If anything, they can be seen as serving Buddhist truth, rather than opposing it. This means that we shouldn’t perceive any contradiction between the same iconography being applied to oni and gods. Thunder is, of course, a fundamentally frightening phenomenon, so it’s doubly appropriate that when it takes a visible form it be monstrous.

In addition to the standard attributes of red skin, horns, and tiger-skin wrap, thunder gods are usually pictured with drums of some sort, often arranged in a circle around them. The rather friendly-looking thunder god in the first slip above is fairly typical (although his blue jacket is unusual). The second image above substitutes a large hand-drum for the ring of drums; this is a handcarved sculpture similar in feeling to, but larger than, a netsuke. The bodily detail given to the thunder god and his child is marvelous, if a bit creepy.

The third and fourth images are senjafuda playfully imagining what thunder gods can do from their vantage in the clouds. The first shows one fishing for daimei fuda; it may remind a modern viewer of certain carnival games. The second one shows a thunder god leering at the derriere of someone crawling into a mosquito net.

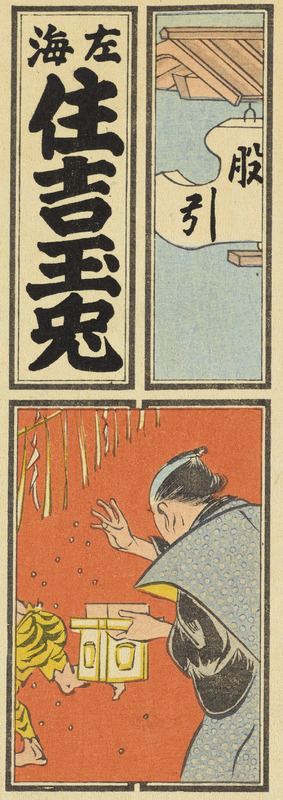

Repelling oni

If the conception of oni is broad enough and flexible enough to encompass gods, it’s still fair to say that on a basic level oni are perceived as being threatening and monstrous. It’s in that capacity that oni figure in a centuries-old custom that, judging by senjafuda, people had a lot of affection for in the early 20th century (many still do today, for that matter). Setsubun 節分, a holiday observing the beginning of spring (formerly coinciding with the lunar New Year), was observed by tossing a handful of toasted soybeans while saying “oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi”—“out with demons, in with good fortune.” Oni in the saying can be taken metaphorically, to mean bad fortune or bad influences, but was often represented literally—in some places, the beans were thrown at a person wearing an oni mask, to chase him away.

The first slip above, a four-chō senjafuda labeled “Setsubun,” can be taken as a “straight” representation of this tradition, although the formal trousers of the man throwing the beans and the boy holding the lamp mark this as a high-ranking samurai household, and thus nostalgic from the early 20th century vantage of this slip. The second slip is a little more imaginative, as we can see the hindquarters of an oni fleeing from the man throwing beans. The third slip refers to the practice by pairing an oni mask with a mask of Ofuku (also discussed on the “Tengu” page).

The next two images are gorgeous ukiyo-e triptychs on the same theme. The first is by Kawanabe Kyōsai, the artist who designed the hyakki yagyō accordion book discussed elsewhere on this site. Here the person throwing the beans is Kintarō, a legendary boy hero; he’s surrounded by grown women in what appears to be the women’s quarters of a wealthy household. The oni he’s chasing away are depicted as comically small figures reminiscent of yanari 家鳴, “house creaks,” tiny oni famously illustrated by Toriyama Sekien; like Sekien's yanari, these oni are tumbling around on the veranda of a house. The mismatch between Kintarō and the oni, and the busy colors and patterns of this print, lend it a festive air, to say the least.

A creepier take on the same idea is found in the next image, a triptych by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (discussed in relation to cats elsewhere on this site). Here the boy hero is Peach Boy (Momotarō 桃太郎), who famously conquered an island of oni with his sidekicks Pheasant, Monkey, and Dog. Daikoku and Ebisu, two of the Seven Gods of Fortune, look on as Peach Boy (in kabuki makeup) tosses beans at two fleeing oni. In contrast to the cheerful spirit of the previous print, this one places the scene in the dead of night and surrounds the figures with darkness. Behind the red and blue demon are a large cluster of demons rendered in gray—suggesting they’re invisible to the participants in the scene. The barely glimpsed chaos gives this print something of the air of a hyakki yagyō scene.

