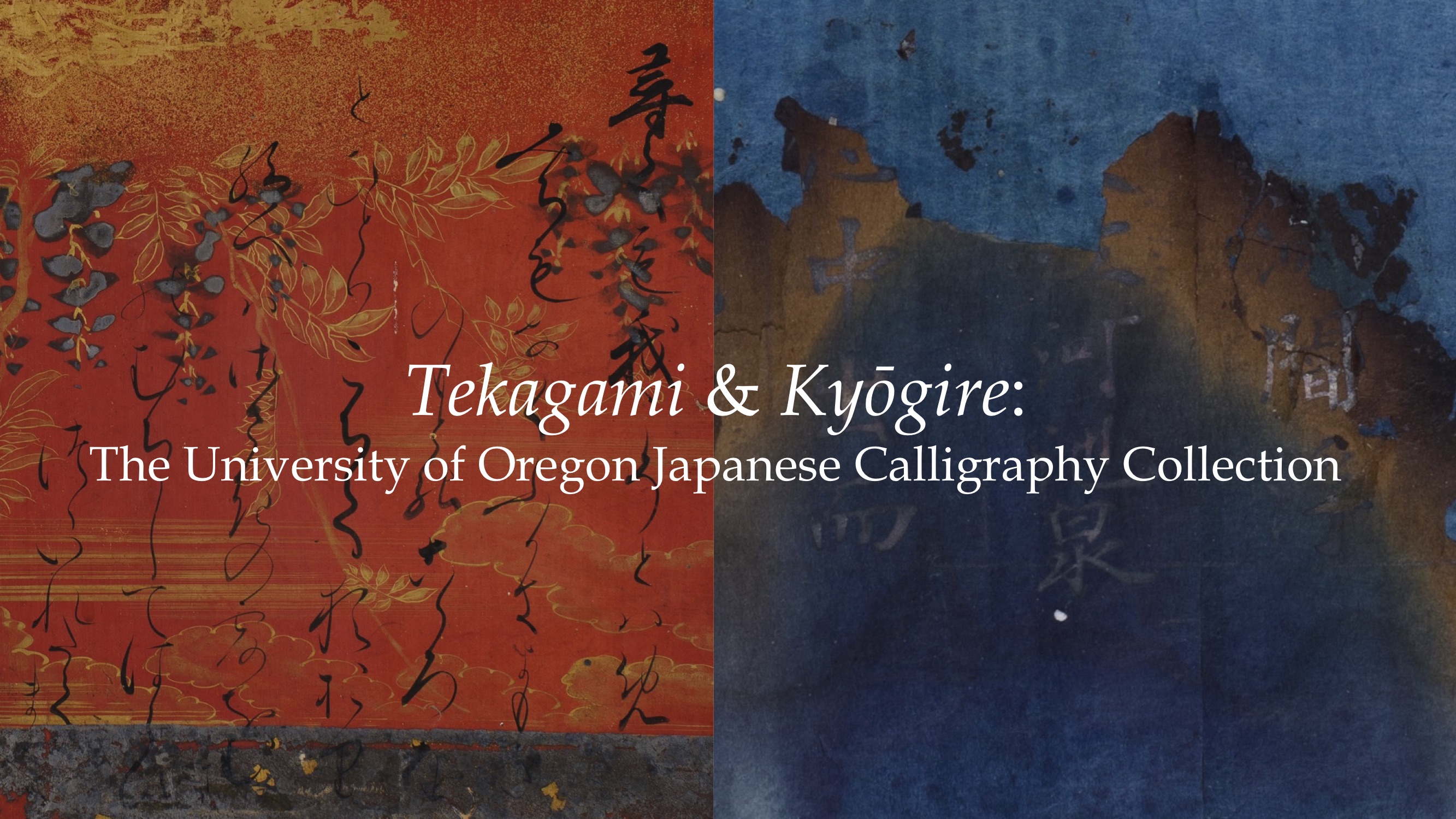

Welcome to Tekagami and Kyōgire, a digital exhibition featuring the collection of fragmented calligraphy at the University of Oregon.

In East Asia, calligraphy was (and to certain extent still is) considered the most noble form of art that could reveal the very essence of a person. Unlike pencils and pens we use for writing today, the traditional East Asian writing utensil was a brush with a rather flimsy tip made of varying materials, most typically horsehair. The softness of the tip gave a brush great fluidity and freedom of expression, while demanding of its user incredible self-discipline and control of one’s body. For this reason, all writing in East Asia was not just communication, but a performance. An accomplished hand, therefore, was revered, eagerly sought after, and studied.

In China, an emperor of the Tang Dynasty called Taizong (r. 626-649) famously ordered an authentic work by the greatest “calligraphy sage,” Wang Xizhi (303-361), to be buried with him upon his death. The fervor for not just studying but collecting calligraphy was shared in Japan throughout its history of writing, first among the intellectual elites, like the aristocrats, Buddhist clerics, and literati, but eventually among every stratum of society as the rate of literacy rose beginning in the seventeenth century.

