One-Character One-Buddha Sutra

Featured Fragment 1: X2010:1.8

What does it mean to fragment a sutra? An excellent example with which to consider this question is this fragment from a genre of copied sutra called, “One-character One-Buddha sutra” (ichiji ichibutsu kyō 一字一仏経). Fragment X2010:1.8 is a fragment of fascicle 2, chapter 3 of the Lotus Sutra, titled “Simile and Parable.” It includes parts of five lines from the original copied sutra.

At first glance, the segment may appear strange in its distribution of characters. The first four lines of the fragment all begin with two characters at the top, with a two-character’s worth of spacing, then another two sets of five characters. However, the last line has seventeen characters generally evenly distributed, without any larger spacing between any of them.

Following a typical format of Buddhist scriptures, the Lotus Sutra summarizes each Buddha’s teaching explicated in prose in a five-character verse. The last line appears different from the first four because this fragment includes these two different narrative types. The first four lines of this fragment are the end portion of a verse, while the last line is the beginning of a new prose narrative.

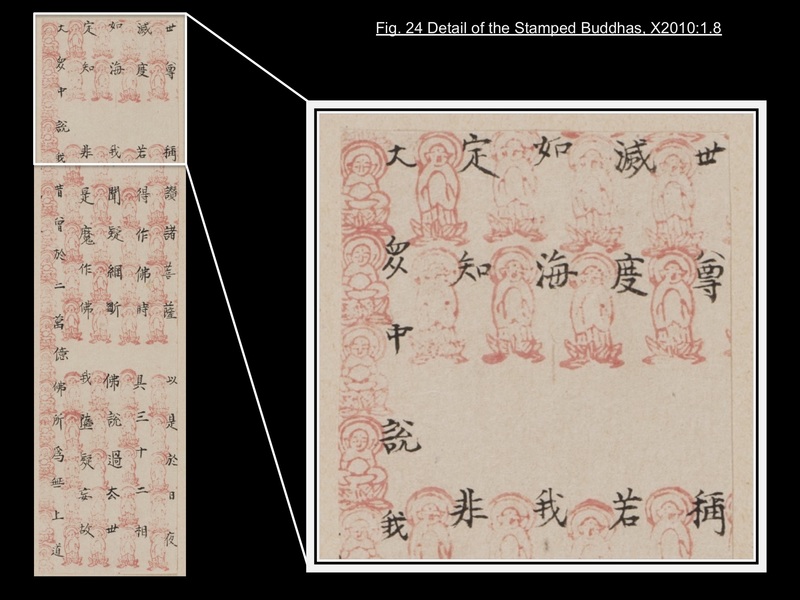

Each character in this copied sutra is accompanied by a little Buddha image stamped in red ink (Fig. 24, see image below). There is a mini Buddha standing on a lotus pedestal next to each character in the verse section of the sutra, while a mini seated Buddha accompanies each character in the prose section. Although the ink appears faint in places, we can see that an effort has been made so that the characters will align with the head of their accompanying mini Buddhas.

The fifth line shows that, at least in this fragmented section, there are seventeen characters in a line. The number of characters adheres to the convention of Japanese sutra copying that typically holds about seventeen or eighteen characters per line for the prose section.1 However, because the first verse of each of the first four lines only has two characters as opposed to the standard five, we can surmise that there were at least several more characters above these lines that are now cropped.

Exactly how much was cut out?

What you see in Figure 25 is the equivalent of the section that appears in the first two lines of the fragment, taken from the English translation by Burton Watson (Fig. 25, see image below).2 The lines highlighted in yellow are the only parts that we can see in this fragment, meaning everything after “then day and night” to “extinction” is cropped off either after the end of the current line one, and/or before the current line two – 67 characters in total.

Considering that this particular copy inserts two-character’s worth of spacing between each verse, the actual number of characters missing per line for the verse section is 103. The verse section is typically indented by a few characters compared to the prose section. Based on the number of estimated characters missing above and below the first line of the prose section (the fifth line on the fragment), we can estimate that the original had approximately 112 characters per line.

That is quite a bit of cropping. Looking at the edges of the fragment, we can surmise that an effort has been made to preserve all of the mini Buddha-stamps intact, even in this process of massive cropping. However, you can see from the English excerpt that as far as the content is concerned, the original teaching of the sutra is made completely incomprehensible in this fragment. So, there is no question that the function of this “sutra” was altered due to this fragmentation, from something to be read and studied, to something to be appreciated visually.

However, does this mean that the religious energy of the “sutra” as a sacred text is completely lost? This is actually an interesting theological question.

“One-character One-Buddha” is a particular method of copying sutras used for copying the Lotus Sutra. The JSMA fragment is a Momoyama-period work in the lineage of something like this example from Zentsûji. The scroll displays an image of a seated Buddha next to each character copied. This method of copying was used for the Lotus Sutra because it teaches that each word of this sutra is equivalent to the Buddha himself. A devotee who utters even a syllable from this sutra, or copies even one character, is accumulating great merit.

What is interesting is that the same idea is conveyed in other creative compositions. For instance, in this twelfth-century example by Monk Shinsai 心西 (fl. circa 12th century), each of the characters is enshrined within its own little pagoda. In other words, as far as the Lotus Sutra is concerned, the power is in the individual character, or a single utterance.

The natural implication of this is that the sutra as a whole is that much more powerful, since it strings together so many of these utterances. However, if each character is enshrined in its own pagoda, occupying an independent space, one could arguably say that the idea of fragmentation is inherent in this sutra and the spiritual power is not in the meaning but in the syllable. By this logic, the physical act of cutting the sutra cannot affect the religious potency of this copied sutra. Thus, the cutting of a copied Lotus Sutra is an act of destruction of the integrity of the sutra as an object, whether it be a scroll or a book, but it may be an act that actually underlines the magical power of the calligraphy.

1. For instance, in the JSMA set, all but five fragments follow this standard layout. ↩

2. Burton Watson trans., “Simile and Parable,” in The Lotus Sutra (NY: Columbia Univ. Press, 1993), 49-50. ↩