The final image is a senjafuda announcing a women’s senjafuda exchange meeting to take place in the first hours of the New Year. Oni can be seen fleeing a girl holding a votive slip, rather than a man throwing beans. Other slips imagining an intersection of setsubun customs and senjafuda are discussed on the “Collectors and oni” page.

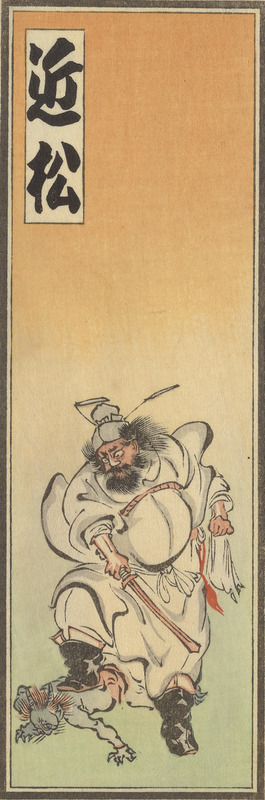

Shōki

In the slips depicting setsubun traditions, oni are usually present but deemphasized, reduced in size or dignity or both, as in the Kyōsai print. Their function in setsubun traditions, after all, is to be chased away—they represent the baleful influences and ill fortune we wish to be free of. Oni play a similar role in the images above, which all depict a figure known as Shōki 鍾馗 (Ch. Zhong Kui), a demon queller of Chinese legend. Like King Enma, then, Shōki himself is no demon, but is always depicted in the company of demons, and displays an oni-like ferocity. Shōki iconography was popular in early modern Japan (and therefore in senjafuda) both for his obviously charismatic ferocity and because images of Shōki were used as charms to ward off illness, particularly smallpox.

The first image above is an ukiyo-e by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (discussed in connection with cats elsewhere) that shows the standard Shōki iconography: a massive warrior in Chinese garb with a great flowing beard and a big sword, with an oni cowering in fear. The next several images all adapt this basic iconography to the senjafuda format, usually with a clever twist.

The next three are discussed on the “World of senjafuda” page. They are a typical one-chō and two two-chō slips utilizing Shōki as a motif. In the two-chō slips, the oni are fleeing in a flurry of daimeifuda, suggesting either that the power of the slips is helping drive them away or that the oni were pasting or collecting slips (either idea would be in line with senjafuda practitioners’ self-presentation).

The first slip above has Shōki sticking his arm through a window-like roundel; his gaze and the motion of his sword suggest less demon-quelling than paddling a naughty child. The parent-child motif implicit here is made explicit in the next two slips. The first shows Kintarō besting Shōki, who is tumbling backward in alarm. The second shows Shōki eyeing Kintarō warily, as if trying to decide if he needs quelling.

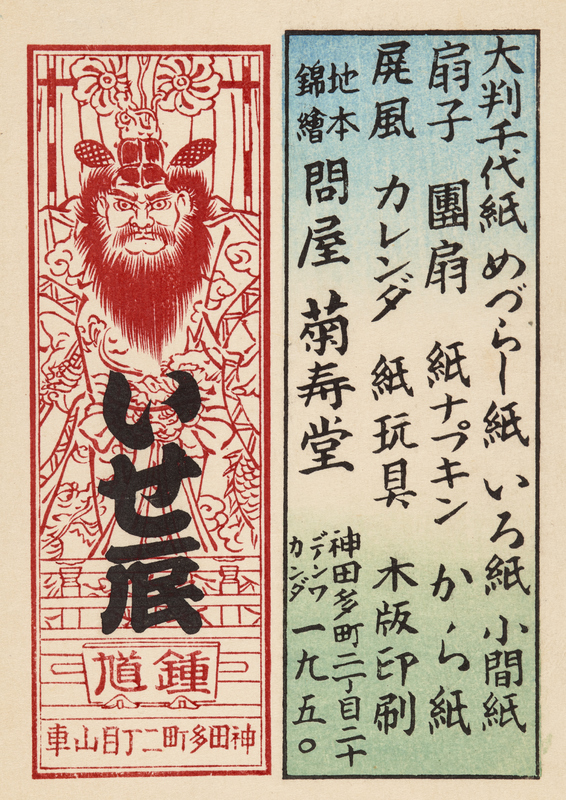

The rest of the slips above are, like many of the Enma slips further up the page, not depictions of Shōki himself, but depictions-of-depictions of Shōki. The first shows the Shōki-and-oni figure that sat atop one of the Kanda Festival floats; this is from the same series as the tengu float-topper discussed elsewhere.

