Appreciating Tekagami

Just as the Oregon Tekagami, most tekagami albums follow the general organizational principle based on the societal role and status of the attributed calligraphers yet deviate from it rather freely at places. This is partly due to the reality of tekagami collecting that each kohitsugire included was a precious artwork and marketable commodity. Naturally, not everyone enthralled by kohitsugire collecting in the Edo period could have afforded examples by the most coveted calligraphers.

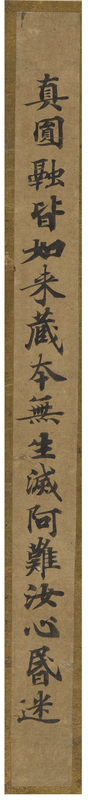

In the case of the Oregon Tekagami, some of the anchoring calligraphers—such as Emperor Shōmu on Page 1, with whom every “proper” tekagami album was expected to begin, or Monk Kūkai 空海 (also known as Kōbō Daishi; 774-835) on Page 2, who was revered as one of the three calligraphy sages (sanpitsu 三筆) of the early Heian period—are represented only by a single line of calligraphy sample.1 This probably suggests that whoever compiled this album was not the wealthiest of collectors.

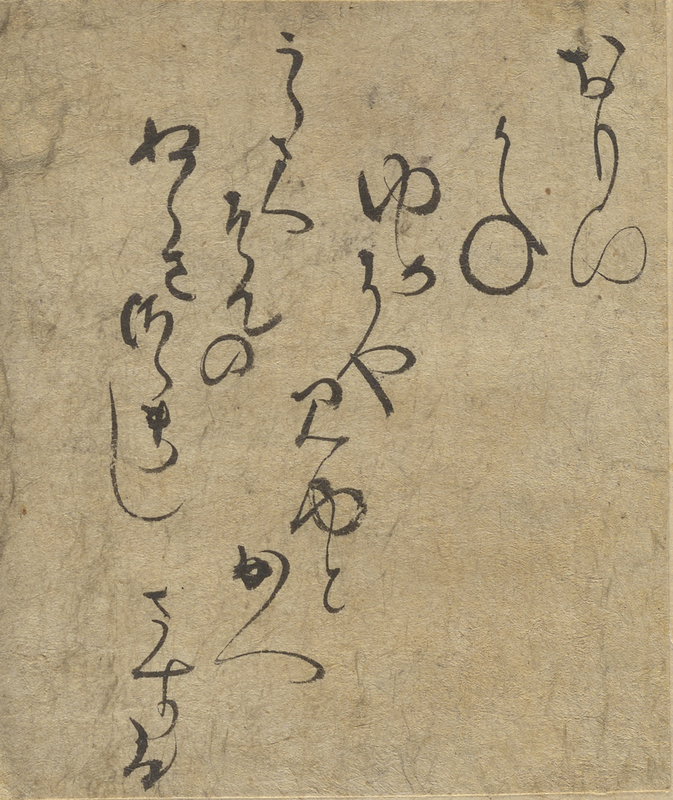

On the other hand, as the “Scholars’ Picks” column by Professor Sasaki Takahiro explains, some of the smallest fragments in the Oregon Tekagami, such as Fragments 143, 172, 264, 276, and 279 are the absolute cream of the crop of Japanese calligraphy, conveying to us the priorities of our anonymous collector. It appears that whoever assembled the Oregon Tekagami opted for quality over flashy notoriety.

In a sense, the common practice of repasting also attested to the reality that a highly coveted fragment was a valuable asset and an independent work of art that could be appreciated in alternate formats (such as a hanging scroll or folding screen).2 For this reason, a tekagami album should be considered at once a mode of exhibition and a kind of vault for safekeeping the valuable pieces of art.

In modern times, an antique dealer who came into possession of a tekagami album often removed the fragments and sold each of them individually. Popularity of kohitsugire collecting continued even after the fall of the Tokugawa regime in 1868, and it still continues even today. It was (and is) far more profitable for dealers and affordable for their prospective customers to sell the fragments individually. A tekagami is a collection of fragmented parts, and the customs surrounding this particular collecting practice ensured fluidity of these fragments.

To put it differently, the natural state of kohitsugire was as fragments, so any assemblage was bound to be temporary and transitory. From today’s perspective, it is thus very fortuitous that Mrs. Warner had the foresight (not to mention the means) to purchase the Oregon Tekagami in its entirety, preserving one complete vision of an ensemble.

Below you will find a close-up view of the entire Oregon Tekagami, one two-page spread at a time. By clicking on "More Information," you will be able to access the links to the metadata of the calligraphy fragments pasted on the page. As one looks at a tekagami, it might be fruitful to consider each of these two-page spreads as a single spatial unit. The fact the not everyone could afford all the pieces required to put together a textbook tekagami that fully followed the standard organizational principle by social hierarchy can be interpreted more positively: The creativity with which collectors departed from the norm was what showcased their aesthetic taste and erudition.

Calligraphy was revered as the highest form of artistic expression in East Asia because it encapsulated the essence of the calligrapher’s inner qualities. If so, the challenge and joy of laying out a tekagami must have been to decide which calligraphers might be most intriguing to be placed side by side on the same spatial unit of an album (or who should never be allowed in the same “room”), which contents would create a coherent unit, and which fragments would look the most aesthetically pleasing together.

For further discussion, please see:

1. Compare for instance with the sutra fragment with five lines of bold characters attributed to Emperor Shōmu that opens the tekagami in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. ↩

2. Although no example of such a robe has yet been found, an Edo-period work of literature that often gets cited to illustrate the kohitsugire craze in the seventeenth century mentions a man who made a robe out of calligraphy fragments. A character in Ihara Saikaku’s 井原西鶴 (1642-1693) fiction called Kōshoku ichidai otoko 好色一代男 (“The Life of an Amorous Man”) appears in a luxurious paper jacket stringing together kohitsugire from a “tekagami authenticated by Kohitsu Ryōsa, a poem fragment by Fujiwara no Teika, three poems by Minamoto no Yorimasa, a long poem by Monk Sosei.” ↩