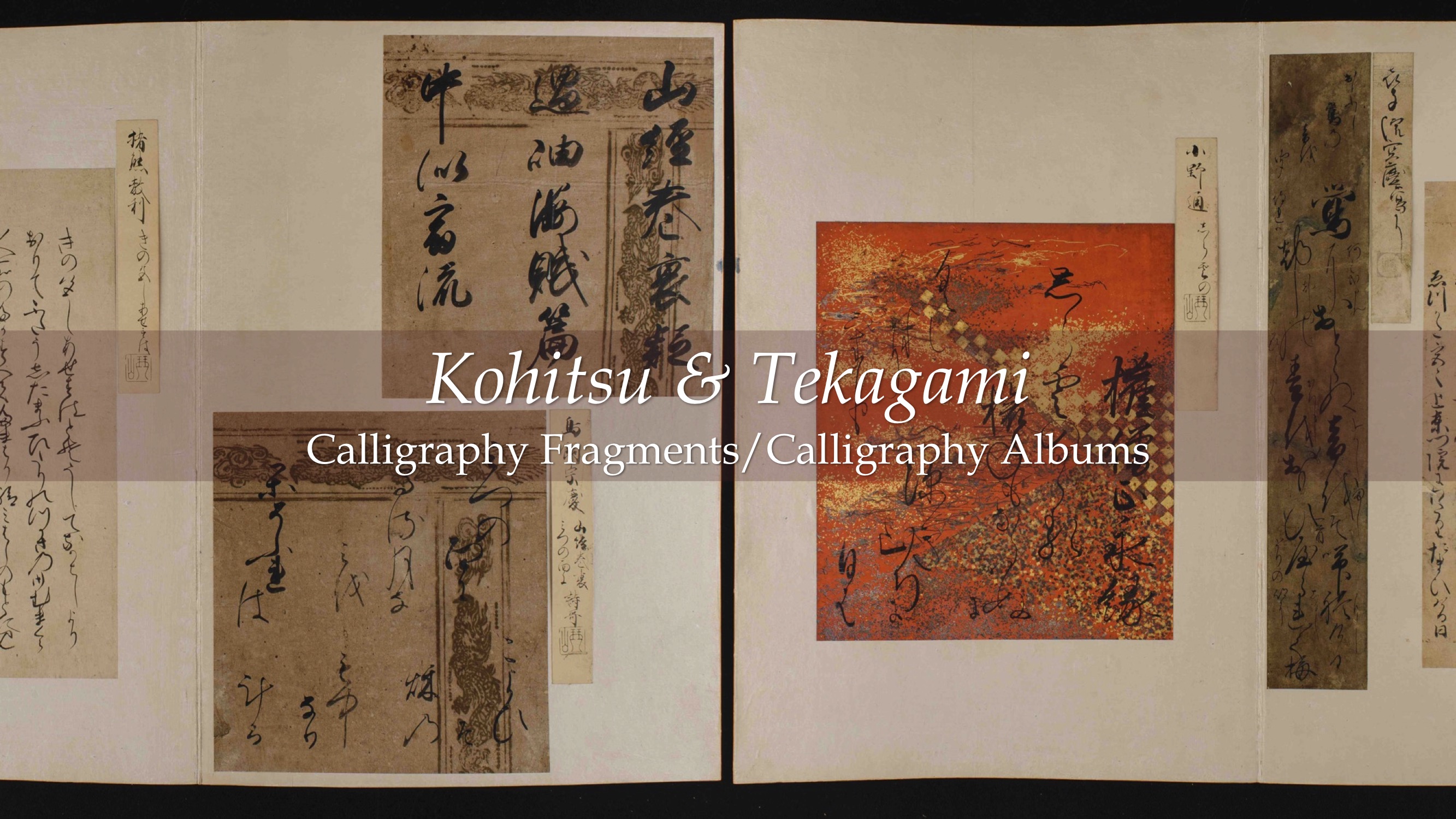

This exhibition introduces two gems of UO’s collection of Japanese calligraphy: the album of calligraphy known as tekagami in the collection of the Knight Library Special Collections and UO Archives (SCUA), containing a total of 319 examples; and thirty-six individually mounted calligraphy fragments in the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (JSMA). Together, the collection showcases some of the most beautiful and representative examples of Japanese calligraphy with a dizzying array of paper decoration, ranging in dates from the eighth to seventeenth centuries, and content from copied sacred scriptures, poetry slips, and narrative stories to personal letters.

The metadata for the calligraphy fragments included in this website are the fruits of research conducted by Akiko Walley during the Mellon fellowship period in 2019-20, but they are still a work-in-progress. Although incomplete, they are shared in hopes that they may spark interest in this material and contribute to the future discovery of other similar works in collections outside of Japan. The information will continue to be updated in the future.