The next two slips both show banners depicting Shōki, which were often displayed on the fifth day of the fifth month, a holiday known as Tango no Sekku. This day was marked by displaying dolls, banners, streamers, and other decorations bearing imagery thought to be auspicious for the raising of strong, healthy boys (Momotarō and Kintarō were also popular motifs). Note that in both of these slips, Shōki is depicted in red. Banners with auspicious masculine imagery rendered in red were thought to be charms against smallpox; prints in red ink were made for the same purpose, and were known as hōsōe 疱瘡絵 or “smallpox pictures.”

The last image of Shōki above (further discussed on the “Nostalgia” page) may be meant to suggest a hōsōe. It’s another depiction of the Kanda Festival float showing Shōki.

Ōtsue

The images above relate to another type of religious folk art featuring oni: Ōtsue or “Ōtsu pictures.” The name comes from the fact that they were specialties of the town of Ōtsu on the southern edge of Lake Biwa; this was a town on the Tōkaidō, the main road connecting Edo and Kyoto, so any traveler between the country’s two biggest population centers would pass through it. Ōtsue were simple pictures, often with a religious theme, sold to tourists.

As popular souvenirs throughout the Edo period, their distinctively primitive imagery became widely recognizable, as did their repertoire of stock images. They were also seen as important examples of early printed art—they were often made with simple printed outlines to which color was applied by hand. For all these reasons, they were bound to catch the antiquarian eye of the senjafuda collector. This included Frederick Starr himself, as several examples of Ōtsue made their way into his collection, including the first three images below.

The first, pasted into one of his senjafuda albums, seems older than the other two. It also shows a key motif echoed in senjafuda: an oni dressed as an itinerant monk. Key to the iconography of this figure is the small gong hanging around his neck, the T-shaped stick with which it is beaten, and the pad of paper hanging from his sash in which to record the names of almsgivers. The next two are more recent than the first; they’re stamped “Ōtsue” and have the artist’s name: Shōzan, a modern Ōtsue revivalist. The first is another version of the oni-priest motif, while the second shows a thunder god trying to snag a drum that has fallen from his cloud.

The next two images are senjafuda adaptations of the Ōtsue oni-priest; especially in the case of the second one, it’s probably fairer to say that they’re senjafuda playfully masquerading as Ōtsue. Each has a pad of paper on which is written, not “almsgivers,” but the daimei of the sponsor of the slip. The first one says “Kanda” in the upper portion of the slip, identifying the neighborhood in which the sponsor lives; the second one has a Sanskrit character that represents the bodhisattva Miroku.

The last two images repurpose the Ōtsue oni-priest for humorous purposes. In the first image, he’s carrying a maiden across a river on his back; the maiden is holding a sprig of wisteria. In fact, the wisteria maiden was another popular Ōtsue theme, so this is a humorous pairing of two Ōtsue in “real life.” The image of a man carrying a woman across a river on his back was a common one in depictions of the Tōkaidō, because most of its river crossings had no bridges; wealthy travelers could be carried across on a platform, while less wealthy ones rode on a porter’s shoulders or simply waded (like the down-on-his-luck Daikoku in the background). The oni-priest is rendered in humorously naturalistic detail, with his gong and mallet tucked into his robes and a decidedly nonplussed expression on his face.

In the second image, an oni-priest kneels on a red carpet in the manner of a rakugo storyteller greeting his audience; the mallet for his gong is placed in front of him much as a storyteller would place his folding fan. The art here is closer to the coarse brushwork of the typical Ōtsue, but the facial expression is lively and personable, suggesting a storyteller just about to crack his first joke.

A day in the life of oni

The slips below are a series prepared for an exchange meeting held on February 3, 1925, according to the first slip. The theme isn’t specified, and it’s not immediately apparent from the first slip itself, which shows a Buddhist figure scooping up dead souls with a fishing net.

Iconographically, this may be Amida, but the woven hat on his head (doubling as a halo) also puts one in mind of the bodhisattva Jizō; both figures are seen in the hell scroll series discussed above. In any case, the joke here is that this figure can simultaneously be seen as a fisherman, hat protecting him from the sun, scooping fish from a lotus pond, and as a haloed deity saving sinners from hell. Since the rest of the series depicts oni at leisure, the implication may be that since Amida has saved everybody from hell, the oni are now free to enjoy a little down time.

What follows is one of the cutest series in the whole collection, as we get a glimpse of adorable oni and King Enma himself going about a variety of hobbies and chores.

In order from left to right we see:

King Enma getting a much-needed shoulder rub while an oni sets up two of his demon-headed implements.

Enma conducting a tea ceremony.

An oni tying a bunch of torture implements in a bundle, perhaps to put them away for safekeeping, while gabbing with another oni.

An oni fishing from a riverbank while two more relax on a boat; one is napping while the other is smoking a pipe (note the horns sticking through his hat).

From left to right:

Two oni engaged in a game of go while a third looks on.

Enma seated at his desk catching up on some paperwork, with one of his lieutenants seated next to him. An oni has brought in a cup of tea, so Enma leans back and stretches. Note that Enma isn’t wearing his hat—this is a private moment.

Two oni matrons picking herbs and wildflowers while talking with a child.

A group of oni children playing blind-man’s bluff (the game of tag is called “playing oni” in Japanese, with the child who’s “it” called the oni, making this a double joke). Note the girl oni hiding behind the door.

From left to right:

An oni lying in the grass smoking a pipe while the cauldron he used to tend sits empty. A cat has had kittens in the space where the fire used to be, and the oni’s daughter is bringing him one to play with.

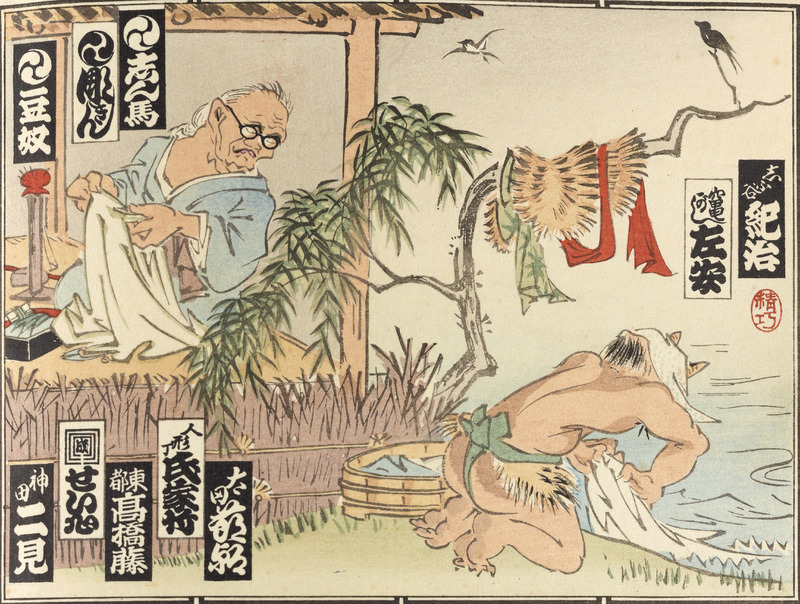

One oni mends clothes while her husband does the washing.

An oni uses Enma’s soul-revealing mirror to do some personal grooming. If the tweezers in his hand aren’t sufficient, he has a set of tongs next to him that were once used to torture sinners.

An oni burns moxa on her husband’s back to relieve his aches and pains (a mild torture compared to what he’s used to dishing out).

From left to right:

Enma relaxing on his throne, reading a newspaper.

An oni enjoying a picnic with his son.

An oni boy sitting on an ox, playing a flute (this was a popular motif in Chinese painting, only with a boy instead of an oni).

An oni putting out the fire on his flaming cart, since he doesn’t need it anymore.

References

[1] The most comprehensive treatment of oni in English is Noriko T. Reider, Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present (Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2010).

[2] Caroline Hirasawa, “The Inflatable, Collapsible Kingdom of Retribution: A Primer on Japanese Hell Imagery and Imagination,” Monumenta Nipponica 63.1 (Spring, 2008), pp. 1-50.